3 May 2013

WASHINGTON — Global warming may increase the risk for extreme rainfall and drought, according to a new modeling study. The research shows for the first time how rising carbon dioxide concentrations could affect the entire range of rainfall types on Earth.

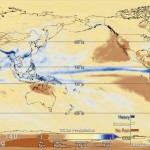

Model simulations spanning 140 years show that warming from carbon dioxide will change the frequency at which regions around the planet receive no rain (brown), moderate rain (tan), and very heavy rain (blue). The occurrence of no rain and heavy rain will increase, while moderate rainfall will decrease. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio

Analysis of computer simulations from 14 climate models indicates that wet regions of the world, such as the equatorial Pacific Ocean and Asian monsoon regions, will see increases in heavy precipitation because of warming resulting from projected increases in carbon dioxide levels. Arid land areas outside the tropics and many regions with moderate rainfall could become drier.

The analysis provides a new assessment of global warming’s impacts on precipitation patterns around the world. The study was accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

“In response to carbon dioxide-induced warming, the global water cycle undergoes a gigantic competition for moisture resulting in a global pattern of increased heavy rain, decreased moderate rain, and prolonged droughts in certain regions,” said William Lau of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., who is lead author of the study.

The models project that, for every 0.56 degrees Celsius (1 degree Fahrenheit) of carbon dioxide-induced warming, heavy rainfall will increase globally by 3.9 percent and light rain will increase globally by 1 percent. However, total global rainfall is not projected to change much because moderate rainfall will decrease globally by 1.4 percent.

Focusing their analysis on three types of rainfall, the study authors define heavy rainfall as monthly average precipitation greater than 9 millimeters (0.35 inch) per day. Light rain means a monthly average below 0.3 mm (0.01 of an inch) per day. Between those lies moderate rainfall, defined as a monthly average in the range 0.9mm.- 2.4 mm. (0.04 – 0.09 in.) per day.

Areas projected to see the most significant increase in heavy rainfall are in the tropical zones around the equator, particularly in the Pacific Ocean and Asian monsoon regions.

Some regions outside the tropics may have no rainfall at all. The models also projected for every 0.56 degrees Celsius (1 degree Fahrenheit) of warming, the length of periods with no rain will increase globally by 2.6 percent. In the Northern Hemisphere, areas most likely to be affected include the deserts and arid regions of the southwest United States, Mexico, North Africa, the Middle East, Pakistan, and northwestern China. In the Southern Hemisphere, drought becomes more likely in South Africa, northwestern Australia, coastal Central America and northeastern Brazil.

“Large changes in moderate rainfall, as well as prolonged no-rain events, can have the most impact on society because they occur in regions where most people live,” Lau said. “Ironically, the regions of heavier rainfall, except for the Asian monsoon, may have the smallest societal impact because they usually occur over the ocean.”

Lau and colleagues based their analysis on the outputs of 14 climate models in simulations of 140-year periods. The simulations began with carbon dioxide concentrations at about 280 parts per million — similar to pre-industrial levels and well below the current level of almost 400 parts per million — and then increased by 1 percent per year. The rate of increase is consistent with a “business as usual” trajectory of the greenhouse gas as described by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Analyzing the model results, Lau and his co-authors calculated statistics on the rainfall responses for a 27-year control period at the beginning of the simulation, and also for 27-year periods around the time of doubling and tripling of carbon dioxide concentrations.

The model predictions of how much rain will fall at any one location as the climate warms are not very reliable, the authors conclude. “But if we look at the entire spectrum of rainfall types we see all the models agree in a very fundamental way — projecting more heavy rain, less moderate rain events, and prolonged droughts,” Lau said.

Joint Release

AGU Contact:

Peter Weiss, +1 (202) 777-7507, [email protected]

NASA Contacts:

Steve Cole, Headquarters, Washington, D.C., 202-358-0918, [email protected]

Kathryn Hansen, Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md., 301-286-1046, [email protected]

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of this accepted article by clicking on this link:http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/grl.50420/abstract

Or, you may order a copy of the paper by emailing your request to Peter Weiss at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release are under embargo.

Visualisation:

An animation accompanies the NASA version of this release at http://go.usa.gov/TQM3.

“A canonical response of precipitation characteristics to Global Warming from CMIP5 models”

William K.-M. Lau

Laboratory for Atmospheres, NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA;H.-T. WuScience Systems and Applications, Inc., Lanham, Maryland, USA;

K.-M. KimMorgan State University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA;

Dr. William K.-M. Lau: office phone: +1 (301) 614-6332, email: [email protected]