Unexpected wild bird species, from pelicans to peregrine falcons, are transporting the virus from poultry to new places around the world and changing where the risk of outbreaks is highest

25 March 2025

Wild migratory birds, from pelicans to peregrine falcons, carried bird flu from Asia to Europe, then on to Africa and the Americas, a new GeoHealth study reveals. The birds’ growing role of vectors, not only victims, could help explain why poultry culls have been largely ineffective for quashing the ongoing H5N1 outbreak. Credit: Gareth Davies/unsplash

Researcher contacts:

Samsung Lim, University of New South Wales, [email protected] (UTC+11 hours)

Raina MacIntyre, University of New South Wales, [email protected] (UTC+11 hours)

AGU press contact:

Rebecca Dzombak, [email protected] (UTC-4 hours)

WASHINGTON — Bird flu cases are rising rapidly in the United States and around the world. A new study traces how the disease spread over the last two decades from Asia to Europe, Africa and the Americas. New bird species, from pelicans to peregrine falcons, are catching and carrying the disease, the study finds. The pattern may be a clue to why culling domestic birds has not halted the most recent outbreak.

The study shows the important role a wider range of wild birds have as both victims and vectors of disease spread, upending previous assumptions about which birds spread the virus. The findings point to a need to revise how we monitor and treat avian influenza in birds, wild and domestic, to best protect human health.

Today, the biggest hotspots of avian influenza are in Europe and the Americas, rather than southeast Asia as it was in the 1990s, the study finds. But it’s not only the location that’s different; the disease’s temporal pattern is different, too.

“We know H5N1 has the potential to become a human pandemic, and the risk of that happening is higher than ever before,” said Raina MacIntyre, an epidemiologist at the University of New South Wales and study coauthor. She’s studied influenza for more than thirty years. “We need to really understand how it’s spreading, the role of newly infected species, and what that means in terms of risks. That gives us a better chance to mitigate those risks.”

“Using geospatial analysis techniques is key to understanding global changes in avian influenza” said Samsung Lim, a geographic information system expert at the University of New South Wales and study coauthor. “We combined GIS with epidemiology to better characterize how and why H5N1 has escalated in such an unprecedented way.”

The study was published in GeoHealth, which investigates the intersection of human and planetary health for a sustainable future.

Bird flu then and now

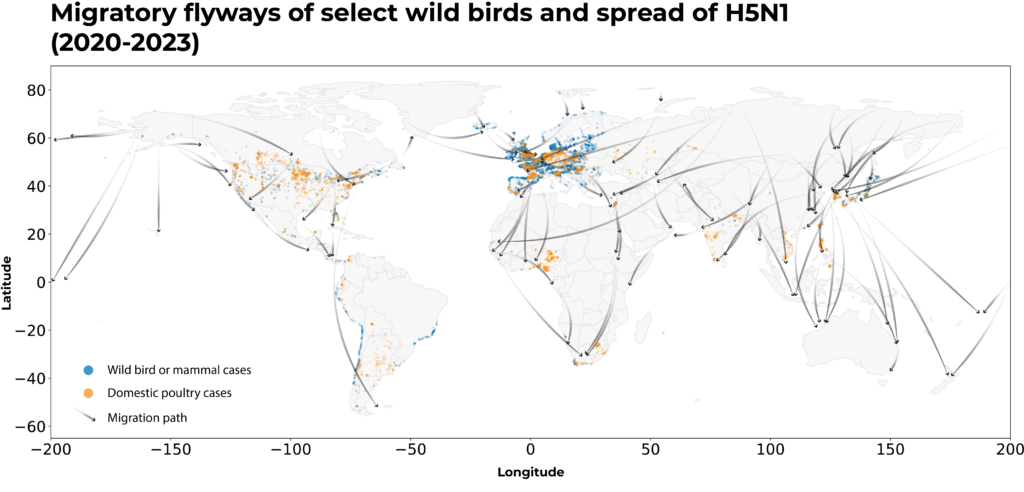

MacIntyre and her colleagues wanted to see when and where outbreaks happened, what species were affected, and where those species flew. The researchers used machine learning to track H5N1 outbreaks and trace the virus’ spread from 1997 to 2023.

They combined data from wild birds and poultry operations to assess when and where the two groups mixed, presenting the first comprehensive analysis of avian flu’s spread in recent decades, highlighting new species and flyways that are vectors of spread.

Birds migrate long distances using avian superhighways called flyways, which criss-cross the globe, punctuated with convenient stopover points for weary birds. There, bird species mix and mingle, including with poultry birds. It’s a perfect petri dish for the H5N1 virus to evolve in.

Ducks, geese and swans have historically been the main wild birds responsible for carrying H5N1, but they were painted as victims of infected poultry rather than a responsible party. But H5N1’s global spread and shifting hotspots have brought that assumption under question.

The first significant outbreak of H5N1 was in Hong Kong in 1997, when 18 humans were infected following contact with chickens. Of those infected, six died. Another outbreak hit in 2005, when there were mass die-offs of wild birds at China’s largest lake. The disease began spreading to Europe, and from there on to Africa and the Americas. By 2010, H5N1 had infiltrated 55 countries, hinting at the role wild birds play in carrying the virus. Outbreaks then occurred in 2014-2015 and, most recently, 2020 to today.

“Until 2020, the pattern of H5N1 was very sporadic,” MacIntyre said. “We’d see an outbreak and then it would die down.” The outbreak that began in 2020 has failed to die down, despite the use of culling that has historically helped end avian flu outbreaks.

H5N1 has primarily been carried by migratory ducks, geese and swans. But new species, such as peregrine falcons and pelicans, are now spreading the disease, taking it to new flyways. Credit: AGU, modified from Jindal et al. (2025)

Wild birds: Victims and vectors

Far more bird species than ducks, geese and swans are transporting highly pathogenic H5N1 today, the study found. Cormorants, pelicans, buzzards, vultures, hawks, and peregrine falcons play significant roles in spreading avian flu. That makes them both victims and vectors of the disease and upends traditional approaches to monitoring H5N1 spread and predicting and responding to outbreaks. Culling of poultry birds worked in the past to mitigate burgeoning outbreaks, but it has failed to stop the current outbreak.

“We’ve got to think beyond ducks, geese and swans,” MacIntyre said. “They’re still important, but we have to start looking closely at these other species and other routes and think about what new risks that brings.”

Monitoring wild birds at a global scale is very difficult, so managing poultry bird populations is all the more important, she said. “We can do more about factors in our control — agriculture and farming.” Free-range birds, for instance, are more likely to contact wild birds, so managing them requires more vigilance. And pigs are “an ideal genetic mixing vessel” for viruses, so keeping pigs and poultry in close proximity is dangerous, she said.

“It’s a global problem, and it requires global solutions,” MacIntyre said.

Notes for journalists:

This study is published in GeoHealth, an open-access AGU journal. View and download a pdf of the study here. Neither this press release nor the study is under embargo.

Paper title:

“A geospatial perspective towards the role of wild bird migrations and global poultry trade in the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1”

Authors:

- Samsung Lim (corresponding author), Mehak Jindal, School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Biosecurity Program at the Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales Sydney, New South Wales, AUS

- Haley Stone, Biosecurity Program at the Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales Sydney, New South Wales, AUS

- Raina MacIntyre, Biosecurity Program at the Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; and College of Health Solutions and College of Public Service & Community Solutions, Arizona State University, AZ, USA

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.