7 September 2017

Lightning near an aircraft carrier in the Strait of Malacca. New research finds lightning strokes occurred nearly twice as often directly above heavily-trafficked shipping lanes in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea year-round from 2005 through 2016.

Credit: pxhere.com; public domain.

WASHINGTON D.C. — Thunderstorms directly above two of the world’s busiest shipping lanes are significantly more powerful than storms in areas of the ocean where ships don’t travel, according to new research.

A new study mapping lightning around the globe finds lightning strokes occur nearly twice as often directly above heavily-trafficked shipping lanes in the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea than they do in areas of the ocean adjacent to shipping lanes that have similar climates.

The difference in lightning activity can’t be explained by changes in the weather, according to the study’s authors, who conclude that aerosol particles emitted in ship exhaust are changing how storm clouds form over the ocean.

The new study is the first to show ship exhaust can alter thunderstorm intensity. The researchers conclude that particles from ship exhaust make cloud droplets smaller, lifting them higher in the atmosphere. This creates more ice particles and leads to more lightning.

The results provide some of the first evidence that humans are changing cloud formation on a nearly continual basis, rather than after a specific incident like a wildfire, according to the authors. Cloud formation can affect rainfall patterns and alter climate by changing how much sunlight clouds reflect to space.

“It’s one of the clearest examples of how humans are actually changing the intensity of storm processes on Earth through the emission of particulates from combustion,” said Joel Thornton, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle and lead author of the new study in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

“It is the first time we have, literally, a smoking gun, showing over pristine ocean areas that the lightning amount is more than doubling,” said Daniel Rosenfeld, an atmospheric scientist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem who was not connected to the study. “The study shows, highly unambiguously, the relationship between anthropogenic emissions – in this case, from diesel engines – on deep convective clouds.”

Mapping lightning and exhaust

All combustion engines emit exhaust, which contains microscopic particles of soot and compounds of nitrogen and sulfur. These particles, known as aerosols, form the smog and haze typical of large cities. They also act as cloud condensation nuclei – the seeds on which clouds form. Water vapor condenses around aerosols in the atmosphere, creating droplets that make up clouds.

Cargo ships crossing oceans emit exhaust continuously and scientists can use ship exhaust to better understand how aerosols affect cloud formation.

A map of ships crossing the Indian Ocean and surrounding seas during June 2012. Most ships crossing the northern Indian Ocean follow a narrow, nearly straight track around 6 degrees North between Sri Lanka and the island of Sumatra. East of Sumatra, ships travel southeast through the Strait of Malacca, rounding Singapore and extending northeast across the South China Sea. Aerosol particle emissions in these shipping lanes are ten times or more greater than in other shipping lanes in the region, and are among the largest globally.

Credit: Shipmap.org, an interactive map of commercial shipping movements, created by Kiln for University College London’s Energy Institute.

In the new study, co-author Katrina Virts, an atmospheric scientist at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, was analyzing data from the World Wide Lightning Location Network, a network of sensors that locates lightning strokes all over the globe, when she noticed a nearly straight line of lightning strokes across the Indian Ocean.

Virts and her colleagues compared the lightning location data to maps of ships’ exhaust plumes from a global database of ship emissions. Looking at the locations of 1.5 billion lightning strokes from 2005 to 2016, the team found nearly twice as many lightning strokes on average over major routes ships take across the northern Indian Ocean, through the Strait of Malacca and into the South China Sea, compared to adjacent areas of the ocean that have similar climates.

More than $5 trillion of world trade passes through the South China Sea every year and nearly 100,000 ships pass through the Strait of Malacca alone. Lightning is a measure of storm intensity, and the researchers detected the uptick in lightning at least as far back as 2005.

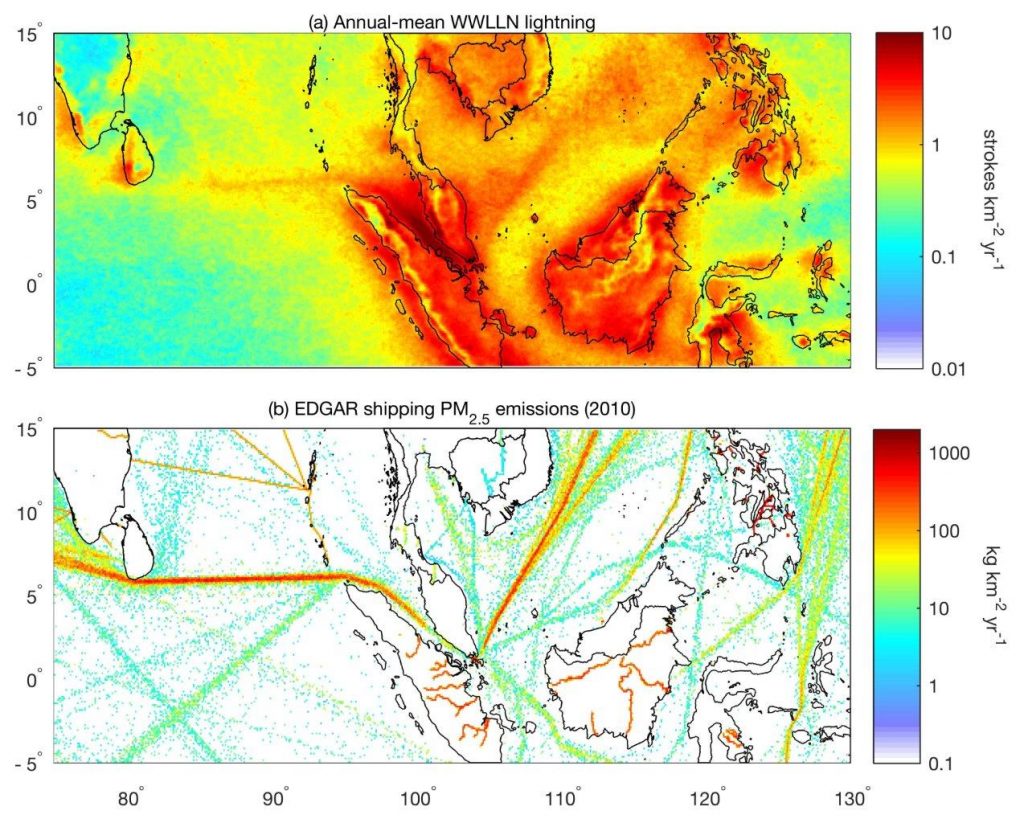

The top map shows annual average lightning density at a resolution of about 10 kilometers (6 miles), as recorded by the WWLLN, from 2005 to 2016. The bottom map shows aerosol emissions from ships crossing routes in the Indian Ocean and South China sea from 2010.

Credit: Thornton et al/Geophysical Research Letters/AGU.

“All we had to do was make a map of where the lightning was enhanced and a map of where the ships are travelling and it was pretty obvious just from the co-location of both of those that the ships were somehow involved in enhancing lightning,” Thornton said.

Forming cloud seeds

Water molecules need aerosols to condense into clouds. Where the atmosphere has few aerosol particles – over the ocean, for instance – water molecules have fewer particles to condense around, so cloud droplets are large.

When more aerosols are added to the air, like from ship exhaust, water molecules have more particles to collect around. More cloud droplets form, but they are smaller. Being lighter, these smaller droplets travel higher into the atmosphere and more of them reach the freezing line, creating more ice, which creates more lightning. Storm clouds become electrified when ice particles collide with each other and with unfrozen droplets in the cloud. Lightning is the atmosphere’s way of neutralizing that built-up electric charge.

Ships burn dirtier fuels in the open ocean away from port, spewing more aerosols and creating even more lightning, Thornton said.

“I think it’s a really exciting study because it’s the most solid evidence I’ve seen that aerosol emissions can affect deep convective clouds and intensify them and increase their electrification,” said Steven Sherwood, an atmospheric scientist at the University of New South Wales in Sydney who was not connected to the study.

“We’re emitting a lot of stuff into the atmosphere, including a lot of air pollution, particulate matter, and we don’t know what it’s doing to clouds,” Sherwood said. “That’s been a huge uncertainty for a long time. This study doesn’t resolve that, but it gives us a foot in the door to be able to test our understanding in a way that will move us a step closer to resolving some of those bigger questions about what some of the general impacts are of our emissions on clouds.”

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing 60,000 members in 137 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

Notes for Journalists

This research article is open access for 30 days. A PDF copy of the article can be downloaded at the following link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2017GL074982/pdf.

Journalists and PIOs may also order a copy of the final paper by emailing a request to Nanci Bompey at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Lightning Enhancement Over Major Shipping Lanes”

Authors:

Joel A. Thornton: Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, U.S.A.;

Katrina S. Virts: NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Alabama, U.S.A.;

Robert H. Holzworth: Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, U.S.A.;

Todd P. Mitchell: Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, U.S.A.

Contact information for the authors:

Joel Thornton: [email protected], +1 (206) 962-1430.

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

[email protected]

University of Washington Press Contact:

Hannah Hickey

+1 (206) 543-2580

[email protected]