2 February 2015

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Can smoke from fires intensify tornadoes?

“Yes,” say researchers, who examined the effects of smoke –- resulting from spring agricultural land-clearing fires in Central America — transported across the Gulf of Mexico and encountering tornado conditions already in process in the United States.

The new study, accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, examined the smoke impacts on a historic severe weather outbreak that occurred during the afternoon and evening of April 27, 2011. The weather event produced 122 tornadoes, resulted in 313 deaths across the Southeastern United States and is considered the most severe event of its kind since 1950.

A tornado in Shoal Creek Valley Alabama during a historic severe weather outbreak on April 27, 2011. A new study finds that a severe weather outbreak in 2011 was caused mainly by environmental conditions leading to a large potential for tornado formation and conducive to supercells, and that smoke particles intensified these conditions.

Credit: Wjalex4/Wikimedia Commons

The outbreak was caused mainly by environmental conditions leading to a large potential for tornado formation and conducive to supercells, a type of thunderstorm. However, smoke particles intensified these conditions, according to co-authors Gregory Carmichael, professor of chemical and biochemical engineering at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, and Pablo Saide, Center for Global and Regional Environmental Research (CGRER) post-doctoral fellow at the University of Iowa.

They say the smoke lowered the base of the clouds and increased wind shear, defined as wind speed variations with respect to altitude. Together, those two conditions increased the likelihood of more severe tornadoes. The effects of smoke on these conditions had not been previously described, and the study found a novel mechanism to explain these interactions.

“These results are of great importance, as it is the first study to show smoke influence on tornado severity in a real case scenario. Also, severe weather prediction centers do not include atmospheric particles and their effects in their models, and we show that they should at least consider it,” says Carmichael.

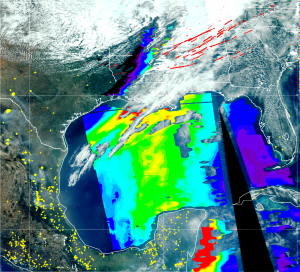

This image shows MODIS-Aqua satellite products for 27 April 2011 over the southeast US, Central America and the Gulf of Mexico (GoM), along with tornado tracks (red solid lines, thickness indicates the magnitude of the tornado reports , thickest=5, thinnest=1) for the period from April 26-28, 2011. The background is a true color image of the surface, clouds, and smoke, with yellow markers indicating fire detections and an iridescent overlay showing aerosol optical depth (AOD). Red, green and purple colors show high (1.0), medium (0.6) and low (0.1) AOD values. The article by Saide et al. (2015) shows that the increase in aerosol loads in the GoM is produced by fires in Central America, and this smoke is further transported to the southeast US where it can interact with clouds and radiation producing environmental conditions more favorable to significant tornado occurrence for the historical outbreak on 27 April 2011. Satellite L1B (true color image), AOD, and fire detection retrievals obtained from the NASA Level 1 and Atmosphere Archive and Distribution System (LAADS); Tornado reports obtained from the NOAA Storm Prediction Center (SPC); imagery courtesy of Brad Pierce NOAA Satellite and Information Service (NESDIS) Center for Satellite Applications and Research (STAR).

Credit: Pablo Saide

“We show the smoke influence for one tornado outbreak, so in the future we will analyze smoke effects for other outbreaks on the record to see if similar impacts are found and under which conditions they occur,” says Saide. “We also plan to work along with model developers and institutions in charge of forecasting to move forward in the implementation, testing and incorporation of these effects on operational weather prediction models.”

In order to make their findings, the researchers ran computer simulations based upon data recorded during the 2011 event. One type of simulation included smoke and its effect on solar radiation and clouds, while the other omitted smoke. In fact, the simulation including the smoke resulted in a lowered cloud base and greater wind shear.

Future studies will focus on gaining a better understanding of the impacts of smoke on near-storm environments and tornado occurrence, intensity and longevity, adds Carmichael, who also serves as director of the Iowa Informatics Initiative and co-director of CGRER.

The research was funded by grants from NASA, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, National Institutes of Health, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Fulbright-CONICYT scholarship program in Chile.

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 62,000 members in 144 countries. Join our conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social media channels.

Notes for Journalists

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of this article by clicking on this link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014GL062826/abstract?campaign=wlytk-41855.5282060185

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Nanci Bompey at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Central American biomass burning smoke can increase tornado severity in the U.S.”

Authors:

P. E. Saide: Center for Global and Regional Environmental Research (CGRER), University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA;

S. N. Spak: Center for Global and Regional Environmental Research (CGRER), University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA;

R. B. Pierce: NOAA Satellite and Information Service (NESDIS) Center for Satellite Applications and Research (STAR), Madison, Wisconsin, USA;

J. A. Otkin and T. K. Schaack: Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA;

A. K. Heidinger: NOAA Satellite and Information Service (NESDIS) Center for Satellite Applications and Research (STAR), Madison, Wisconsin, USA;

A. M. da Silva: Global Modeling and data Assimilation Office, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA;

M. Kacenelenbogen: BAER Institute/NASA Ames, Moffett Field, California, USA;

J. Redemann: NASA Ames, Moffett Field, California, USA;

G. R. Carmichael: Center for Global and Regional Environmental Research (CGRER), University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Contact information for the authors:

Pablo Saide: [email protected]

Greg Carmichael: +1 (319) 335-1414, [email protected]

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

[email protected]

University of Iowa Contact:

Gary Galluzzo

+1 (319) 384-0009

[email protected]