A ton of lead dust may have been deposited near the cathedral

9 July 2020

Notre Dame cathedral burns on 15 April 2019.

Credit: GodefroyParis, Wikimedia Commons

AGU contact: Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, [email protected]

Lamont-Doherty contact: Sarah Fecht, [email protected], +1 212-854-8050

Contact information for the researchers:

Alexander van Geen, [email protected], +1 646-379-7843

WASHINGTON—On April 15, 2019, the world watched helplessly as black and yellow smoke billowed from the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. The fire started just below the cathedral’s roof and spire, which were covered in 460 tons of lead — a neurotoxic metal, dangerous especially to children, and the source of the yellow smoke that rose from the fire for hours. The cathedral is being restored, but questions have remained about how much lead the fire emitted into the surrounding neighborhoods, and how much of a threat it posed to the health of people living nearby.

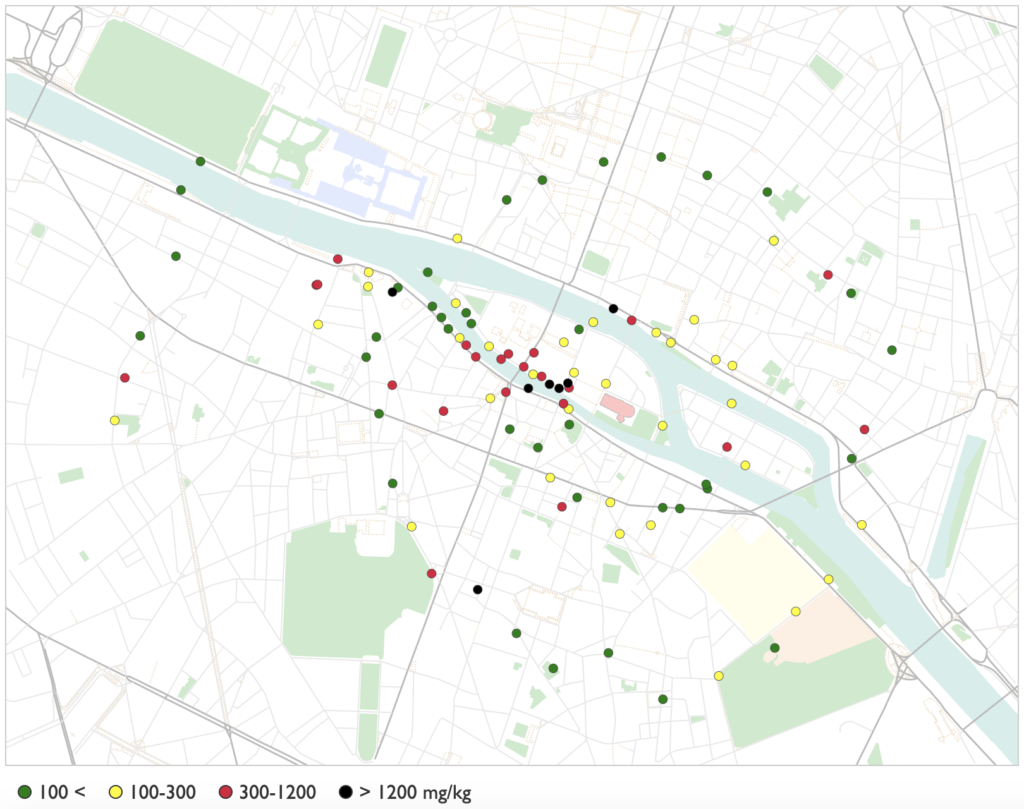

A new study, published today in AGU’s journal GeoHealth, used soil samples collected from neighborhoods around the cathedral to estimate local amounts of lead fallout from the fire. Lead levels in the soil samples indicated that nearly a ton of lead dust dropped down within one kilometer (0.6 miles) of the site, and areas downwind of the fire had double the lead levels than sites that were outside the path of the smoke plume. The study concludes that, for a brief time, people residing within a kilometer and downwind of the fire were probably more exposed to lead fallout than measurements by French authorities indicated.

Early evidence suggested that the fire increased lead exposure in Paris. Air quality measurements taken 50 kilometers away from the cathedral found that lead particulates in the air were 20 times higher than usual in the week after the fire. However, a small set of measurements by France’s Regional Health Agency, posted weeks after the fire, found that all the samples collected outside of the out-of-bounds area around the cathedral had lead levels below France’s limit of 300 milligrams per kilogram of soil. At the time, there were fears that the health agency was underplaying the potential health impacts and not being transparent enough.

“There was a controversy — were children being exposed or not from this fallout?” said Lex van Geen, a geochemist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and lead author on the new study. “So I thought, whether I get a ‘yes’ or a ‘no,’ it’s worth documenting.”

In December 2019 and February 2020, van Geen collected 100 soil samples from tree pits, parks and other locations around the cathedral, and in particular to the northwest, where most of the smoke traveled on the day of the fire. When lead enters soil, it tends to stay put, so it can preserve the signal of the fallout for much longer than hard surfaces such as roads and sidewalks, which get swept and flushed by rain.

“It wasn’t a particularly glamorous expedition,” said van Geen. “I got plenty of strange looks from people wondering why this old guy was scooping up soil, trying to avoid the dog poop, and putting some of the soil in paper bags. But it got done.”

Non-contaminated soil would be expected to contain less than less than 100 milligrams of lead per kilogram of soil. However, in samples collected within a kilometer the cathedral’s remains, the levels averaged 200 mg/kg. And in the northwest direction downwind of the fire, the lead was significantly higher, averaging nearly 430 mg/kg — double that of the surrounding area, and surpassing France’s 300 mg/kg limit.

Interactive Map: Soil lead levels near Notre Dame cathedral, Paris

Circles indicate where discrete soil samples were collected and are colored according to their lead content in milligrams per kilogram of soil (mg/kg, also referred to as parts per million or ppm). [View interactive map]

Credit: Jeremy Hinsdale

“Our final estimation of the total amount of excess lead is much larger compared with what has been reported earlier by other teams,” said Yao. “Of course, we are measuring slightly different things, but ultimately all disagreement in scientific findings shall be validated by more data, especially when they have profound policy and public health consequences. I hope our work sheds some light in that direction.”

It is difficult to ascertain how this lead may have affected human health, because too few soil, dust, and blood samples were collected immediately after the fire, said van Geen. The impacts are likely much lower than those of leaded gasoline, which was entirely phased out by the year 2000. Nevertheless, lead could have posed a brief but significant health hazard to children living downwind of the fire.

On June 4, seven weeks after the fire, the French government made blood tests available at a local hospital on an on-demand basis. This only occurred after a child in a nearby apartment was found to have a concerning level of lead in their blood. (Subsequent investigation identified a different source of lead as the more likely culprit in this case.) Soil and dust tests were similarly delayed and limited in scope.

To van Geen, the government showed it had the means to respond but it didn’t do so quickly enough. He says that the urgency of the situation should have been more clearly conveyed with pro-active collection and posting of environmental and blood-lead data. This would have induced more parents downwind of the fire to remove indoor dust with wet wipes at home and prevent kids from playing in soil, thereby reducing their chances of exposure.

AGU (www.agu.org) supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists

This paper is open access. Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) can download a PDF copy of the article by clicking on this link: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2020GH000279

Journalists and PIOs may also request a copy of the final paper by emailing Liza Lester at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper Title

“Fallout of lead over Paris from the 2019 Notre‐Dame cathedral fire”

Authors

Alexander van Geen and Tyler Ellis, Lamont‐Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA

Yuling Yao and Andrew Gelman, Department of Statistics, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA