New analysis provides detailed blueprint for the U.S. to become carbon neutral by 2050

27 January 2021

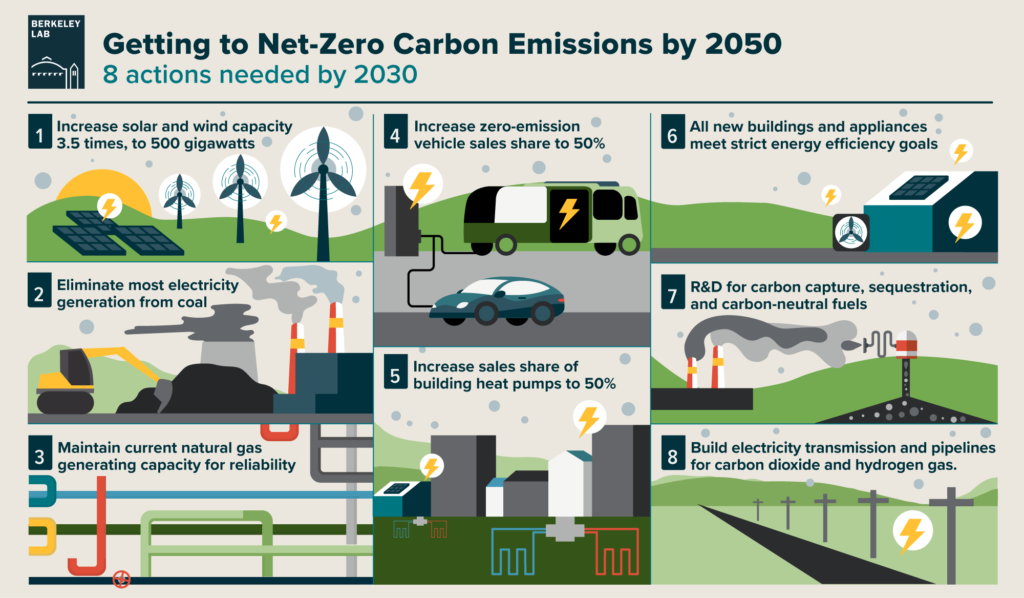

This infographic details the way in which the U.S. can reach carbon neutrality by mid-century.

Credit: Jenny Nuss/Lawrence Berkeley National Lab.

AGU press contact:

Lauren Lipuma, +1 (202) 777-7396, [email protected] (GMT-5)

Contact information for the researchers:

James Williams, University of San Francisco, [email protected] (GMT-8)

Margaret S. Torn, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, [email protected] (GMT-8)

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory press contact:

Julie Chao, +1 (510) 486-6491, [email protected] (GMT-8)

WASHINGTON—Reaching zero net emissions of carbon dioxide from energy and industry by 2050 can be accomplished by rebuilding U.S. energy infrastructure to run primarily on renewable energy, at a net cost of about $1 per person per day, according to new research.

In a new study in AGU Advances, which publishes high-impact, open-access research and commentary across the Earth and space sciences, researchers created the first published roadmap specifying how to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world must reach zero net carbon dioxide emissions by mid-century to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and avoid the most dangerous impacts of climate change.

The researchers found the U.S. can reach zero net carbon emissions by mid-century by methodically increasing energy efficiency, switching to electric technologies, using clean electricity (especially wind and solar power) and deploying a small amount of carbon capture technology.

The pathways studied have net costs ranging from 0.2% to 1.2% of GDP, with higher costs resulting from certain tradeoffs, such as limiting the amount of land given to solar and wind farms.

“We were pleasantly surprised that the cost of the transformation is lower now than in similar studies we did five years ago, even though this achieves much more ambitious carbon reduction,” said Margaret Torn, a senior scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and senior author of the new study. “The main reason is that the cost of wind and solar power and batteries for electric vehicles have declined faster than expected.”

Transforming infrastructure

In the new study, researchers developed multiple feasible technology pathways that differ widely in remaining fossil fuel use, land use, consumer adoption, nuclear energy, and bio-based fuels use but share a key set of strategies.

“The decarbonization of the U.S. energy system is fundamentally an infrastructure transformation,” Torn said. “It means that by 2050 we need to build many gigawatts of wind and solar power plants, new transmission lines, a fleet of electric cars and light trucks, millions of heat pumps to replace conventional furnaces and water heaters, and more energy-efficient buildings – while continuing to research and innovate new technologies.”

In this transition, very little infrastructure would need “early retirement,” or replacement before the end of its economic life. “No one is asking consumers to switch out their brand-new car for an electric vehicle,” Torn said. “The point is that efficient, low-carbon technologies need to be used when it comes time to replace the current equipment.”

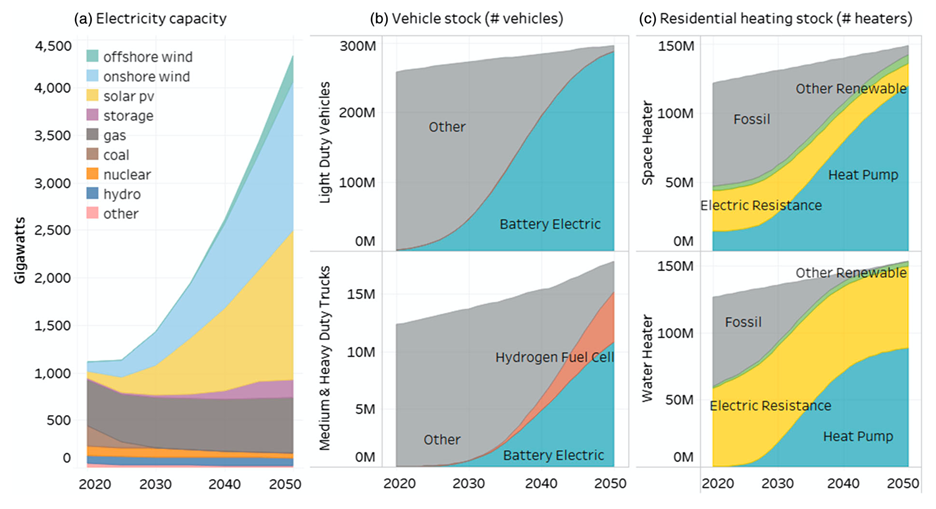

In the least-cost scenario to achieve net zero emissions of carbon dioxide by 2050, wind, solar, and battery storage capacity will have to increase several-fold (left chart). Vehicles will need to be mostly electric, powered either by batteries or fuel cells (middle charts). Residential space and water heaters will also need to be electrified, powered either by heat pumps or electric heaters (right charts).

Credit: Williams et al/AGU Advances/AGU.

The economic costs of the scenarios are almost exclusively capital costs from building new infrastructure. But Torn points out there is an economic upside to that spending.

“All that infrastructure build equates to jobs, and potentially jobs in the U.S., as opposed to sending money overseas to buy oil from other countries,” she said. “There’s no question that there will need to be a well-thought-out economic transition strategy for fossil fuel-based industries and communities, but there’s also no question that there are a lot of jobs in building a low-carbon economy.”

The cost figures would be lower still if they included the economic and climate benefits of decarbonizing our energy systems. For example, less reliance on oil will mean less money spent on oil and less economic uncertainty due to oil price fluctuations. Climate benefits include the avoided impacts of climate change, such as extreme droughts and hurricanes, avoided air and water pollution from fossil fuel combustion, and improved public health.

###

AGU (www.agu.org) supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists

This research study is open access. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

“Carbon-Neutral Pathways for the United States”

Authors:

James H. Williams: Energy Systems Management, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, United States; Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project, Sustainable Development Solutions Network, New York, New York, United States;

Ryan A. Jones, Ben Haley, Gabe Kwok, Jeremy Hargreaves, Jamil Farbes: Evolved Energy Research, San Francisco, California, United States;

Margaret S. Torn: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, California, United States; Energy and Resources Group, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States.