Previously unstudied data from a seismic wave, detected 750 kilometers from the seamount, may bolster tsunami early-warning systems.

4 November 2024

The origins of the massive January 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcanic eruption may have been detected in a seismic wave recorded 750 kilometers from the volcano, according to new research in Geophysical Research Letters. Credit: NASA

Researcher contact information:

Mie Ichihara, University of Tokyo, [email protected], (UTC+9 hours)

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, [email protected] (UTC-5 hours)

WASHINGTON — Fifteen minutes before the massive January 2022 eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano, a seismic wave was recorded by two distant seismic stations. Now, researchers argue that similar early signals could be used to warn of other impending eruptions in remote oceanic volcanoes.

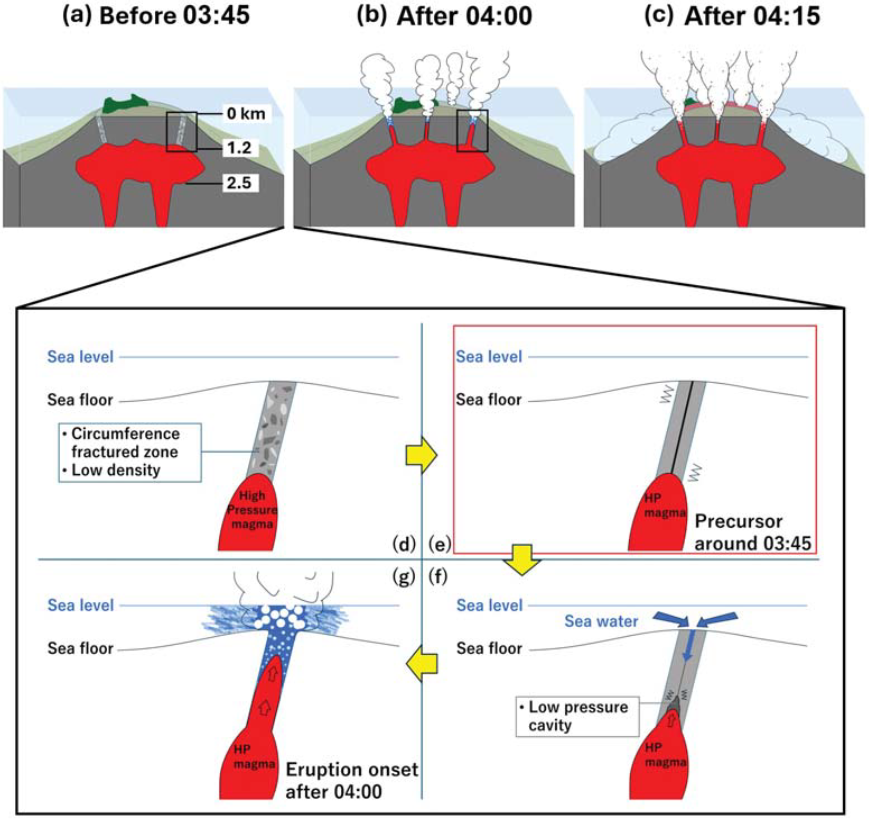

The researchers propose that the seismic wave was caused by a fracture in a weak area of oceanic crust beneath the volcano’s caldera wall. That fracture allowed seawater and magma to pour into and mix together in the space above the volcano’s subsurface magma chamber, explosively kickstarting the eruption.

The research was published in Geophysical Research Letters, an open-access AGU journal that publishes high-impact, short-format reports with immediate implications spanning all Earth and space sciences.

The results build on the researchers’ previous work monitoring remote volcanoes. In this case, the Rayleigh wave, a type of seismic wave that moves through the Earth’s surface, was detected 750 kilometers (approximately 466 miles) from the volcano.

“Early warnings are very important for disaster mitigation,” said Mie Ichihara, a volcanologist at the University of Tokyo and one of the study’s coauthors. “Island volcanoes can generate tsunamis, which are a significant hazard.”

Silent precursor to a violent eruption

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai is an oceanic volcano in the western Pacific Ocean in the Kingdom of Tonga. The seamount was created by the subduction of the Pacific Plate underneath the Australian Plate, a process that generates magma and leads to eruptions.

On January 15, 2022, the volcano erupted with record-breaking energy, injecting 58,000 Olympic swimming pools of water vapor into the stratosphere, setting off an unprecedented lightning storm and generating a tsunami. That massive eruption was preceded by a smaller eruption on January 14 and, before that, a month of eruptive activity.

Researchers still debate the exact start time of the eruption, though most agree that the eruption started shortly after 4:00 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). The new study reports a Rayleigh wave that started around 3:45 UTC.

The researchers used seismic data to analyze the Rayleigh wave, which was detected by instruments, but not felt by humans, at seismic stations on the islands of Fiji and Futuna. While Rayleigh waves are a common feature of volcanic eruptions and earthquakes, the researchers believe that this wave signified a precursor event and possible cause of the massive eruption.

“Many eruptions are preceded by seismic activity,” said Takuro Horiuchi, a volcanology graduate student at the University of Tokyo and the lead author of the study. “However, such seismic signals are subtle and only detected within several kilometers of the volcano.”

In contrast, this seismic signal traveled a great distance, indicating a huge seismic event. “We believe unusually large movements started at the time of the precursor,” Horiuchi said.

The eruption may have been triggered by a crack in a weak area of the ocean’s crust, which let seawater and magma explosively mix below the rim of the caldera, according to the new research. Credit: Takuro Horiuchi

Secrets of the seamount

Scientists may never know exactly what caused the gigantic, “caldera-forming” eruption, but Ichihara believes that the process was not instantaneous. Instead, she thinks that this precursor event was the start of an underground process that ultimately led to the eruption.

But it can be difficult to nail down the origins of these rare, colossal eruptions.

“There are very few observed caldera-forming eruptions, and there are even fewer witnessed caldera-forming eruptions in the ocean,” Ichihara said. “This gives one scenario about the processes leading to caldera formation, but I wouldn’t say that this is the only scenario.”

Regardless, detecting early eruption signals may give island nations and coastal areas more valuable time to prepare when faced with imminent tsunamis — even when the signal cannot be felt on the surface.

“At the time of the eruption, we didn’t think of using this kind of analysis in real-time,” Ichihara said. “But maybe the next time that there is a significant eruption underwater, local observatories can recognize it from their data.”

Notes for Journalists:

This study is published in Geophysical Research Letters with open access. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo. View and download a pdf of the study.

Paper title:

“A seismic precursor 15 minutes before the giant eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano on January 15, 2022”

Authors:

- Takuro Horiuchi, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- Mie Ichihara, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- Kiwamu Nishida, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

- Takayuki Kaneko, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Contributed by Madeline Reinsel