Frequent high-pressure weather systems centered over Greenland push away fresh snowfall, leaving larger, older snow grains on the surface that make the ice sheet less reflective

17 May 2021

Researcher Gabriel Lewis measures reflectivity on Greenland’s ice sheet during a 2016 research expedition. A reduction in fresh snowfall has caused parts of Greenland to become darker and may lead to additional surface melt, according to a new study.

Credit: Forrest McCarthy

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, [email protected] (UTC-4 hours)

Dartmouth press contact:

David Hirsch, +1 (603) 646-9130, [email protected], (UTC-4 hours)

Contact information for the researchers:

Gabe Lewis, Dartmouth College, [email protected], (UTC-4 hours)

Erich Osterberg, Dartmouth College, [email protected], (UTC-4 hours)

WASHINGTON—A lack of fresh snow is darkening Greenland’s surface, likely contributing to faster melting. The snow shortfall is a consequence of a persistent weather system that blocks precipitation and warms temperatures over the icesheet interior, a new study finds.

The Greenland Ice Sheet has warmed 2.7 degrees Celsius (4.85 degrees Fahrenheit) since 1982. It is experiencing the greatest melt and runoff rates in at least the last 450 years, and likely the greatest rates in the last 7,000 years, according to the authors of the new study, published today in Geophysical Research Letters, AGU’s journal for high-impact, short-format reports with immediate implications spanning all Earth and space sciences.

Dimming surface albedo, or reflectivity, has the potential to accelerate this process further. Darker snow and ice absorb more heat from the sun, which may lead to faster sea level rise than expected, the authors say.

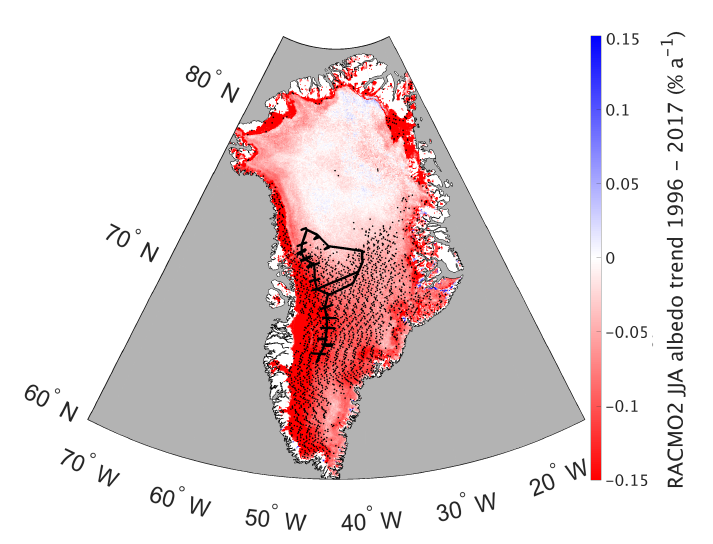

Change in surface albedo (reflectivity) across Greenland’s ice sheet from 1996 to 2017. A greater decline in albedo is indicated in dark red. The research team’s data collection route is noted by the black line. From figure 3 of the new study.

Credit: AGU

Data from NASA’s MODIS satellite show Greenland reflecting less light over the last two decades. The new study finds surface contamination by soot, dust or microorganisms cannot account for the observed changes. Instead, the authors found the changing shape of snowflakes under sunlight is the likely darkening agent. As changing weather patterns bring less fresh snow to Greenland, aging snow grains on the surface grow larger and less reflective.

“When you have fresh snowfall and the sun comes out, it is blinding, you can’t walk outside without sunglasses, but give it a day or two and that same snow is no longer as reflective, right? As snow ages, even over hours to a few days, you get this change in albedo, and that’s why the fresh snow is so important,” said Erich Osterberg, a climate scientist at Dartmouth College and leader of the new study.

Measuring snow in Greenland’s Goldilocks zone

The team gathered on-the-ice data during a two-summer, 4,400-kilometer (2,700-mile) snowmobile trek across an important mid-elevation region of the ice sheet scientists call the western percolation zone. In this area, the surface warms enough to melt on 10-20 summer days each year, but on average more snow falls than melts or evaporates. This critical balance has been changing rapidly in recent decades, the authors say.

Sitting well above the most-studied areas on Greenland’s southwestern coast, where the ice is actively melting away, and below the cold ice sheet summit, where research stations record data year-round, this key middle region had not been visited by scientists since the 1990s, just before a major turning point that saw human-caused climate change drive accelerated melting across Greenland.

“We found the amount of impurities in the snow is about 1 part per billion, so it’s some of the cleanest snow in the world,” said Gabriel Lewis, a researcher at Dartmouth College and the first author of the new study. “Using computer models, we can calculate how that would change the albedo of the surface. In our research area, it does not appear to be enough to account for the change in albedo other research teams have reported.”

A less shiny snowflake

Lewis and his colleagues also measured individual snow grains in the snowpack across the percolation zone, finding the increased size since the 1990s could explain the observed changes in reflectivity.

As the delicate points of the fresh snowflakes melt or evaporate, they round over into blobs that absorb more sunlight instead of reflecting it off the crystal facets. This makes the snow surface darker. The difference is too small to see with the naked eye on the incredibly bright surface of the ice sheet, but a 1% change in reflectivity could cause 25 additional gigatons of ice to be lost in a three-year period, the authors calculated.

“Fresh snow looks like what you would draw in a kindergarten class or cut from a piece of paper—it’s got all these really nice points, and that’s because it’s extremely cold in the atmosphere when it falls,” Lewis said. “Once it falls and sits on the surface of the icesheet in the sun, it metamorphoses and the snow grains become larger over time.”

Storms that deposit new snow, the study found, are coming less often.

Atmospheric triple whammy

In the mid-nineties, a weather pattern called atmospheric blocking increased dramatically in frequency and duration over Greenland. The pattern is so influential to weather in the Northern Hemisphere, meteorologists track it as the Greenland Blocking Index. Researchers don’t understand why atmospheric blocking has reached record levels in recent decades, or how human caused climate change has influenced these shifting weather patterns.

These high-pressure systems sit over the center of the icesheet for days to weeks, blocking other weather systems from passing through. Snowstorms get pushed to the north, so fresh, high-albedo snow does not replenish the Greenland Ice Sheet surface as much or as often, according to the new study.

The blocking system also holds warmer air over Western Greenland, raising temperatures, the research team reported previously, and fewer clouds mean more sunlight reaches the surface.

“It’s like a triple whammy effect,” Osterberg said. “Not only does blocking raise temperatures, but it makes the icesheet darker by having less snowfall and by having fewer clouds. This all contributes to Greenland melting faster and faster.”

###

AGU (www.agu.org) supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists:

This research study will be freely available for 30 days. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

“Atmospheric Blocking Drives Recent Albedo Change Across the Western Greenland Ice Sheet Percolation Zone”

Authors:

- Gabriel Lewis, corresponding author (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire; and University of Nevada Reno, USA)

- Erich Osterberg (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA)

- Robert Hawley (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA)

- Hans-Peter Marshall (Boise State University, Idaho, USA)

- Tate Meehan (Boise State University, Idaho, USA)

- Karina Graeter (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA)

- Forrest McCarthy (University of Alaska Fairbanks)

- Thomas Overly (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA; and University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA)

- Zayta Thundercloud (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA)

- David Ferris (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, USA)

- Bess Koffman (Colby College, Waterville, Maine, USA)

- Jack Dibb (University of New Hampshire, Durham, New Hampshire, USA)