Global warming conjures up images of drought and fires in the minds of many, but a new study finds most communities will encounter heavy rainfall, excessive heat and their combined repercussions.

14 September 2023

Co-occurring precipitation and heat extremes will become more frequent, severe and widespread under climate change, more so than dry and hot conditions, according to a new study published in the AGU journal Earth’s Future. Credit: Phillip Flores/Unsplash

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, [email protected] (UTC-4 hours)

Contact information for the researchers:

Xiaoling Su, Northwest A&F University, [email protected] (UTC+8 hours)

WASHINGTON — Earth’s land masses have a higher chance of becoming wetter than drier as temperatures rise. In a new study, researchers found that co-occurring precipitation and heat extremes will become more frequent, severe and widespread under climate change, more so than dry and hot conditions.

When wet-hot conditions strike, heat waves first dry out the soil and reduce its ability to absorb water. Subsequent rainfall has a harder time penetrating the soil and instead runs along the surface, contributing to flooding, landslides and crop failures.

“These compound climate extremes have attracted considerable attention in recent decades due to their disproportionate pressures on the agricultural, industrial and ecosystems sectors — much more than individual extreme events alone,” said Haijiang Wu, a researcher at China’s Northwest A&F University and the lead author of the study. The research was published in Earth’s Future, AGU’s journal for interdisciplinary research on the past, present and future of our planet and its inhabitants.

The team used a series of climate models to project compound climate extremes by the end of the century if carbon dioxide emissions continue to rise.

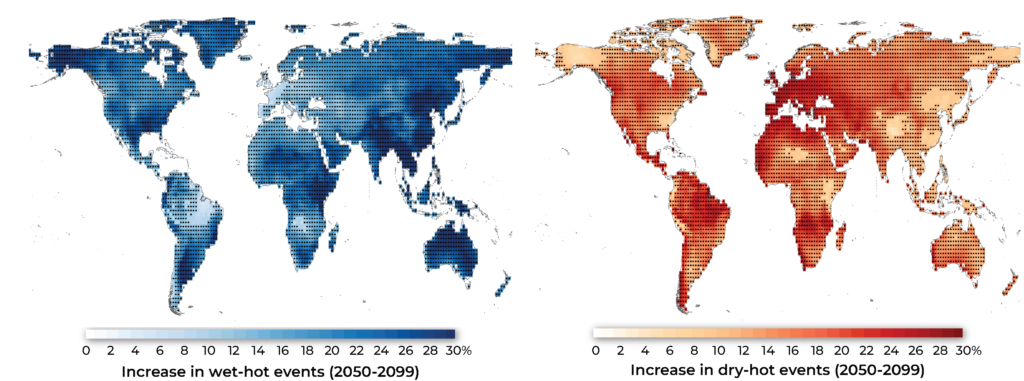

They found that while some regions of the world will become drier as temperatures rise — such as South Africa, the Amazon and parts of Europe — many regions, including the eastern United States, eastern and southern Asia, Australia and central Africa will receive more precipitation. Wet-hot extremes will also cover a larger area and be more severe than dry-hot extremes.

Many regions will experience an increase in wet-hot extreme weather. Credit: AGU modified from Su et al. (2023)

In the future, wet-hot extremes will become more likely because the atmosphere’s capacity to hold moisture increases by 6% to 7% for every 1 degree Celsius rise in temperature. As Earth gets hotter, the warmer atmosphere will hold more water vapor, meaning more water will be available to fall as precipitation.

The regions likely to be hit hard by wet-hot extremes host many heavily populated areas that are already prone to geologic hazards, such as landslides and mudflows, and produce many of the world’s crops. An increase in severe rainfall and heatwaves could cause more landslides that threaten local infrastructure, while floods and extreme heat could destroy crops.

Many parts of the world are already experiencing wet-hot extremes. In western Europe, climatic conditions led to deadly flooding in 2021. That summer, record high temperatures dried out the soil. Soon after, heavy rainfall poured across the parched soil’s surface and triggered massive landslides and flash floods that washed away entire houses, claiming more than 200 lives.

The increase in wet-hot extremes, like the conditions of the European floods of 2021, creates a need for climate adaptation approaches that take wet-hot conditions into consideration.

“Given the fact that the risk of compound wet-hot extremes in a warming climate is larger than compound dry-hot extremes, these wet-hot extremes should be included in risk management strategies,” Wu said.

While heat waves and heavy rainfall can be dangerous on their own, their combined impacts can be even more devastating. “If we overlook the risk of compound wet-hot extremes and fail to take sufficient early warning, the impacts on water-food-energy security would be unimaginable,” Wu said.

Regional variation in how compound hot-wet and hot-dry events will change by 2050-2099. (Su et al./AGU)

###

Notes for Journalists:

This study is published in Earth’s Future, a fully open-access journal. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo. View and download a pdf of this study here.

Paper title:

“Increasing Risks of Future Compound Climate Extremes With Warming Over Global Land Masses”

Authors:

- Xiaoling Su, (corresponding author), Key Laboratory of Agricultural Soil and Water Engineering in Arid and Semiarid Areas, Ministry of Education, Northwest A&F University; College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering, Northwest A&F University

- Haijiang Wu, Key Laboratory of Agricultural Soil and Water Engineering in Arid and Semiarid Areas, Ministry of Education, Northwest A&F University; College of Water Resources and Architectural Engineering, Northwest A&F University

- Vijay P. Singh, Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, Texas A&M University; Zachry Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Texas A&M University; National Water and Energy Center, UAE University

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

#

Contributed by Gabriella Lewis