Milder winter temperatures reduce the risk of death from cold, but heat waves take more lives in summers. In the U.S., gains and losses caused by global warming will be roughly equal until temperatures rise 3 degrees Celsius above preindustrial averages, when heat will begin to take a greater toll, a new study finds.

7 September 2023

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, [email protected]

Contact information for the researchers:

Andrew Dessler, Texas A&M University, [email protected]

Jangho Lee, University of Chicago, [email protected]

- With up to 3 degrees Celsius of warming, lives saved from warmer winters balance lives lost to rising heat, even with little heat adaptation.

- But past 3 degrees of warming, heat-related deaths rise quickly, outnumbering the lives saved by warmer winters.

- Adapting cities for heat by deploying widespread AC access, especially northern U.S. cities, could reduce the trend and save lives.

- The ongoing demographic shift to an older population, at higher risk from dangerous temperatures, will lead to a large increase in the number of temperature-related deaths.

WASHINGTON — If global temperatures warm 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) above preindustrial averages and cities do not expand existing cooling infrastructure, the United States can expect five times the number of temperature-related deaths per year, a new study finds. Adapting cities to heat, primarily through greatly expanded access to air conditioning in the northern states, could slow that trend by 28%.

Population growth and the expanding share of the population age 75 and older drives most of the increase in number of deaths from heat and cold, according to the study, published this week in GeoHealth, AGU’s journal investigating the intersection of human and planetary health for a sustainable future. People over the age of 75 are ten times more vulnerable to heat and cold than younger adults, according the researchers, so as the U.S. population ages, a larger proportion of residents will be at risk.

The effects of climate change alone contribute little to the overall loss of life from temperature-related health impacts in the United States as a whole — until the 3-degree threshold is crossed.

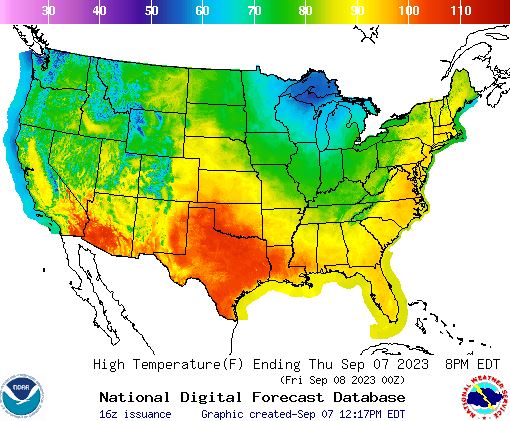

“We find that in the future, temperature-related deaths are going to increase in the northern U.S., mostly due to an increase in heat-related deaths,” said Jangho Lee, a climate scientist at the University of Illinois and lead author of the study. “That’s because southern cities, like Phoenix or Houston, are already very well adapted to heat, whereas northern cities are not.”

Warmer winters are reducing the number of cold-related deaths, but rising mortality due to excessive heat is offsetting the lives saved. The study predicted this balance will continue until global temperature averages cross 3 degrees Celsius of warming, an inflection point when heat-related deaths can be expected to rise rapidly, causing overall temperature-related deaths to rise.

If current carbon emissions continue unchecked, that temperature tipping point could be reached by the end of the century.

“Because cold kills more people in the U.S. than heat, some people argue that climate change will save more lives from fewer cold temperatures than we will lose from more hot temperatures,” said Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University and an author of the new study. “But that’s not what we found. It’s not going to save a lot of lives. It’s basically a wash in the in the U.S., up until about 3 degrees warming, and then it depends on your level of adaptation.”

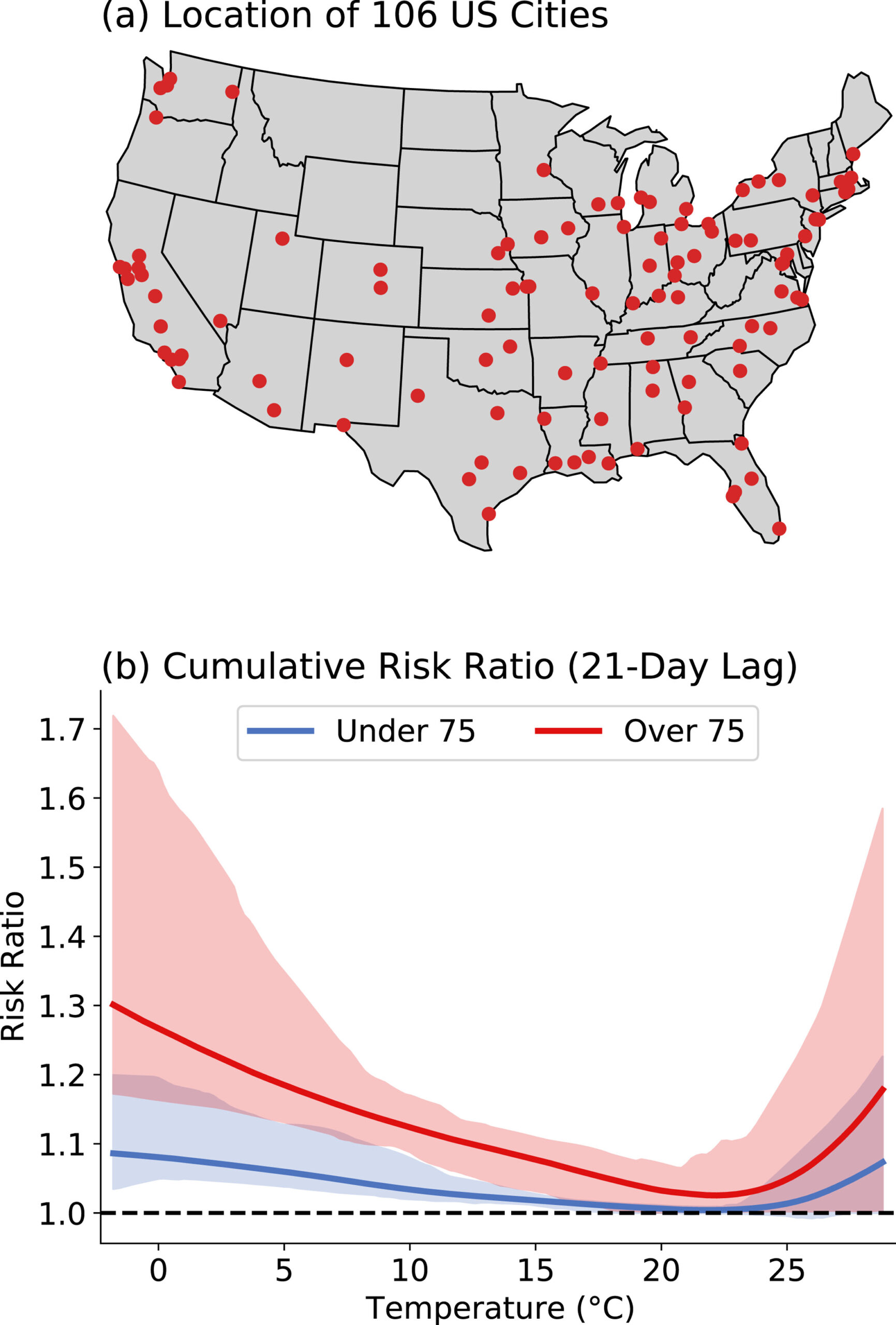

The study drew on data from 106 U.S. cities, about 65% of the U.S. population, from 1987 to 2000, finding on average 36,444 temperature-related deaths per year: 4,819 from heat and 31,625 (85%) from cold. About 75% of people who succumbed to either heat or cold were over the age of 75, a group which made up only 5% of the population over the study period.

The study projected that without adaptation to heat, the combination of warming climate and an increasing and aging population would cause temperature-related deaths in these cities to reach 200,000 per year at 3 degrees Celsius of global average warming. Adaptation across the United States to the same extent as the most heat-ready cities could reduce this toll by 28%, to 144,000.

The danger of exposure to hot and cold temperatures rises steeply with age. Mortality data from 106 U.S. cities (top) informed the relative risk of temperature-related death, averaged across all cities (bottom). The blue curve marks the risk ratio for people under 75 years of age and the red curve the risk ratio for adults over 75 years. The risk ratio is the number of deaths at each temperature divided by the number of deaths at the curve minimum — the temperature at which the fewest deaths occur. This safest temperature is around 22 degrees Celsius (71.6 degrees Fahrenheit). Shaded regions show the 5th percentile to 95th percentile range of the risk ratio curve for all cities.

Credit: Lee and Dessler (2023) GeoHealth https://doi.org/10.1029/2023GH000799

Surprisingly, most cold-related deaths occur in relatively mild temperatures, well above freezing and in many cases only 5 degrees Celsius (9 degrees Fahrenheit) below ideal conditions, which is 22 degrees Celsius (72 degrees Fahrenheit) in most locations. Heat-related deaths, in contrast, are more strongly associated with extreme heat events.

The study predicts decreases in exposure to moderately cold temperatures will save the most lives in a warming climate. At the same time, extreme temperatures responsible for the greatest increase in mortality were predicted to have a minor impact in southern cities, where most residents already have access to some air conditioning. The combination pushes the burden of lives lost to the north.

North Midwestern cities Minneapolis, Milwaukee and Muskegon, Michigan, are expected to experience the biggest temperatures jumps of the cities included in the study (0.96, 0.88 and 0.86 degrees larger than the global average respectively).

“We cannot really project how people will adapt in the future. We don’t know how policies are going to change, we don’t know how much money we’re going to spend. So we come up came up with two limiting scenarios of adaptation. One is no adaptation at all, and one another is the full adaptation,” Lee said. Full adaptation, he explained, means warmer future cities would adopt the cooling infrastructure of more southern locations that experience similar temperature ranges now.

Dessler cautions the situation in the United States, a wealthy country with perhaps the highest capacity in the world to buy temperature relief, cannot be extrapolated everywhere. In the tropics, death from cold is uncommon, he said, and many countries are already struggling to manage current temperatures. These regions will not see benefits, only rising heat stress.

“Air conditioning is expensive,” Dessler said. “People who don’t have it today or live in an under-air-conditioned world where they can only run the air conditioner for an hour or two — it’s going to be hard for them to adapt.”

###

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists:

GeoHealth is open access. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

“Future Temperature-Related Deaths in the U.S.: The Impact of Climate Change, Demographics, and Adaptation”

Authors:

- Jangho Lee, (corresponding author) University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

- Andrew Dessler, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA