Recent policies and funding have left the delta’s biodiverse wetlands without restoration support. One researcher says there’s good evidence to bolster management efforts for maximum preservation

18 February 2024

This drone image shows the last 4 miles (6 kilometers) of Loomis Pass, a constructed channel that branches several times along its path from the Mississippi River. The foreground shows approximately 50 acres (20 hectares) of emergent and shallow-water wetlands that were created and are being maintained by the Loomis Pass restoration channel. (Credit: Gabe Griffen)

OSM press contact:

Liza Lester, [email protected] (UTC-5 hours)

Contact information for the researcher:

John Andrew Nyman, Louisiana State University Agricultural Center, [email protected] (UTC-6 hours)

NEW ORLEANS — The Bird’s Foot Delta, a famous expanse of wetlands and navigation channels off the Louisiana coast, is an important transportation hub, moving fossil fuels and agricultural products to a global market. It also supports a biodiverse ecosystem for wetland-dependent fish and migratory birds. But support for wetland restoration projects has faltered in recent years, putting the delta’s future in question.

Many of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands, including those in Bird’s Foot, have been subsiding and disappearing because of several natural and human-induced changes such as sea-level rise and dams that starve the wetlands of sediment replenishment. For decades, federal and state agencies have tried to mitigate losses by funding projects to maintain Bird’s Foot wetlands. But those efforts may not be fully funded in the future, as managers prioritize other areas of coastline.

In a talk on Monday, 19 February at the Ocean Sciences Meeting in New Orleans, John Andrew Nyman, professor of wildlife at Louisiana State University Agricultural Center, will show geological and historical evidence of creating and sustaining wetlands in the Bird’s Foot Delta over nearly two centuries. Nyman said his goal is to motivate wetland restoration managers to re-examine existing policies that exclude the Bird’s Foot Delta from major restoration programs.

“We don’t have enough money to save all the wetlands we currently have in Louisiana,” Nyman said. “Each acre is like this old pickup truck I used to drive — when is it time to give up on it?”

The dynamic Bird’s Foot Delta

Early maps of the area show three main channels in the delta, hence the name Bird’s Foot. Additional channels formed over time, creating new

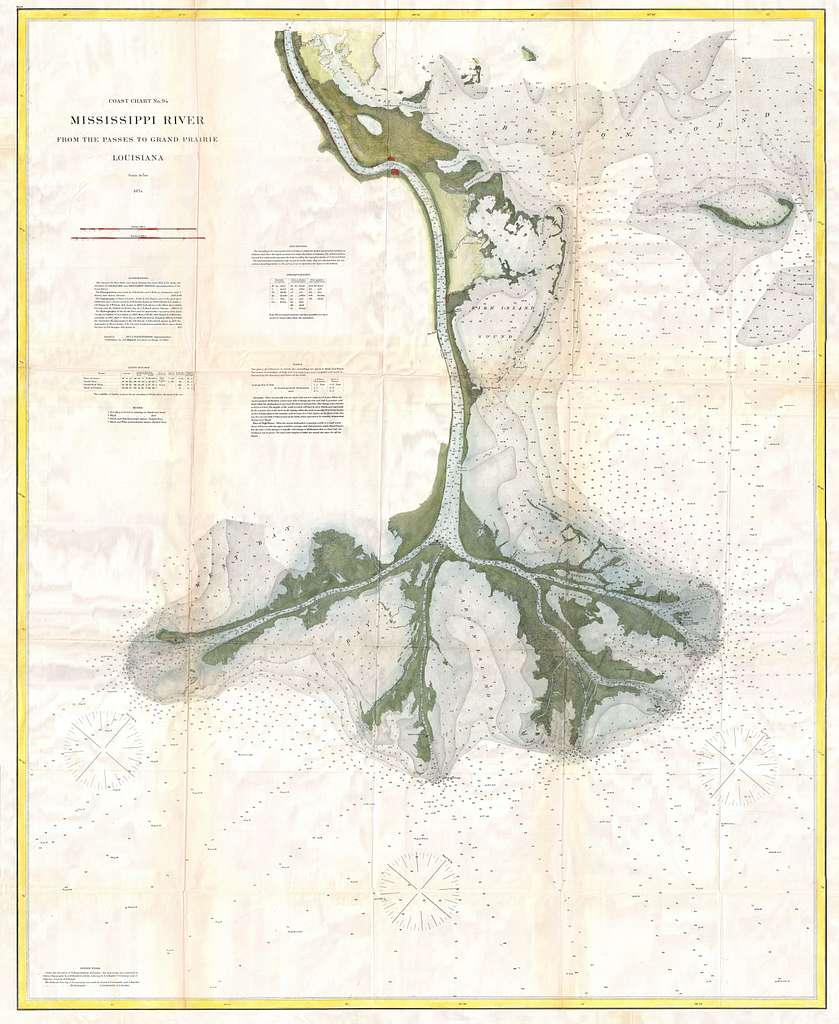

From US Coast Guard surveys, this 1874 map shows the end of the Mississippi River Delta, Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. (geographicus/public domain)

wetlands. Most of today’s wetlands in Bird’s Foot have been around since the mid-1800s, getting a significant boost during the Great Plains farming boom that led to the Dust Bowl. Farming activities supplied large volumes of sediment that were carried downriver and deposited in the delta, creating more wetland area, Nyman said.

While natural processes are the norm, there is also historical evidence that a little human effort can make a big difference in shaping wetlands. In 1862, industrious daughters of an oyster farmer named Cubit dug a ditch from the main river channel to the place where they collected oysters. They dug the new channel during the spring floods and the river soon claimed the pathway as its own. Nyman said that the ditch, called Cubit’s Gap, is now over a half mile wide and supports 48,000 acres of wetlands.

“[The delta] is very dynamic,” he added. “We have wetlands being lost, but the rivers are always building new ones.”

Sink or save?

The discovery of wetland subsidence, or sinking and compacting over time, led many to the idea that wetlands in the Bird’s Foot Delta were unnatural and unsustainable, Nyman said.

“However, there’s excellent geologic data from the 1950s showing that there are three layers of these events stacked up like pancakes,” he said. Sediment cores taken in the delta contain three peat layers, representing three cycles of deposition, stability and subsidence. “Those peat layers indicate that the wetland building of the late 1800s was a part of the cycle of natural wetland building.”

In fact, Nyman said, the Bird’s Foot Delta is the “second healthiest part of Louisiana’s extensive coastal wetlands in terms of changes in wetland acres since the 1980s.”

Nyman thinks that Bird’s Foot Delta could still be helped with restoration efforts.

“It just seems with the river currently being able to build wetlands at Bird’s Foot, this could be a very efficient use of our dollars,” he said. “I suspect that we could tweak the river to get 1, 2, or even 5% more wetlands out of it.”

###

Abstract information:

When is the Most Efficient Time to Abandon Wetlands in the Bird Foot Delta?: Relationships among navigation, wetland vegetation, and wetland-dependent fish and wildlife

Monday, 19 February, 11:35-11:45 am, Room 229-230, Second floor

Other abstracts of interest on this topic:

Introducing the Mississippi River Delta Transition Initiative (MissDelta)

Monday, 19 February, 8:45-8:55 am, Room 229-230, Second floor

A Perspective on the Complex Environmental and Economic Consequences of Mississippi Delta Backstepping

Monday, 19 February, 8:35-8:45 am, Room 229-230, Second floor

Time-varying rates of organic and inorganic mass accumulation in degrading Mississippi river deltaic marshes and relation to sea-level change

Monday, 19 February, 9:35-9:45 am, Room 229-230, Second floor

Hydrodynamics and Sediment Transport in the Retreating Mississippi River Delta

Monday, 19 February, 4:00 – 6:00 pm, Poster Hall, First floor

Sedimentary History of the Mississippi River Delta’s Pass-a-Loutre Outlet From Sediment-Core Analysis and Pb-210/Cs-137 Geochronology

Monday, 19 February, 4:00 – 6:00 pm, Poster Hall, First floor

Co-sponsored by the American Geophysical Union (AGU), the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO), and The Oceanography Society (TOS), Ocean Sciences Meeting (OSM) is the global leader in ocean sciences conferences. Every two years, the Ocean Sciences Meeting unifies the oceans community to share findings, connect scientists from around the world, and advance the impact of science. The Ocean Sciences Meeting is an Endorsed Decade Action program with the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.