4 March 2010

WASHINGTON—Contrary to prevailing wisdom, the takeover of rangelands by trees and shrubs can increase flows of streams and recharging of groundwater, a new study shows. The soon-to-be published analysis of many decades of historical records for four central Texas river basins challenges widespread perceptions that woody plants have the opposite effects on streams and aquifers.

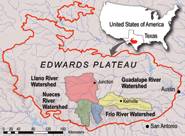

Long-term streamflow patterns have been evaluated in four river basins of Edwards Plateau of Central Texas. The basins range in size from 600 to 3000 square kilometers. In each of the basins, the contribution from springs to river flows have doubled since 1960.

CREDIT: American Geophysical Union

[ High-resolution image 1.3MB]

Large numbers of cattle, sheep, and goats that continuously grazed the area’s rangelands led to widespread soil degradation, partly hindering the amount of water recharging springs and groundwater, says hydrologist Bradford Wilcox of Texas A&M University and Texas AgriLife Research, in College Station, Texas.

He and Yun Huang, a former graduate student at Texas A&M, will publish their results in an upcoming issue ofGeophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

From 1880 to 1900, there were more animals on the land than it could support, Wilcox says. For a short period of time near the turn of the last century, stocking rates were 10 times greater than current levels. Since the late 1900s, however, as fewer cattle and other livestock were used on the land for agricultural production, the region has gone through revitalization.

“As a result, these landscapes are recovering, but they’ve also converted to woody plants,” Wilcox notes. “We’re also seeing large-scale increases in the amount of spring flows. This is opposite of what everybody is presuming —[which is that] the trees are there sucking up all of this water. The trees are actually allowing the water to infiltrate.”

In fact, spring flows are twice as high as they were prior to 1950, he adds.

“This area was basically converted from grassland to shrubland after many years of heavy livestock grazing. What people have forgotten is that in the time period between healthy grasslands and the current shrublands, there was an extended period when the land was quite degraded. Subsequent to 1960, livestock numbers have declined and the landscape has recovered although there are now more cedar than in the past,” Wilcox explains.

In the new study, he and Huang, who is now with LBG Guyton, in Austin, assess the hydrological changes that have taken place in the region as patterns of land use and vegetation changed. To do so, the researchers analyzed annual measurements dating back to 1925, or earlier, for the Nueces, Frio, Guadulupe, and Llano rivers. The measurements provide an annual record of ‘baseflow,’ or flow derived from groundwater only (i.e. springs) and of ‘stormflow’ or flow resulting from rainfall, for those rivers.

The scientists report that the total flow in the three of the four rivers has gone up in recent decades, “largely because contributions in the form of baseflow have increased.” The baseflow of the fourth river also increased, although its total flow did not. Yet, rainfall in the region hasn’t changed significantly.

Although the prevailing wisdom has been that proliferation of woody plants stifles infiltration of water back into aquifers, the new results suggest otherwise. Moreover, the results have implications beyond the Edwards Plateau, Wilcox and Huang maintain, applying in general to “semiarid and subhumid rangelands in which springs and intermittent or perennial streams are found.” For such regions, the transition to woody plants appears to be good news for regional water resources.

Circa 1940: Degraded rangelands in Edwards Plateau.

CREDIT: Charles Taylor and American Geophysical Union

[ High-resolution image 90KB]

Same location in Edwards Plateau, 1993. The picture highlights the improvement in condition seen for much of the Plateau since 1960.

CREDIT: Charles Taylor and American Geophysical Union

[ High-resolution image 377KB]

Joint Release American Geophysical Union and Texas A&M University

Blair Fannin, +1 (979) 845-2259, [email protected]

As of the date of this press release, this study by Wilcox and Huang is still “in press” (i.e. not yet published). Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of this manuscript.

You may order a copy of the paper in press by emailing your request to Peter Weiss at [email protected] or Blair Fannin at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release are under embargo.

“Woody Plant Encroachment Paradox: Rivers Rebound as Degraded Grasslands Convert to Woodlands”

Bradford P. Wilcox

and Yun Huang

Ecosystem Science and Management, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA

Brad Wilcox, Professor

Department of Ecosystems Science and Management, 979-458-1899, [email protected]