Model-based studies confirm global warming is largely responsible

25 February 2020

WASHINGTON— Over the past 40 years, the major wind-driven current systems in the ocean have steadily shifted toward the poles, according to new research published in AGU’s journal Geophysical Research Letters.

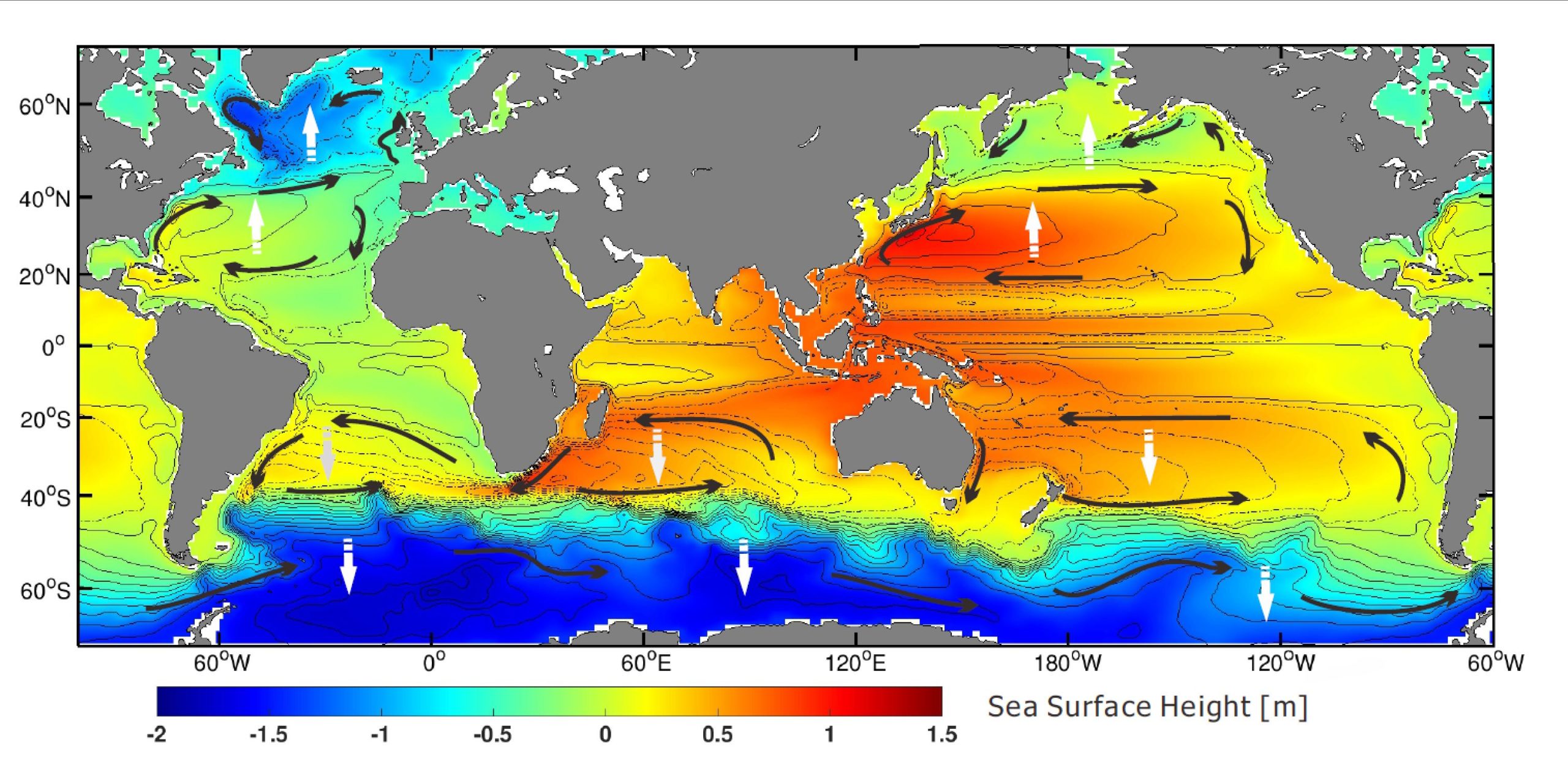

Eight massive wind-driven ocean currents, called ocean gyres, move water around our planet. There are three in the Atlantic Ocean, three in the Pacific Ocean, and one each in the Indian and Antarctic oceans. These rotating current systems largely determine the weather and marine productivity in our planet’s coastal regions.

In the new study, experts at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), analyzed long-term global satellite data of ocean surface temperature and sea levels. Both datasets offer insights into the evolution of large-scale surface currents, and indicate that, in the Northern and Southern Hemisphere alike, the borders of the ocean gyres and their boundary currents are moving closer to the poles, at a rate of more than 800 meters (2,600 feet) per year.

This displacement of tremendous water masses is chiefly driven by global warming, as calculations using a new climate model confirm.

According to the researchers, the consequences of this change can already be felt by human beings and the environment alike. In affected regions, sea levels are rising, indigenous species are migrating, and storms are now following new courses.

Schematic diagram of the major wind-driven ocean circulation (black arrows) and their movement (white arrows) under global warming.

Credit: Hu Yang, Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research

Studying ocean gyres

Until recently, monitoring the ocean gyres globally and on an extended basis was infeasible, due to the enormous costs involved in long-term oceanographic observation. But the AWI experts have developed a new approach. They analyzed long-term satellite data of ocean surface temperature and sea level height, and used the differences in temperature and height to reconstruct the positions and spatial extents of the major current systems.

“When we compared the data, it became clear that, over the past 40 years, all eight wind-driven surface current systems had shifted poleward,” said AWI oceanographer Hu Yang, first author of the new study.

The new method also makes it possible to measure the rate at which these currents are shifting: currently 800 meters (2,600 feet) per year on average.

“These changes are particularly apparent in the Southern Hemisphere. In the Northern Hemisphere, factors like the positions of the continents and changes in the Arctic sea ice also affect the courses of the currents; as a result, we also found considerable natural fluctuations, which motivated us to find out which processes are responsible for the shift, and to what extent,” Yang said.

The influence of global warming

To study the influence of climate change on the ocean gyres, the researchers simulated the evolution of the current systems with a new AWI climate model. In the first simulations, the starting conditions were equivalent to those for a world with the same level of atmospheric carbon dioxide content as in 1850, the dawn of industrialization. The researchers then gradually raised the amount of carbon dioxide in the Earth’s atmosphere until it was twice the 1850 level and calculated the potential current development for a range of initial climatic conditions.

The advanced modeling allowed the team to discriminate between changes caused by global warming, and those produced by natural variations.

“Our calculations for a world with high carbon dioxide values produced the same trends that we saw in the satellite data. And we’re seeing similar changes in the analyses we run with other available model runs from around the globe. In this way, we can show that global warming is a major motor for these shifting currents,” said co-author and AWI climate modeller Gerrit Lohmann.

In addition, the climate simulations offer clues as to which processes in the interaction of the ocean and atmosphere are contributing to the shift.

“We can see, in various types of observational data, and in our model runs, that the winds powering the currents are now moving poleward,” Lohmann said. “How the individual components of the climate system are interlinked in this regard is an aspect we’re now investigating in follow-up projects.”

The team’s new findings build on those from previous studies, which indicated the gyres’ eastern and western boundary currents were moving toward the poles.

“For example, the climate data confirm that during the last ice age, the Agulhas Current was seven degrees of latitude closer to the Equator than it is today,” Yang said.

In order to more precisely measure the speed and the drivers of the shift, the long-term satellite data would need to be combined with historical climate data of the water temperature near the gyres’ borders.

A fundamental change?

These shifts in the major current systems will have far-reaching consequences for human beings and the environment alike, according to the study’s authors.

“As the western boundary currents continue to shift, the courses of winter storms and of the jet stream are following suit,” Yang said. “At the edges of the eastern boundary currents, we’re now seeing the rich ecosystems begin to shrink, because the shifting currents are changing the living conditions too quickly for marine organisms to adapt.”

Dramatic temperature changes have been observed in the Gulf of Maine, due to the shifting Gulf Stream, resulting in a migration of cod stocks. Researchers have observed similar changes off the Atlantic coasts of Uruguay and Argentina, where the Brazil Current is gradually moving south.

In addition, when boundary currents penetrate higher latitudes, the local sea level rises disproportionately – a problem that communities on the northeast coast of North America are now confronted with. To make matters worse, the displacement of the major subtropical gyres is causing the nutrient-poor regions to expand, reducing the productivity of the ocean as a whole. Accordingly, the shift in the gyres could represent the beginning of a fundamental change in the ocean, according to the study’s authors.

###

AGU (www.agu.org) is an international association of more than 60,000 advocates and experts in Earth and space science. Through our initiatives, such as mentoring, professional development and awards, AGU members uphold and foster an inclusive and diverse scientific community. AGU also hosts numerous conferences, including the largest international Earth and space science meeting as well as serving as the leading publisher of the highest quality journals. Fundamental to our mission since our founding in 1919 is to live our values, which we do through our net zero energy building in Washington, D.C. and making the scientific discoveries and research accessible and engaging to all to help protect society and prepare global citizens for the challenges and opportunities ahead.

*****

Notes for Journalists

This paper is freely available. Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) can download a PDF copy of the article by clicking on this link: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2019GL085868

Journalists and PIOs may also request a copy of the final paper by emailing Nanci Bompey at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Poleward shift of the major ocean gyres detected in a warming climate”

Authors:

Hu Yang, Gerrit Lohmann, Uta Krebs-Kanzow, Monica Ionita, Xiaoxu Shi, Dmitry Sidorenko, Xun Gong: Climate Sciences, Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany;

Xueen Chen: College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China;

Evan J. Gowan: Climate Sciences, Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany.

Contact information for the researchers:

Gerrit Lohmann, AWI

+49 (0) 471 4831 1758

[email protected]

Hu Yang, AWI

+49 (0) 471 4831 1897

[email protected]

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

[email protected]

AWI press contact:

Ulrike Windhövel

+49 (0) 471 4831 2008

[email protected]