31 May 2017

Photo of the Colle Gnifetti glacier on the Swiss-Italian border where the ice core used in the study was taken. In the bottom right corner the coring site can be seen (white dome).

Credit: Nicole Spaulding, Climate Change Institute, University of Maine.

WASHINGTON, DC — A new study combining European ice core data and historical records of the infamous Black Death pandemic of 1349-1353 shows metal mining and smelting have polluted the environment for thousands of years, challenging the widespread belief that environmental pollution began with the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s and 1800s.

The new study, accepted for publication in GeoHealth, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, provides evidence that the natural level of lead in the air is essentially zero, contrary to common assumptions. The research shows lead pollution from mining and smelting was detectable well before the Industrial Revolution and only when the Black Death pandemic halted those activities did lead in the air return to natural levels.

“These new data show that human activity has polluted European air almost uninterruptedly for the last ca. 2000 years,” the study’s authors write. “Only a devastating collapse in population and economic activity caused by pandemic disease reduced atmospheric pollution to what can now more accurately be termed ‘background’ or natural levels.”

The new findings could affect the current standards for lead pollution. Current public health and environmental policy deem pre-industrial lead pollution levels to be “natural” and thus presumably “safe,” but this assumption may need to be re-examined, according to the study’s authors.

Lead is one of the most dangerous environmental pollutants and is toxic to the brain at extremely low levels. No levels of lead can be considered safe in children, according to Philip Landrigan, Dean of Global Health for the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, who was not connected to the new study.

“It’s clear that lead has lasting effects on children’s lives,” said Landrigan, who has researched lead poisoning in children and was instrumental in the implementation of abatement policies in past years.

The ice core from the Colle Gnifetti glacier within the drill as it’s being extracted.

Credit: Nicole Spaulding, Climate Change Institute, University of Maine.

Reconstructing past lead levels

In the new study, historians at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, collaborated with climate scientists at the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine in Orono. The team chose to examine past lead levels in the air because it is a dangerous pollutant and serves as a proxy for economic activity, ramping up when economies grow and tailing off when they decline.

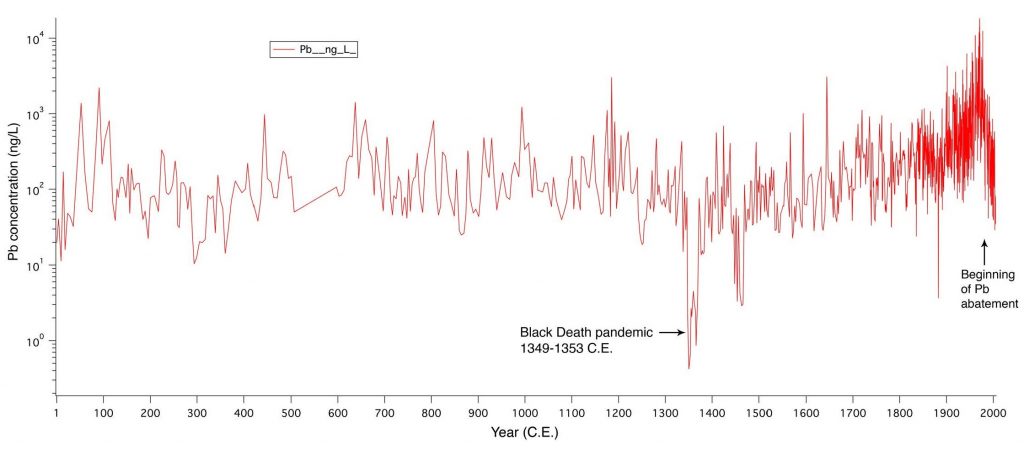

The researchers matched new, high-resolution measurements of lead in an ice core taken from a glacier in the Swiss/Italian Alps with highly detailed historical records showing that lead mining and smelting activity plummeted to nearly zero during the plague pandemic years of 1349 to 1353.

The researchers found that lead levels declined suddenly in a section of the ice core corresponding to that four-year window of time. That decline is unique in the last 2,000 years of European history, according to Alexander More, a historian at Harvard and lead author of the new study.

This graph shows lead concentrations in the atmosphere taken by measurements from the Colle Gnifetti ice core used in the study. The graph covers the period of circa 1 – 2007 C.E. The Black Death drop marks the years 1349-1353 C.E.

Credit: Alexander More/AGU/GeoHealth.

“When we saw the extent of the decline in lead levels, and only saw it once, during the years of the pandemic, we were intrigued,” More said. “In different parts of Europe, the Black Death wiped out as much as half of the population. It radically changed society in multiple ways. In terms of the labor force, the mining of lead essentially stopped in major areas of production. You see this reflected in the ice core in a large drop in atmospheric lead levels, and you see it in historical records for an extended period of time.”

Some of the historical records the study authors consulted to create a historical database of climate reports published with the article. They contain legal, tax and commercial evidence documenting climate changes through eyewitness reports. These records provide evidence of the arrival of the Black Death in Europe as well as evidence of the decline of mining because of it.

Credit: Alexander More, Harvard University and Climate Change Institute, University of Maine.

The researchers also found other, lesser, drops in lead accumulation in the ice core. One occurred in 1460, which the authors show may have also been due to an epidemic-related downturn. Other drops occurred during an economic slowdown in 1885 and most recently in the 1970s when abatement policies phased out leaded gasoline and other sources of lead air pollution.

More said the ice core holds much additional data, accessible due to the precision of the Climate Change Institute’s next generation laser facility and the expertise of climate scientists on the research team. Combining that data with historical sources can lead to new discoveries in the fields of climate science, the history of human and planetary health, environmental and economic history, he said.

“This research represents the convergence of two very different disciplines, history and ice core glaciology, that together provide the perspective needed to understand how a toxic substance like lead has varied in the atmosphere and, more importantly, to understand that the true natural level is in fact very close to zero,” said Paul Mayewski, Director of the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine and co-author of the new study. “Using the ultra-high resolution ice core sampling offered through our W. M. Keck Laser Ice Facility, we expect to be able to offer new insights, previously unattainable with lower-resolution sampling, into the links between climate change and the course of civilization.”

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing 60,000 members in 137 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

Notes for Journalists

This research article is open access. A PDF copy of the article can be downloaded at the following link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2017GH000064/pdf

Journalists and PIOs may also order a copy of the final paper by emailing a request to Lauren Lipuma at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Next generation ice core technology reveals true minimum natural levels of lead (Pb) in the atmosphere: insights from the Black Death”

Authors:

Alexander F. More: Initiative for the Science of the Human Past and Department of History, Harvard University, Cambridge, Masssachusetts, U.S.A. and Climate Change Institute, Sawyer Environmental Research Building, University of Maine, Orono, Maine, U.S.A.;

Michael McCormick: Initiative for the Science of the Human Past and Department of History, Harvard University, Cambridge, Masssachusetts, U.S.A.;

Nicole E. Spaulding, Michael J. Handley, Elena V. Korotkikh, Andrei V. Kurbatov, Sharon B. Sneed, Paul. A. Mayewski: Climate Change Institute, Sawyer Environmental Research Building, University of Maine, Orono, Maine, U.S.A.;

Pascal Bohleber: Climate Change Institute, Sawyer Environmental Research Building, University of Maine, Orono, Maine, U.S.A. and Institute of Environmental Physics, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany;

Helene Hoffmann: Institute of Environmental Physics, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany;

Christopher P. Loveluck: Department of Archaeology, University Park, School of Humanities, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, United Kingdom.

Contact information for the authors:

Alexander F. More: [email protected],

Lauren Lipuma

+1 (202) 777-7396

[email protected]