19 April 2022

Glaciers atop Hurricane Ridge in the Olympic Mountains. Climate change poses a heightened risk to these relatively low-elevation glaciers, as highlighted by a new study in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface.

Credit: Kentaro Toma/Unsplash

AGU press contact:

Rebecca Dzombak, +1 (202 777-7492), [email protected] (UTC-4 hours)

Portland State University press contact:

Katy Swordfisk, [email protected] (UTC-7 hours)

Contact information for the researchers:

Andrew Fountain, [email protected] (UTC-7 hours)

WASHINGTON—By 2070, the glaciers on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State will have largely disappeared, according to a new study. The loss will alter the region’s ecosystems and shrink a critical source of summer water for local communities.

The Olympic Mountains, which range from sea level to just under 8000 feet in elevation, are almost entirely within the bounds of Olympic National Park on the western peninsula of Washington state. The park hosts approximately 200 glaciers and in recent years typically receives well over 100 inches of precipitation, much of which falls as snow. But as the climate warms, these low-elevation mountains and their glaciers are threatened.

The new study was published in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research Earth Surface, which publishes research on the processes affecting the form and function of Earth’s surface.

Since about 1900, the Olympic Peninsula has lost half of its glacier area and since 1980, 35 glaciers and 16 perennial snowfields have disappeared. Nearly all the glaciers on the peninsula are located within Olympic National Park and are otherwise on surrounding state lands. The few remaining glaciers will likely be shells of their former selves, said Andrew Fountain, professor of geology and geography at Portland State University who led the study.

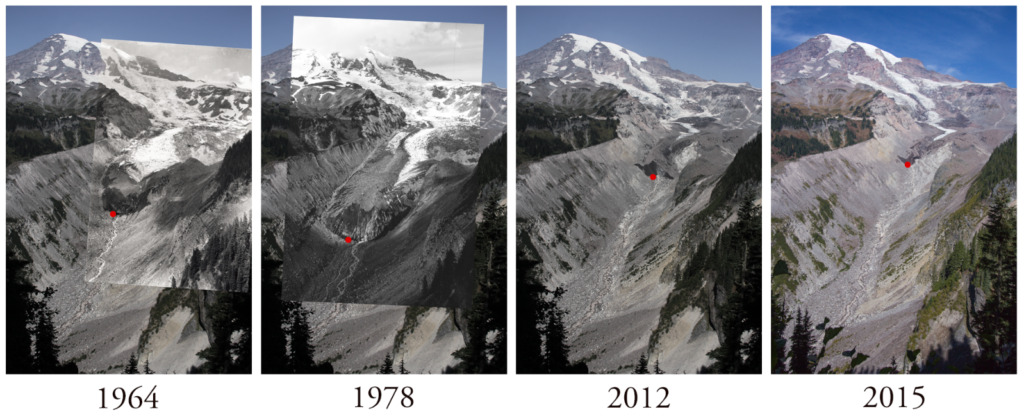

The shrinking of Nisqually Glacier, Mount Rainier, Washington. Credit: 1964 – F.M Veatch, US Geological Survey; 1978- D.R. Crandell, US Geological Survey; 2012, 2015- Hassan Basagic.

“There’s little we can do to prevent the disappearance of these glaciers,” said Fountain. “We’re on this global warming train right now. Even if we’re super good citizens and stop adding carbon dioxide in the atmosphere immediately, it will still be 100 years or so before the climate responds.”

Even though preventing climate change-driven glacier disappearances is not likely, ensuring things don’t get worse is a critical goal, Fountain said.

“This is yet another tangible call for us to take climate change seriously and take actions to minimize our climate impact,” he added.

“The rapid, long-term loss of glacial mass that the authors have detected is a strong indication, uncontaminated by local human effects, of a warming global climate. This is a clear and compelling signal of changes that are rolling out across many North American landscapes,” said Dan Cayan, a climate scientist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography who was not involved in the study. “It is regrettable that the Olympic glaciers are very likely to melt away as climate warming over the coming decades runs its course.”

U.S. Geological Survey data show a similar decline of glacier ice in the North Cascades of Washington, farther inland in Glacier National Park, Montana and farther north in Alaska, according to USGS Research Physical Scientist Caitlyn Florentine. The new study highlights glaciers’ vulnerability to warmer temperatures in both summer, which increase glacial melt, and winter, which decrease glacial growth, said Florentine.

“This double whammy has downstream implications for glacier-adapted ecosystems in the U.S. Pacific Northwest,” said Florentine.

Glacier disappearances will trigger a chain of impacts, beginning with diminishing alpine streams and species like bull trout that have adapted to those cold waters. Negative impacts can ripple throughout ecosystems and up food webs.

“Once you lose your seasonal snow, the only source of water in these alpine areas is glacier melt. And without the glaciers, you’re not going to have that melt contributing to the stream flow, therefore impacting the ecology in alpine areas,” Fountain said. “That’s a big deal with disastrous fallout.”

The Olympic glaciers are particularly vulnerable to climate change because of their low elevation as compared to glaciers elsewhere at higher elevations where temperatures are significantly cooler such as the Cascade Mountains of Oregon and Washington.

“As the temperatures warm, not only will the glaciers melt more in summer, which you’d expect, but in the wintertime, it changes the phase of the precipitation from snow to rain,” he said. “So the glaciers get less nourished in the winter, more melt in the summer, and then they just fall off the map.”

This press release is published jointly with Portland State University.

###

AGU (www.agu.org) supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists:

This research study will be available for free until 5/15. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

“Glaciers of the Olympic Mountains, Washington – the past and future 100 years”

Author information:

- Andrew G. Fountain (corresponding author), Christina Gray, Bryce Glenn, Department of Geology, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon, USA

- Brian Menounos, Geography Program, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, British Columbia, Canada

- Justin Pflug, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, USA

- Jon L. Riedel, US National Park Service, North Cascades National Park, Sedro-Woolley, Washington, USA