27 August 2014

WASHINGTON, D.C. – In the unlikely event of a volcanic supereruption at Yellowstone National Park, the northern Rocky Mountains would be blanketed in meters of ash, and millimeters would be deposited as far away as New York City, Los Angeles and Miami, according to a new study.

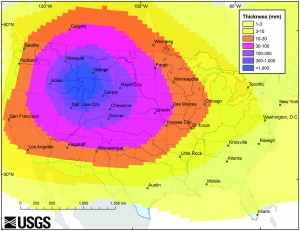

An example of the possible distribution of ash from a month-long Yellowstone supereruption. The distribution map was generated by a new model developed by the U.S. Geological Survey using wind information from January 2001. The improved computer model, detailed in a new study published in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, finds that the hypothetical, large eruption would create a distinctive kind of ash cloud known as an umbrella, which expands evenly in all directions, sending ash across North America. Ash distribution will vary depending on cloud height, eruption duration, diameter of volcanic particles in the cloud, and wind conditions, according to the new study.

Credit: USGS

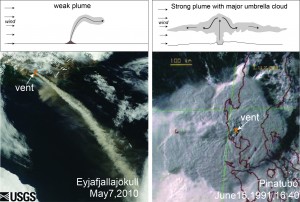

An improved computer model developed by the study’s authors finds that the hypothetical, large eruption would create a distinctive kind of ash cloud known as an umbrella, which expands evenly in all directions, sending ash across North America.

A supereruption is the largest class of volcanic eruption, during which more than 1,000 cubic kilometers (240 cubic miles) of material is ejected. If such a supereruption were to occur, which is extremely unlikely, it could shut down electronic communications and air travel throughout the continent, and alter the climate, the study notes.

A giant underground reservoir of hot and partly molten rock feeds the volcano at Yellowstone National Park. It has produced three huge eruptions about 2.1 million, 1.3 million and 640,000 years ago. Geological activity at Yellowstone shows no signs that volcanic eruptions, large or small, will occur in the near future. The most recent volcanic activity at Yellowstone—a relatively non-explosive lava flow at the Pitchstone Plateau in the southern section of the park—occurred 70,000 years ago.

Researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey used a hypothetical Yellowstone supereruption as a case study to run their new model that calculates ash distribution for eruptions of all sizes. The model, Ash3D, incorporates data on historical wind patterns to calculate the thickness of ash fall for a supereruption like the one that occurred at Yellowstone 640,000 years ago.

The new study provides the first quantitative estimates of the thickness and distribution of ash in cities around the U.S. if the Yellowstone volcanic system were to experience this type of huge, yet unlikely, eruption.

Cities close to the modeled Yellowstone supereruption could be covered by more than a meter (a few feet) of ash. There would be centimeters (a few inches) of ash in the Midwest, while cities on both coasts would see millimeters (a fraction of an inch) of accumulation, according to the new study that was published online today in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, a journal of the American Geophysical Union. The paper has been made available at no charge at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014GC005469/abstract.

The figure above shows illustrations of plume shapes that would result from different types of volcanic eruptions. A weak plume (left) typically forms above small eruptions such as the April-May 2010 eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland, as shown in this NASA Earth Observatory image. A strong plume with a major umbrella cloud (right) forms during very large eruptions, such as shown in this Japanese Meteorological Agency image of the Pinatubo cloud on June 15, 1991. During superuruptions, umbrella clouds from strong plumes may push their way hundreds or thousands of kilometers upwind, according to a new study published in Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems.

Credit: USGS

The model results help scientists understand the extremely widespread distribution of ash deposits from previous large eruptions at Yellowstone. Other USGS scientists are using the Ash3D model to forecast possible ash hazards at currently restless volcanoes in Alaska.

Unlike smaller eruptions, whose ash deposition looks roughly like a fan when viewed from above, the spreading umbrella cloud from a supereruption deposits ash in a pattern more like a bull’s eye – heavy in the center and diminishing in all directions – and is less affected by prevailing winds, according to the new model.

“In essence, the eruption makes its own winds that can overcome the prevailing westerlies, which normally dominate weather patterns in the United States,” said Larry Mastin, a geologist at the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Washington, and the lead author of the new paper. Westerly winds blow from the west.

“This helps explain the distribution from large Yellowstone eruptions of the past, where considerable amounts of ash reached the west coast,” he added.

The three large past eruptions at Yellowstone sent ash over many tens of thousands of square kilometers (thousands of square miles). Ash deposits from these eruptions have been found throughout the central and western United States and Canada.

Erosion has made it difficult for scientists to accurately estimate ash distribution from these deposits. Previous computer models also lacked the ability to accurately determine how the ash would be transported.

Using their new model, the study’s authors found that during very large volcanic eruptions, the expansion rate of the ash cloud’s leading edge can exceed the average ambient wind speed for hours or days depending on the length of the eruption. This outward expansion is capable of driving ash more than 1,500 kilometers (932 miles) upwind – westward — and crosswind – north to south — producing a bull’s eye-like pattern centered on the eruption site.

In the simulated modern-day eruption scenario, cities within 500 kilometers (311 miles) of Yellowstone like Billings, Montana, and Casper, Wyoming, would be covered by centimeters (inches) to more than a meter (more than three feet) of ash. Upper Midwestern cities, like Minneapolis, Minnesota, and Des Moines, Iowa, would receive centimeters (inches), and those on the East and Gulf coasts, like New York and Washington, D.C. would receive millimeters or less (fractions of an inch). California cities would receive millimeters to centimeters (less than an inch to less than two inches) of ash while Pacific Northwest cities like Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington, would receive up to a few centimeters (more than an inch).

An aerial flight over Yellowstone’s Midway Geyser Basin in 2004 shows Grand Prismatic Spring and Excelsior Geyser Crater, which drain into the nearby Firehole River.

Credit: USGS

Even small accumulations only millimeters or centimeters (less than an inch to an inch) thick could cause major effects around the country, including reduced traction on roads, shorted-out electrical transformers and respiratory problems, according to previous research cited in the new study. Prior research has also found that multiple inches of ash can damage buildings, block sewer and water lines, and disrupt livestock and crop production, the study notes.

The study also found that other eruptions – powerful but much smaller than a Yellowstone supereruption — might also generate an umbrella cloud.

“These model developments have greatly enhanced our ability to anticipate possible effects from both large and small eruptions, wherever they occur,” said Jacob Lowenstern, USGS Scientist-in-Charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory in Menlo Park, California, and a co-author on the new paper.

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 62,000 members in 144 countries. Join our conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social media channels.

Notes for Journalists

A PDF copy of this article can be downloaded at no cost by clicking on this link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014GC005469/abstract.

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Nanci Bompey at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Modeling ash fall distribution from a Yellowstone supereruption”

Authors:

Larry G. Mastin: U.S. Geological Survey, Cascades Volcano Observatory, Vancouver, WA, USA;

Alexa R. Van Eaton: U.S. Geological Survey, Cascades Volcano Observatory, Vancouver, WA, USA; and School of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona, USA;

Jacob B. Lowenstern: U.S. Geological Survey, Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, Menlo Park, CA, USA.

Contact information for the authors:

Larry G. Mastin: +1 (360) 993-8925, [email protected]

Jacob B. Lowenstern: +1 (650) 329-5238, [email protected]

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

[email protected]