Scientists compile densest carbon data set in Antarctic waters

10 September 2015

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Since 2002, the Southern Ocean has been removing more of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, according to two new studies.

The ARSV Laurence M. Gould, which supports research funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) in the Antarctic, makes nearly 20 crossings of the Drake Passage each year.

Credit: Colm Sweeney/ CIRES & NOAA

These studies make use of millions of ship-based observations and a variety of data analysis techniques to conclude that that the Southern Ocean has increasingly taken up more carbon dioxide during the last 13 years. That follows a decade from the early 1990s to 2000s, where evidence suggested the Southern Ocean carbon dioxide sink was weakening. The new studies appear today in the American Geophysical Union journal Geophysical Research Letters and the AAAS journal Science.

The global oceans are an important sink for human-released carbon dioxide, absorbing nearly a quarter of the total carbon dioxide emissions every year. Of all ocean regions, the Southern Ocean below the 35th parallel south plays a particularly vital role. “Although it comprises only 26 percent of the total ocean area, the Southern Ocean has absorbed nearly 40 percent of all anthropogenic carbon dioxide taken up by the global oceans up to the present,” says David Munro, a scientist at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) at the University of Colorado Boulder, and an author on the GRL paper.

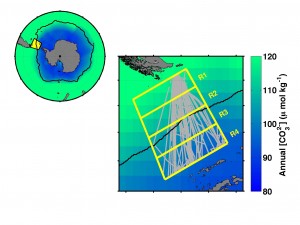

Figure 1. Above left is a map of the Southern Ocean with the Drake Passage study region in yellow. Above right is the Drake Passage, with study regions R1–R4 marked and the Antarctic Polar Front outlined in black. The gray lines show nearly 250 transects of the ARSV Laurence M. Gould where carbon measurements were made from 2002–2015. The maps also show the annual concentration of carbonate ion, with lowest concentrations closest to the Antarctic continent.

The GRL paper focuses on one region of the Southern Ocean extending from the tip of South America to the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula (see Figure 1). “The Drake Passage is the windiest, roughest part of the Southern Ocean,” says Colm Sweeney, lead investigator on the Drake Passage study, co-author on both the GRL and Science papers, and a CIRES scientist working in the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado. “The critical element to this study is that we were able to sustain measurements in this harsh environment as long as we have—both in the summer and the winter, in every year over the last 13 years. This data set of ocean carbon measurements is the densest ongoing time series in the Southern Ocean.”

The team was able to take these long-term measurements by piggybacking instruments on the Antarctic Research Supply Vessel Laurence M. Gould. The National Science Foundation-supported Gould, which makes nearly 20 crossings of the Drake Passage each year, transporting people and supplies to and from Antarctic research stations. For over 13 years, it’s taken chemical measurements of the atmosphere and surface ocean along the way.

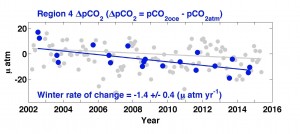

Figure 2. This figure shows the time series trend in ΔpCO2 (gray) for Region 4 south of the Antarctic Polar Front, with winter observations and trend in blue. The ΔpCO2 is the difference between the partial pressures of CO2 in the ocean and the overlying atmosphere. A decline in ΔpCO2 corresponds to an increase in ocean CO2 uptake.

By analyzing more than one million surface ocean observations, the researchers could tease out subtle differences between the carbon dioxide trends in the surface ocean and the atmosphere that suggest a strengthening of the carbon sink. This change is most pronounced in the southern half of the Drake Passage during winter (see Figure 2). Although the researchers aren’t sure of the exact mechanism driving these changes, “it’s likely that winter mixing with deep waters that have not had contact with the atmosphere for several hundred years plays an important role,” says Munro.

The Science paper, led by Peter Landschützer at the ETH Zurich, takes a more expansive view of the Southern Ocean. This study uses two innovative methods to analyze a dataset of surface water carbon dioxide spanning almost three decades and covering all of the waters below the 35th parallel south. These data—including Sweeney and Munro’s data from the Drake Passage—also show that the surface water carbon dioxide is increasing slower than atmospheric carbon dioxide, a sign that the Southern Ocean as a whole is more efficiently removing carbon from the atmosphere. These results follow previous findings that showed that the Southern Ocean carbon dioxide sink was stagnant or weakening from the early 1990s to the early 2000s.

In addition to the Drake Passage measurements, the Science paper uses datasets that represent a significant international collaboration, including carbon dioxide sampling from NOAA’s Ship of Opportunity Program. This program, led by Rik Wanninkhof of NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) who is also a coauthor of the Science paper, is the world’s largest coordinated ocean carbon dioxide sampling operation. Despite all these efforts, the Southern Ocean remains undersampled. “Given the importance of the Southern Ocean to the global oceans’ role in absorbing atmospheric carbon dioxide, these studies suggest that we must continue to expand our measurements in this part of the world despite the challenging environment,” says Sweeney.

This study was funded primarily by the NSF and NOAA’s Climate Program Office.

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 60,000 members in 139 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

CIRES is a partnership of NOAA and CU-Boulder.

Notes for Journalists

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of the GRL article by clicking on this link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2015GL065194/abstract?campaign=wlytk-41855.5282060185

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Nanci Bompey at [email protected].

Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the GRL paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Recent evidence for a strengthening CO2 sink in the Southern Ocean from carbonate system measurements in the Drake Passage (2002-2015)”

Authors:

David Munro: Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) and the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences (ATOC), University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA;

Nicole Lovenduski: Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) and the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences (ATOC), University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA;

Taro Takahashi: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA;

Britton Stephens: National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado, USA;

Timothy Newberger: Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) and NOAA, Boulder, Colorado, USA;

Colm Sweeney: CIRES and NOAA ESRL Global Monitoring Division, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Contact Information for the Authors:

Colm Sweeney: +1 (303) 497-4771, [email protected]

David Munro: +1 (303) 735-6582, [email protected]

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

[email protected]

CIRES Contact:

Karin Vergoth

+1 (303) 497-5125

[email protected]