21 October 2014

WASHINGTON D.C. — Humans have long dreamed of traveling to Mars, hopscotching across the solar system and fanning out into the cosmos beyond. Several nations and private organizations are developing plans for crewed Mars missions in the coming decades. But a new study shows that increasing levels of cosmic radiation spurred by weak solar activity could make such journeys more risky to the health of their crews, raising questions about the feasibility of those missions.

The new research finds that, during periods of low solar activity, a 30-year-old astronaut can spend roughly one year in space—just enough time to get to Mars and back—before the constant bombardment by cosmic rays pushes the risk of radiation-induced cancer above current exposure limits.

When the sun is active, its magnetic field intensifies. The magnetic field deflects galactic cosmic rays away from the solar system. If the sun’s activity continues to weaken, the number of days humans could safely spend in deep space could decrease by about 20 percent.

Credit: NASA

If the sun’s activity continues to weaken as many scientists predict, the number of days humans could spend in deep space before reaching their exposure limit could decrease by about 20 percent, making future crewed space flight more dangerous, according to the new study accepted for publication in Space Weather, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

To estimate solar activity, scientists count sunspots— dark spots on the surface of the sun caused by bursts of magnetic activity. When the sun is active, the frequency of sunspots and eruptions of energetic matter from its surface increase, and the sun’s magnetic field intensifies. The magnetic field deflects cosmic radiation away from the solar system, but a recent trend of declining solar activity means the sun’s magnetic field is weak. The weakened magnetic field allows more cosmic rays to overrun the solar system, increasing the radiation hazard to astronauts, according to the study’s authors. Solar activity reached its lowest level in the space age in 2009 during the last solar minimum, and scientists think the next minimum may shatter even those records as the sun grows more deeply subdued.

“While these conditions are not necessarily a showstopper for long-duration missions to the moon, an asteroid, or even Mars, galactic cosmic ray radiation in particular remains a significant and worsening factor that limits mission durations,” said Nathan Schwadron, associate professor at the Institute for the Study of Earth, Oceans, and Space and the Department of Physics at the University of New Hampshire in Durham, and lead author of the new paper.

“Cosmic rays are the most energetic particles in the universe,” said Richard Mewaldt, a physicist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, who was not involved in the study. Supernova explosions in the far-off corners of the galaxy send galactic cosmic rays rocketing towards the solar system at nearly the speed of light. Their high energy allows these particles to penetrate nearly every material known to man, including shielding on space craft. When the cosmic rays penetrate that shielding, secondary particles are produced that can damage organs and lead to cancer, said Schwadron.

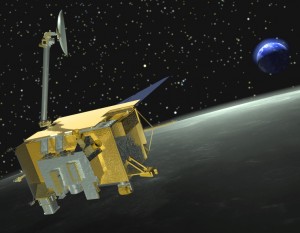

NASA sets limits on how much cosmic radiation exposure is safe for astronauts. Using measurements from the Cosmic Ray Telescope for the Effects of Radiation (CRaTER) aboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, the study’s authors were able to estimate the amount of time it would take an astronaut to reach the agency’s maximum allowed radiation exposure. CRaTER uses a material called “tissue equivalent plastic” that mimics human muscle to gauge radiation dosage over time.

Artist’s rendition of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter at the moon. The CRaTER telescope is seen pointing out at the bottom right center of the LRO spacecraft.

Credit: Chris Meaney/NASA

The researchers found it would take just under 400 days for a 30-year-old male astronaut to reach the maximum radiation dose, and just under 300 days for a 30-year-old female astronaut to reach the same dosage during the last solar minimum. If solar activity continues to decrease, causing cosmic radiation levels to increase, those numbers could drop to less than 320 days for a 30-year-old man and less than 240 days for a 30-year-old woman in four to six years, according to the new study. These numbers will vary with both the age of the astronauts and the sun’s activity level, the study notes.

Schwadron and his colleagues were motivated to examine the implications of weak solar behavior on human space exploration after solar physicists started raising the possibility that the current solar cycle – the weakest 11-year cycle in more than 80 years – could be part of a long-term trend of declining solar activity.

During the 2009 solar minimum, the sunspot number went down to its lowest level in 100 years, and the magnetic field was the weakest that it had been in the space era, according to Mewaldt.

Now the sun is entering what many are calling the “mini-maximum”, anticipated to be the smallest solar maximum that modern scientists have ever directly observed, according to Schwadron.

“Over time, it’s become increasingly clear that the space environment is not returning to normal,” Schwadron said. “There’s been a sustained change in the way the sun is behaving.”

Extended periods of below-normal solar activity have occurred in the past, most notably during the 80-year Maunder minimum, which began in the mid-1600s and was marked by a near total absence of sunspots.

Schwadron cautioned that the projections outlined in the new study are tentative, and they are not definitive forecasts of how long future space flights should last. But they do demonstrate how the changing solar environment could impact space travel.

“[This research] is helping us,” Schwadron said, “to prepare for and plan for human exploration in the future.”

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 62,000 members in 144 countries. Join our conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and other social media channels.

Notes for Journalists

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of this article by clicking on this link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2014SW001084/abstract

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Kate Wheeling at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Does the worsening galactic cosmic radiation environment observed by CRaTER preclude future manned deep-space exploration?”

Authors:

Nathan Schwadron: University of New Hampshire, Space Science Center, Durham, NH, USA;

J. B. Blake: The Aerospace Corporation, El Segundo, CA, USA;

A. W. Case: High Energy Astrophysics division, Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA, USA;

C. Joyce: University of New Hampshire, Space Science Center, Durham, NH, USA;

J. Kasper: High Energy Astrophysics division, Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Cambridge, MA, USA; Department of Atmospheric, Oceanic and Space Sciences, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA;

J. Mazur: The Aerospace Corporation, El Segundo, CA, USA;

N. Petro: Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA;

M. Quinn: University of New Hampshire, Space Science Center, Durham, NH, USA;

J. A. Porter: Dept of Nuclear Engineering, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA;

C. Smith, S. Smith, and H. E. Spence: University of New Hampshire, Space Science Center, Durham, NH, USA;

L. W. Townsend: Dept of Nuclear Engineering, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA;

R. Turner: Analytic Services Inc, Arlington, VA, USA;

C. Zeitlin: Southwest Research Institute, Earth Oceans and Space Science, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA.

Contact information for the authors:

Nathan Schwadron: +1 (603) 862-3451; [email protected]

Kate Wheeling

+1 (202) 777-7516

[email protected]

University of New Hampshire Contact:

David Sims

+1 (603) 862-5369

[email protected]