16 February 2016

WASHINGTON, DC — Existing GPS instruments at monitoring stations worldwide could be used to increase the speed and accuracy of tsunami warnings, according to a new study accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union. Real-time Global Positioning System (GPS) measurements can be used to show how major earthquakes displace the ocean floor, cutting tsunami warning times by nearly 20 minutes and potentially reducing harm to coastal communities, according to the study’s authors.

An example of a scientific GPS instrument used at monitoring stations. The instrument is perfectly mounted to the ground, and can measure motions as small as half an inch, or the size of a quarter. By contrast, phone GPS can only approximate your location within a meter (or a few feet) of your exact location. Photo taken in Chile.

Credit: Sebastian Riquelme

Tsunamis that originate from earthquakes near the shore are relatively rare. But these tsunamis are especially dangerous because they can arrive at the coastline within minutes. For coastal communities, quick and accurate warnings are essential for saving as many lives as possible, according to previous research.

Current systems use seismic instruments to detect the earthquake’s vibrations and issue tsunami warnings within five to 10 minutes after the quake ends. But these warnings cannot give specific information about the size and reach of the wave. It can take more than 20 minutes to obtain information about the exact strength and reach of the resulting tsunami.

The new study finds that real-time GPS data gathered at hundreds of geophysical monitoring stations around the world can be used to estimate how an earthquake deforms the sea floor. Warning agencies can use that information to determine the resulting tsunami strength for vulnerable coastal areas within two to three minutes. Earlier warnings for coastal communities could potentially save lives, said the study’s authors.

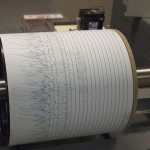

Maps B and C show Seismic and GPS stations reporting to public archives

(UNAVCO and IRIS) in 2000 (B) and in 2015 (C). These stations are representative of the worldwide growth and distribution of geophysical instruments but are not the total number of available stations.

Credit: Melgar, et al.

“This isn’t a deployment of new instruments, just a change in thinking and using these instruments,” said Diego Melgar, a research scientist at Berkeley Seismological Laboratory in Berkeley, California, and lead author of the new study. “Our results show that with what people have now, at geophysical monitoring agencies everywhere in the world, people can do this.”

Traditional tsunami warning systems

Current tsunami warning systems use seismometers, instruments that measure how the earth shakes during an earthquake, to pinpoint the epicenter, magnitude, and depth of an earthquake. Since the strength of a tsunami is not always directly related to the magnitude of the quake producing it, the additional information that real-time GPS data can quickly and accurately provide on the earthquake’s source is important.

A seismograph shows the aftermath of an earthquake, at Weston Observatory

Credit: Z22 – via Wikimedia Commons

Triangulating the source of an earthquake using seismometers.

Credit: USGS

As an earthquake increases in size, above 7.5 to 8 MW, its recorded magnitude becomes less reliable: seismometers closest to high-magnitude quakes often inaccurately record their size. Generating an accurate tsunami warning requires that warning agencies wait for the earthquake’s energy waves to reach earthquake monitoring stations farther away to generate an accurate model of the earthquake and resulting tsunami: a delay of up to 20 to 30 minutes after the first record of the earthquake, Melgar said.

The tsunami warnings generated after the Tohuku, Japan, earthquake in 2011 were generated using this method. The resulting tsunami, infamous for causing the Fukushima power plant meltdown, caused more than 15,000 deaths. Although the Japanese Meteorological Agency issued a tsunami warning three minutes after the quake, their initial estimate of the quake’s magnitude at 7.9 was too low and the tsunami warning it generated was too conservative. The quake was actually 30 times stronger with a magnitude of 9.0, according to previous research. Tsunami wave heights reached up to 128 feet (30 meters) above sea level, and swept inland as far as 6 miles (10 kilometers) in some areas

A newer, better method

Seismic monitoring stations around the world already use GPS to precisely monitor tectonic plate movements and determine how earthquakes change the landscape. The new study suggests existing GPS instruments can also be used to more quickly and accurately predict the size of an incoming tsunami.

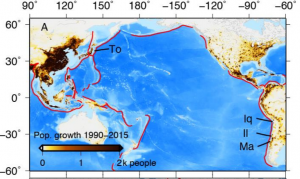

The red lines indicate subduction zones. The four earthquakes analyzed in this study are labeled: the 2010 Maule, Chile (Ma), 2011 Tohoku-oki, Japan (To), 2014 Iquique, Chile (Iq) and 2015 Illapel, Chile (Il) quakes. Population density in tsunami-prone areas has steadily increased over the last 25 years – making it more difficult to quickly evacuate these communities.

Credit: Melgar et al

To determine the accuracy of these GPS warnings, the researchers examined four recent tsunami-generating earthquakes. They examined records of the earthquake source, tsunami propagation, and tsunami inundation for each event. The researchers found that their system could generate more accurate tsunami warnings faster than existing warning systems. Using this system, tsunami warning maps could be generated within one to two minutes after the beginning of the earthquake. Information about the estimated height of tsunami waves took less than two additional minutes of time to compute.

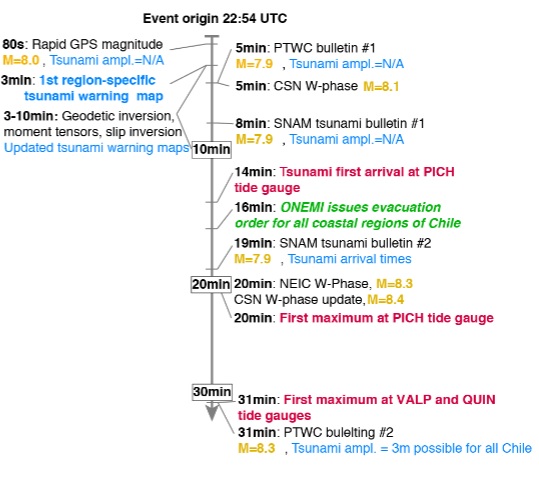

Timeline comparing the actual tsunami warnings created by different agencies using seismic data for the 2015 magnitude 8.3 Mw Illapel earthquake, and the response time and tsunami warnings that could have been issued using GPS.

Credit: Melgar, et al.

NOAA is in the process of incorporating this real-time GPS data into their existing tsunami and earthquake warning system, according to Barry Hirshorn, a senior geophysicist at NOAA’s Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) at the Inouye Regional Center (IRC), on Ford Island, Hawaii, who was not involved in the new study.

Currently, the PTWC can accurately estimate an earthquake’s magnitude up to 7.5 – 8. This magnitude estimate can usually be issued within two to four minutes after the beginning of the earthquake. According to Hirschhorn, GPS would enable more accurate magnitude estimates for earthquakes of a magnitude 8 and larger and provide additional information about the deformation of the seafloor within the same time frame. As over 90% of a tsunami’s casualties occur at the local or regional level, tsunami warning centers could save many lives by incorporating real-time GPS into their analysis, Hirshorn said.

The goal is to create a local tsunami warning system incorporating this technology for the entire West Coast of the U.S., Melgar said.

Hirshorn said the new paper provides a template for how to incorporate GPS data into tsunami operations. “We’ll be able to issue faster and more accurate tsunami warnings – and have a better idea of the true magnitude of M8 plus earthquakes much more rapidly – in some cases even before the earthquake is over,” he said.

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 60,000 members in 139 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

*****

Notes for Journalists

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of the article by clicking on this link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2015GL067100/full

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Lillian Steenblik Hwang at [email protected].

Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Local tsunami warnings: Perspectives from recent large events”

Authors:

Diego Melgar, Richard M. Allen:

University of California Berkeley, Seismological Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA

Sebastian Riquelme, Juan Carlos Baez, Sergio Barrientos:

Centro Sismológico Nacional, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile

Jianghui Geng:

Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

GNSS Center, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China

Francisco Bravo:

Universidad de Chile, Departamento de Geofísica, Santiago, Chile

Hector Parra:

Instituto Geográfico Militar, Santiago, Chile

Peng Fang, Yehuda Bock:

Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, USA

Michael Bevis:

The Ohio State University, School of Earth Sciences, Columbus, OH, USA

Dana J. Caccamise II:

The Ohio State University, School of Earth Sciences, Columbus, OH, USA

Now at the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, National Geodetic Survey, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Marcos Moreno:

Helmholz Centre, GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Potsdam, Germany

Robert Smalley Jr.:

CERI, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN, USA

Contact Information for the Authors:

Diego Melgar:

+1 (619) 734-8760

[email protected]

Lillian Steenblik Hwang

+1 (202) 777-7396

[email protected]