5 September 2018

WASHINGTON — Bottlenose dolphins are being exposed to chemical compounds added to many common cleaning products, cosmetics, personal care products and plastics, according to a new study in GeoHealth, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

The new research found evidence of exposure to these chemical compounds, called phthalates, in 71 percent of dolphins tested in Sarasota Bay, Florida during 2016 and 2017. Previous studies detected phthalate metabolites in the blubber or skin of a few individual marine mammals, but the new study is the first to document the additives in the urine of wild marine mammals.

A bottlenose dolphin swims in Sarasota Bay.

Credit: Photo taken by Sarasota Dolphin Research Program under National Marine Fisheries Service Scientific Research Permit No. 20455.

Some phthalates have been linked to hormonal, metabolic and reproductive problems in humans, including low sperm count and abnormal development of reproductive organs. The study’s authors do not know what health impacts phthalate compounds may have on dolphins, but the presence of byproducts of the chemicals in the animals’ urine indicates they have remained in the body long enough to process them.

“We focused on urine in dolphins because, in previous studies of humans, that has been the most reliable matrix to indicate short-term exposure.” said Leslie Hart, a public health professor at the College of Charleston and the lead author of the new study.

Studies have linked human exposure to phthalates with use of products containing these additives, such as personal care products and cosmetics, but Hart said the source of dolphin exposure to phthalates is not yet known. Elevated concentrations in dolphin urine of a specific phthalate compound most commonly added to plastics hinted at plastic waste as a possible source of exposure for the dolphins, she said.

“These chemicals can enter marine waters from urban runoff and agricultural or industrial emissions, but we also know that there is a lot of plastic pollution in the environment” said Hart.

Understanding exposure in dolphins gives scientists insight into the contaminants in local waters and what other animals, including humans, are being exposed to, according to the study’s authors.

Gina Ylitalo, an analytical chemist at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center who was not involved in the study, said dolphins are good indicators of what is going on in coastal waters.

“Any animals in the near shore environment with similar prey are probably being exposed as well,” she said. “The dolphins are great sentinels of the marine environment.”

Ubiquitous contaminants

Phthalate compounds are added to a wide variety of products to confer flexibility, durability, and lubrication. Some phthalates interfere with body systems designed to receive messages from hormones such as estrogen and testosterone. This can disrupt natural responses to these hormone signals.

Tests for phthalate exposure look for metabolites of the compounds, the products of initial breakdown of the compounds by the liver.

“We are looking for metabolites. These are indicators that the dolphins have been exposed somewhere in their environment and that the body has started to process them,” Hart said.

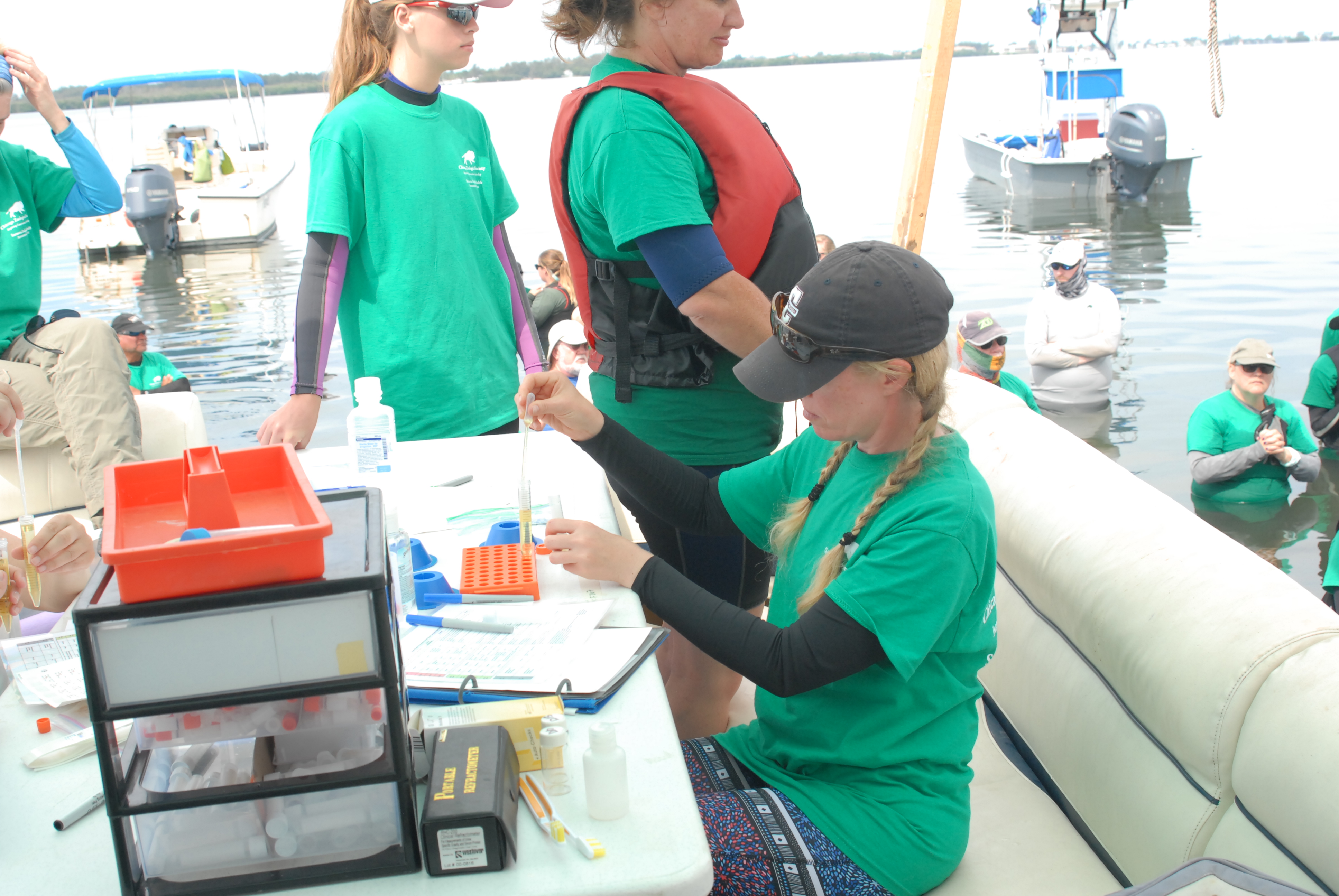

Researcher Leslie Hart processes dolphin urine to test for exposure of the animals to phthalates, chemical compounds added to a wide variety of common cleaning products, cosmetics, personal care products and plastics.

Credit: Chicago Zoological Society’s Sarasota Dolphin Research Program

About 160 dolphins live in Sarasota Bay, a subtropical coastal lagoon tucked between barrier islands and the cities of Sarasota and Bradenton on the southwest coast of Florida. The Chicago Zoological Society’s Sarasota Dolphin Research Program has tracked individual dolphins since 1970, monitoring their health, behavior, and exposure to contaminants. The dolphins are residents of the area year-round, across multiple decades, with individuals living up to 67 years.

In 2016 and 2017, Hart and her colleagues tested the urine of 17 wild dolphins in and around Sarasota Bay for nine phthalates. They found phthalate metabolites in the urine of 71 percent of the dolphins tested.

Hart compared the dolphin data to human data from the CDC’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which includes information about behavior and diet as well as blood and urine samples from a large cross section of the U.S. population. She found concentrations of one type of phthalate metabolite, monoethyl phthalate (MEP), were much lower in dolphins than in the human population surveyed by NHANES, but concentrations of another type of phthalate metabolite, mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), were equivalent or higher to the levels found in humans.

“If you look at the primary uses of the parent compounds, MEP’s parent is commonly used in cosmetics and personal care products including shampoos and body wash, whereas MEHP is a metabolite of a compound commonly added to plastic,” Hart said.

Indicator species

Understanding what dolphins are exposed to gives researchers and the public a better idea of what is in the environment.

The study is particularly valuable because of the long-term data available on the Sarasota dolphins’ health and behavior, said Ylitalo. Bottlenose dolphins are good indicators of pollutant exposure in whales and dolphins that can’t be easily sampled.

“We will not be getting urine samples from killer whales in my neck of the woods,” Ylitalo said. “They don’t know what the health effects are yet, but if any group can do it, it will be these type of folks who start teasing it out.”

Documenting exposure was an important first step, Hart said. She wants to expand the sample size to continue investigating the extent and potential health impacts of exposure and start tracking down possible sources. Ultimately, she hopes this research could be used to help curtail the sources of contamination.

“We’ve introduced these chemicals, they are not natural toxins, and we have the ability to reverse it, to clean this up.” Hart said.

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing 60,000 members in 137 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

Notes for Journalists

This paper is open access. Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) can download a PDF copy of the article by clicking on this link:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2018GH000146

Multimedia accompanying this press release can be downloaded here:

https://aguorg.sharepoint.com/:f:/s/newsroom/EnNXZmVdpNFNkkM1h9V33DMB4uLef1zjvIpRkQUWk299vQ

Journalists and PIOs may also request a copy of the final paper and multimedia by emailing Liza Lester at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Urinary phthalate metabolites in common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from Sarasota Bay”

Authors:

Leslie B. Hart and Moriah Alten Flagg: Department of Health and Human Performance, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC.

Barbara Beckingham: Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC.

Randall S. Wells: Chicago Zoological Society’s Sarasota Dolphin Research Program, Mote Marine Laboratory, Sarasota, FL.

Kerry Wischusen: Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC.

Amanda Moors and John Kucklick: National Institute of Standards and Technology, Charleston, SC.

Emily Pisarski: JHT Inc., Hollings Marine Laboratory, Charleston, SC.

Ed Wirth: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/National Ocean Service/National Center for Coastal Ocean Science, Charleston, SC.

Contact information for the authors:

Leslie Hart: [email protected], +1 (843) 953-5191

Liza Lester

+1 (202) 777-7494

[email protected]