17 February 2021

An ozonesonde launches at Hohenpeissenberg Meteorological Observatory, Germany. The ozone sensor is in the white styrofoam cylinder dangling from the balloon, which will carry the sensor up to 30 or 35 kilometers (115,000 feet) altitude. For handling at launch, the ozone sensor is close to the balloon, but an unwinder increases the distance between balloon and sensor to about 30 meters during flight.

Credit: Ulf Köhler (DWD Hohenpeissenberg).

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, [email protected] (UTC -5:00)

Deutscher Wetterdienst contact:

Gertrud Nöth, +49 69-8062-4505, [email protected] (UTC +1:00)

Contact information for the researchers:

Wolfgang Steinbrecht, DWD Hohenpeissenberg, +49 69-8062-9772, [email protected] (UTC +1:00)

WASHINGTON—During spring and summer of 2020, ozone at 1-8 kilometers (0.6-5 miles) above Earth’s surface fell by 7% on average across the Northern Hemisphere, a new study finds. The decrease is likely explained by curtailed transportation due to COVID-19 quarantines, according to the report, published in Geophysical Research Letters, AGU’s journal for high-impact, short-format reports with immediate implications spanning all Earth and space sciences.

Worldwide, surface traffic emissions went down by 14% and air-traffic emissions by 40% on average in 2020.

The new study analyzed data from weather balloons and remote sensing instruments from 45 stations. Many of the observatories saw similar ozone decreases in this layer of the atmosphere, to levels which had not been recorded in two decades.

“This is a remarkably large ozone reduction, over a very big region,” said Wolfgang Steinbrecht, an atmospheric scientist at Deutscher Wetterdienst’s (the German weather service’s) Hohenpeissenberg Meteorological Observatory, and lead-author of the study. “The last time we’ve seen such low free tropospheric ozone in Hohenpeissenberg was 1976.”

About 90% of Earth’s ozone is produced naturally through sunlight driven reactions in the stratosphere, a layer of the atmosphere about 10-50 kilometers (6-30 miles) above Earth’s surface, separated from the ground level atmosphere by jet streams. This “good” ozone absorbs harmful ultraviolet light and is essential to life on Earth.

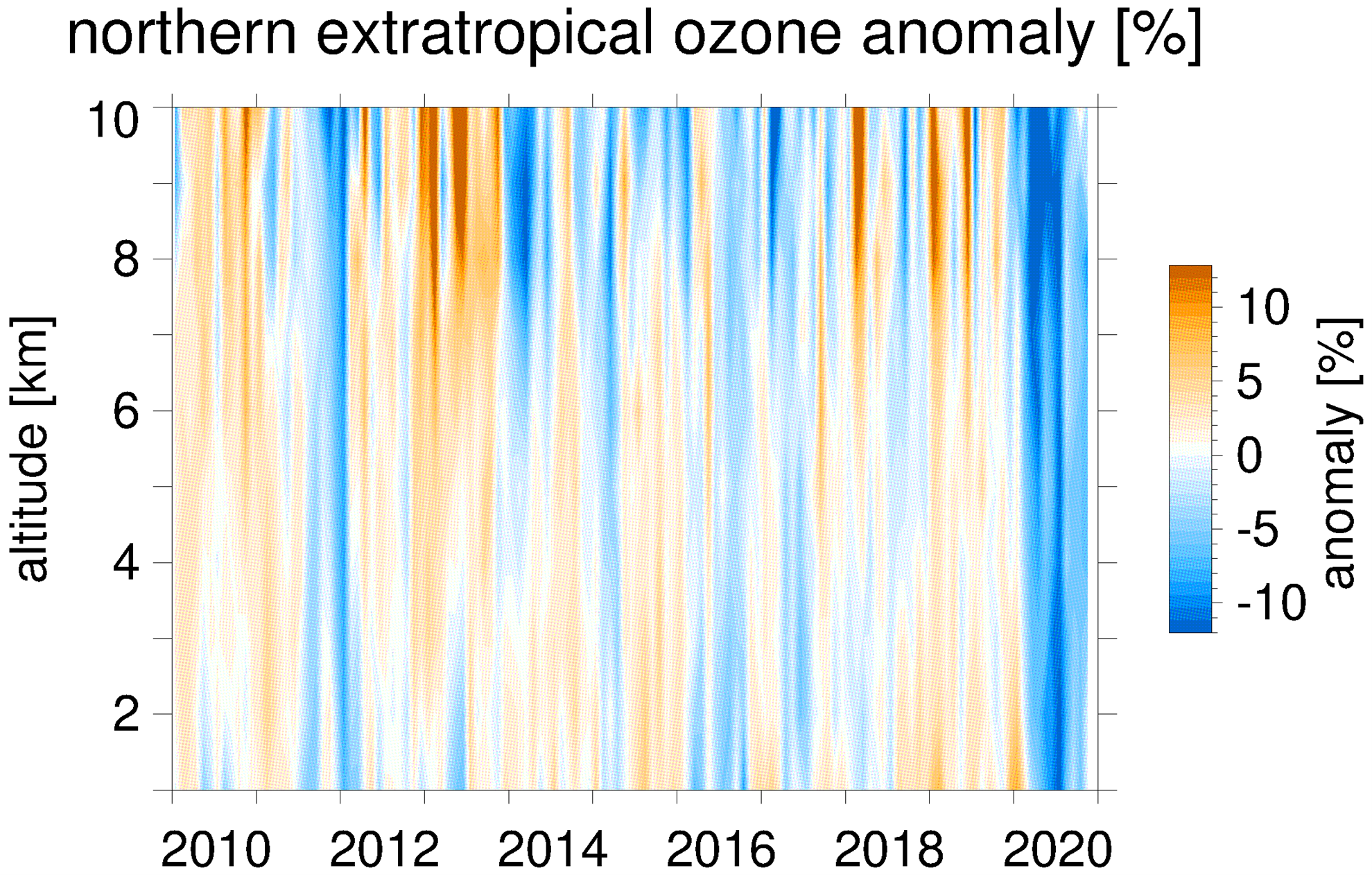

Red colors indicate more ozone than normal, blue colors less ozone than normal, in this color plot of ozone anomalies for the northern extra-tropics for the years 2010 to 2020, and altitudes from 1 to 10 kilometers. The blue band in the year 2020 indicates the unusually low ozone in the free troposphere, due to the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Credit: Geophysical Research Letters/AGU

Ozone in the atmosphere from the ground to about 10 kilometers (6 miles), the layer called the troposphere, is largely a pollutant generated by human industry and transportation, and a component of smog. This “bad” ozone is created by chemical reactions with nitrogen oxides (NOx) produced in fossil fuel combustion and with volatile organic compounds mostly produced by plants. Breathing ozone in high enough concentrations inflames the lungs, worsens existing health conditions like asthma, emphysema and bronchitis and can increase the risk of heart attack and stroke.

The results of the new study contrast with ground level findings from recent studies in congested cities, which reported ozone concentrations increasing by 10 to 30% in some urban locations as nitrogen oxides decreased during quarantines. This can be explained by the complicated chemistry of ozone and other pollutants, Steinbrecht said. In heavily polluted air, nitrogen oxides can destroy ozone, so, counterintuitively, decreasing nitrogen oxides can lead to more ozone.

The new study did not measure ozone at ground level. The measured change in ozone at 1-8 kilometers altitude may be reflected by similar decreases in some cities, but it is unlikely to have notable impacts for people on the ground or stratospheric ozone, Steinbrecht said. The new study did not detect similar changes of stratospheric ozone and the authors do not anticipate the decrease in ozone in the lower atmosphere will impact the ozone hole.

“The implications for human heath are probably a lot smaller than all the other COVID-19 implications I would think,” Steinbrecht said. But the quarantine provides an excellent test case for atmospheric models. Simulations of 2020 conditions by NCAR’s latest Community Atmosphere Model (CAM6.3), which includes atmospheric chemistry, fit the observed ozone data well, according to Steinbrecht.

“Ozone is the poster child for the troposphere because we understand it well,” Steinbrecht said. “The COVID-19 lockdowns are an unplanned global scale atmospheric experiment. They show how complex the atmosphere can react to emission changes. We can learn many things from this, for example, what internationally coordinated emission controls could achieve for air-quality worldwide.”

###

AGU (www.agu.org) supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists

This research study is open access. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

“COVID‐19 Crisis Reduces Free Tropospheric Ozone across the Northern Hemisphere”

Authors:

Wolfgang Steinbrecht, Dagmar Kubistin, Christian Plass-Dülmer, Deutscher Wetterdienst, Hohenpeißenberg, Germany.

Jonathan Davies, David W. Tarasick, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Toronto, Canada.

Peter von der Gathen, Holger Deckelmann, Alfred Wegener Institut, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Polar- und Meeresforschung, Potsdam,Germany.

Nis Jepsen, Danish Meteorological Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Rigel Kivi, Finnish Meteorological Institute, Sodankylä, Finland.

Norrie Lyall, British Meteorological Service, Lerwick, United Kingdom.

Matthias Palm, Justus Notholt, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany.

Bogumil Kois, Institute of Meteorology and Water Management, Legionowo, Poland.

Peter Oelsner, Deutscher Wetterdienst, Lindenberg, Germany.

Marc Allaart, Ankie Piters, Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, DeBilt, The Netherlands.

Michael Gill, Met Éireann (Irish Met. Service), Valentia, Ireland.

Roeland Van Malderen, Andy W. Delcloo, Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium, Uccle, Belgium.

Ralf Sussmann, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, IMK-IFU, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany.

Emmanuel Mahieu, Christian Servais, Institute of Astrophysics and Geophysics, University of Liège, Liège, Belgium.

Gonzague Romanens, Rene Stübi, Federal Office of Meteorology and Climatology, MeteoSwiss, Payerne, Switzerland.

Gerard Ancellet, Sophie Godin-Beekmann, LATMOS, Sorbonne Université-UVSQ-CNRS/INSU, Paris, France.

Shoma Yamanouchi, Kimberly Strong, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Bryan Johnson, NOAA ESRL Global Monitoring Laboratory, Boulder, CO, USA.

Patrick Cullis, Irina Petropavlovskikh, NOAA ESRL Global Monitoring Laboratory, Boulder, CO, USA and Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA.

James W. Hannigan, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO, USA.

Jose-Luis Hernandez, Ana Diaz Rodriguez, State Meteorological Agency (AEMET), Madrid, Spain.

Tatsumi Nakano, Meteorological Research Institute, Tsukuba, Japan.

Fernando Chouza, Thierry Leblanc, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Table Mountain Facility, Wrightwood, CA, USA.

Carlos Torres, Omaira Garcia, Izaña Atmospheric Research Center, AEMET, Tenerife, Spain.

Amelie N. Röhling, Matthias Schneider, Thomas Blumenstock, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, IMK-ASF, Karlsruhe, Germany.

Matt Tully, Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Australia.

Clare Paton-Walsh, Nicholas Jones, Centre for Atmospheric Chemistry, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia.

Richard Querel, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Lauder, New Zealand.

Susan Strahan, Earth Sciences Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA and Universities Space Research Association, Columbia, MD, USA.

Ryan M. Stauffer, Earth Sciences Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA and Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA

Anne M. Thompson, Earth Sciences Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, USA.

Antje Inness, Richard Engelen, European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, Reading, United Kingdom.

Kai-Lan Chang, Owen R. Cooper, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA, and NOAA Chemical Sciences Laboratory, Boulder, CO, USA.

German language release available from Deutscher Wetterdienst