Landscape changes during the urbanization of a New York City bay, in combination with sea level rise, have made high-tide flooding a chronic issue for coastal residents.

23 February 2023

The chronic high-tide flooding residents of Jamaica Bay, N.Y. experience is accentuated by historic dredging and wetland loss, according to a new study in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. | Credit: Jeffrey Bary via flickr

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, [email protected] (UTC-5 hours)

Contact information for the researchers:

Philip Orton, Stevens Institute of Technology, [email protected] (UTC-5 hours)

WASHINGTON — Historical dredging and wetland loss in New York City’s Jamaica Bay have increased high-tide flooding in the area, according to a new study.

Jamaica Bay is an estuary that lies between Long Island and New York City’s Brooklyn and Queens boroughs. Over the past 150 years, landscape changes and sea level rise have increased high-tide levels in the bay by 55 centimeters (1.8 feet). As a result, hundreds of thousands of residents experience chronic, damaging floods.

“Some neighborhoods around Jamaica Bay flood about 60 times per year,” said Philip Orton, a physical oceanographer at the Stevens Institute of Technology and corresponding author of the study. “This forces the community to make infrastructure changes, like putting backflow valves in sewers to prevent water from coming up during flooding events.”

The study was published in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, which features science that advances our understanding of the ocean and its processes.

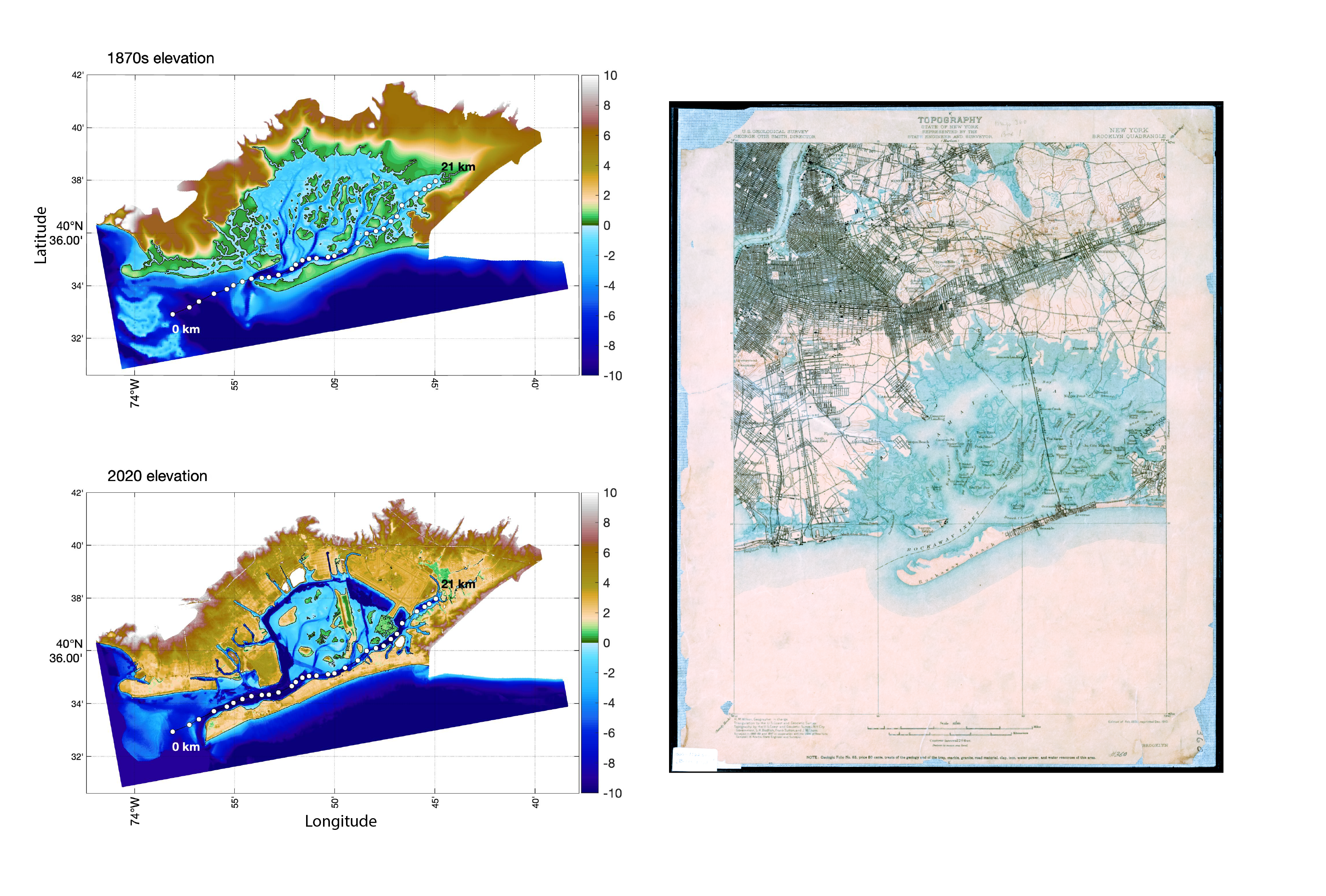

Researchers used water level observations and digitized landscape maps that extend back to the 1870s to model the effects of sea level rise and land-use changes, including the extension of Rockaway Peninsula and the dredging and widening of the inlet, on high-tide flooding in the bay. They then compared modern flood risks to hypothetical scenarios in which humans did not alter the landscape.

A map of the elevation and bathymetry of Jamaica Bay estuary in New York City in the 1870s and in 2020 is side-by-side an 1888-1889 survey map of Jamaica Bay showing the morphology and marsh cover (in blue), taken from Powell (1891) | Credit: left: Pareja-Roman et al. (2023), right: USGS.

In 2020, 15 of the 62 high-tide events that impacted Jamaica Bay were classified by NOAA as “minor” floods, resulting in flood advisories throughout the bay. According to the study, only 2 of the 15 minor flooding events that impacted Jamaica Bay in 2020 would have occurred if there hadn’t been historical landscape changes in the bay, and only 1 of the 15 would have occurred without sea level rise.

“We know that flooding is going to get worse, and institutions will have to plan to provide aid to people living in the area,” said Alfredo Aretxabaleta, an oceanographer at the United States Geological Survey with no affiliation to the study. “This research provides the framework to identify the most beneficial ways in which to lessen the impact of minor flooding in shallow, urbanized coastal lagoons.”

“Minor” flooding, major problems

Minor flooding events, often called nuisance flooding, are floods that result in minimal property damage but may pose a public threat or inconvenience. “Basically, when there is street flooding, it is considered a minor flooding event,” Orton said.

Minor high-tide flooding events frequently cause streets in the neighborhoods surrounding Jamaica Bay in New York City to flood. | Credit: Philip Orton

High-tide floods often fall under the category of “minor” floods, but chronic minor floods — such as the those that residents face monthly around Jamaica Bay — can disrupt the livelihoods of the bay’s residents and cause infrastructure damage over the years.

“We thought that the main [flooding] problem was going to be that the inlet was deepened dramatically since the 1870s,” Orton said. “But it turns out that the destruction of the surrounding wetlands was also an important factor in the flooding dynamics of the estuary.”

The wetlands surrounding the bay had absorbed the tidewaters, reducing flooding by allowing the water to spread over a wider area. Since the late 1800s, 46.5 square kilometers (18 square miles), or 76%, of the total wetland area was lost due to erosion, inlet deepening and the creation of new urban spaces. Today, neighborhoods are built on top of the remaining wetlands.

“When people think of flooding, they tend to consider it as a result of extreme events, like hurricanes,” said Aretxabaleta. “Minor floods may not be as detrimental as hurricanes, but they can flood your basement and damage the foundation of your house, and people are getting tired of dealing with them.”

It doesn’t help that many communities vulnerable to chronic high-tide flooding in the United States are located where tropical storms and hurricanes tend to hit, Aretxabaleta added.

“At many locations across the nation, high tides are getting higher thanks to sea level rise,” Orton said. “Many of the developed coastal lagoons throughout the country, and even throughout the world, are being hit with a growing number of high-tide flooding events.”

Restoring wetlands and marshes around the edges of Jamaica Bay could help reduce high-tide flooding, Orton said.

###

Contributed by Kirsten Steinke

###

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists:

This study is open access. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo. Download a PDF copy of the paper here.

Related studies published recently in AGU’s journal Earth’s Future found that more than half of U.S. coastal communities underestimate the risks of sea level rise and that the worse impacts of sea level rise will hit earlier than expected.

This study is a follow-up to a recent study in Science Advances by the authors, which demonstrated tides are growing larger in many U.S. estuaries.

Paper title:

“Effect of estuary urbanization on tidal dynamics and high tide flooding in a coastal lagoon”

Authors:

- L. Fernando Pareja-Roman (corresponding author), Department of Civil, Environmental, and Ocean Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ, USA and Now at Department of Marine and Coastal Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA

- P. Orton (corresponding author), Department of Civil, Environmental, and Ocean Engineering, Stevens Institute of Technology, Hoboken, NJ, USA

- S. Talke, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, California Polytechnic University-San Luis Obispo, San Luis Obispo, CA, USA