Climate change likely to make global precipitation more uneven

15 November 2018

WASHINGTON — Currently, half of the world’s measured precipitation that falls in a year falls in just 12 days, according to a new analysis of data collected at weather stations across the globe.

In a new study in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, climate models project this lopsided distribution of rain and snow is likely to become even more skewed by century’s end, with half of annual precipitation falling in 11 days.

Shown here is TRMM’s long term rainfall data merged with other satellites’ rain data from 40N to 40S latitude. The colors show the average of all the monthly rain averages from 1998 to 2010. Credit: Precipitation Processing System/NASA Goddard

Previous studies have shown that we can expect both an increase in extreme weather events and a smaller increase in average annual precipitation in the future as the climate warms, but researchers are still exploring the relationship between those two trends.

“This study shows how those two pieces fit together,” said Angeline Pendergrass, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado and the lead author of the new study. “What we found is that the expected increases happen when it’s already the wettest — the rainiest days get rainier.”

The findings, which suggest flooding and the damage associated with it could also increase, have implications for water managers, urban planners, and emergency responders. The research results are also a concern for agriculture, which is more productive when rainfall is spread more evenly over the growing season.

The research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation, which is NCAR’s sponsor.

What it means to be extreme

Scientists who study extreme precipitation — and how such events may change in the future — have used a variety of metrics to define what qualifies as “extreme.” Pendergrass noticed in some cases the definitions were so broad that extreme precipitation events actually included the bulk of all precipitation.

In those instances, “extreme precipitation” and “average precipitation” became essentially the same thing, making it difficult for scientists to understand from existing studies how the two would change independently as the climate warms.

Other research teams have also been grappling with this problem. For example, a recent paper tried to quantify the unevenness of precipitation by adapting the Gini coefficient, a statistical tool often used to quantify income inequality, to instead look at the distribution of rainfall.

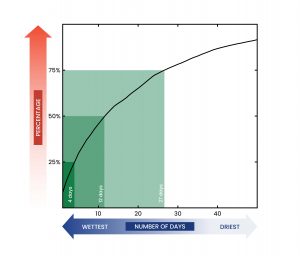

Pendergrass wanted to find something even simpler and more intuitive that could be easily understood by both the public and other scientists. In the end, she chose to quantify the number of days it would take for half of a year’s precipitation to fall. The results surprised her.

“I would have guessed the number would be larger — perhaps a month,” she said. “But when we looked at the median, or midpoint, from all the available observation stations, the number was just 12 days.”

Analysis of rainfall across the globe between 1999 and 2014 found that the median time it took for half of a year’s precipitation to fall was just 12 days. A quarter of annual precipitation fell in just six days, and three-quarters fell in 27 days. Credit: UCAR/Simmi Sinha

For the analysis, Pendergrass worked with Reto Knutti, of the Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science in Zurich, Switzerland. They used data from 185 ground stations for the 16 years from 1999 through 2014, a period when measurements could be validated against data from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite. While the stations were dispersed globally, the majority were in North America, Eurasia, and Australia.

To look forward, the scientists used simulations from 36 of the world’s leading climate models that had data for daily precipitation. Then they pinpointed what the climate model projections for the last 16 years of this century would translate to for the individual observation stations.

They found total annual precipitation at the observation stations increased slightly in the model runs, but the additional precipitation did not fall evenly. Instead, half of the extra rain and snow fell over just six days.

This contributed to total precipitation also falling more unevenly than it does today, with half of a year’s total precipitation falling in just 11 days by 2100, compared to 12 in the current climate.

“While climate models generally project just a small increase in rain in general, we find this increase comes as a handful of events with much more rain and, therefore, could result in more negative impacts, including flooding,” Pendergrass said. “We need to take this into account when we think about how to prepare for the future.”

The University Corporation for Atmospheric Research manages the National Center for Atmospheric Research under sponsorship by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing 60,000 members in 137 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

The University Corporation for Atmospheric Research manages the National Center for Atmospheric Research under sponsorship by the National Science Foundation. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. On the web: http://www2.ucar.edu/atmosnews On Twitter: @NCAR_Science

Notes for Journalists

This paper is freely available for 30 days. Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) can download a PDF copy of the article by clicking on this link:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2018GL080298

Journalists and PIOs may also request a copy of the final paper and multimedia by emailing Lauren Lipuma at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“The Uneven Nature of Daily Precipitation and Its Change”

Authors:

Angeline Pendergrass: National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), Boulder, Colorado, U.S.A;

Reto Knutti: Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science, ETH‐Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Contact information for the authors:

Angeline Pendergrass

303-497-1743

[email protected]

Lauren Lipuma

+1 (202) 777-7396

[email protected]

NCAR/UCAR Press Contacts:

David Hosansky, NCAR/UCAR Manager of Media Relations

303-497-8611

[email protected]

Laura Snider, NCAR/UCAR Senior Science Writer and PIO

303-497-8605

[email protected]