5 February 2015

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The intensity of volcanic activity at deeply submerged mid-ocean ridges waxes and wanes on a roughly 100,000-year cycle, according to a new study that might help explain poorly understood variations in Earth’s climate that occur on approximately the same timetable.

Cyclical variations in Earth’s tilt and orbit–occurring at 23,000-, 41,000- and 100,000-year intervals–are known to strongly influence our planet’s long-term climate. They are associated with the coming and going of ice ages that also takes place about every 100,000 years.

In particular, changes in the roundness of Earth’s orbit around the Sun unfold on approximately the same 100,000 year cycle as the planet’s global swings between icy and temperate conditions. But, the variation in solar radiation reaching Earth due to temporarily larger and smaller distances between our planet and the Sun can’t fully explain the magnitude of the climatic shifts.

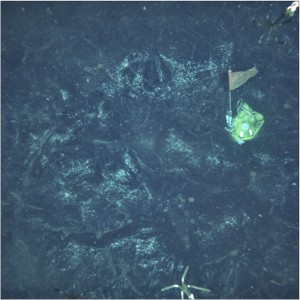

Magma from a volcanic eruption in 2006 at the East Pacific Rise, a mid-ocean ridge in the Pacific Ocean, trapped this ocean-bottom seismometer (yellow case with flag). A new study finds that the intensity of volcanic activity at deeply submerged mid-ocean ridges waxes and wanes on a roughly 100,000-year cycle.

Credit: Dan Fornari and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The new research finds evidence in the profile of sea-floor elevation that volcanic activity at mid-ocean ridges, where molten rock emerges from Earth’s interior and creates new planetary crust, coincides with these 100,000-year changes in Earth’s orbit and climate. Given that volcanic eruptions release the climate-altering gas carbon-dioxide, significant emissions of the gas might take place during upswings of undersea volcanic activity, potentially affecting the climate at 100,000-year intervals.

“Generally, mid-ocean ridges are thought of as this tiny, not very significant contributor to the carbon cycle and that is true, but that’s because they are thought of as a steady-state process. But, if they go through periods of significantly enhanced volcanism and significantly suppressed volcanism, then they may be more important than we thought,” said Maya Tolstoy, an associate professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in New York and sole author of the new study accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

Tolstoy’s study is complementary to new research published today in the journal Science that finds some glacial cycles are connected to the production of ocean crust.

Changes to the roundness of Earth’s orbit, which alter the gravitational force on the planet from the Sun, may flex the planet’s crust, intensifying volcanic activity when the already thin, undersea crust stretches out, the study explains. Changes in sea level from periodic melting and rebuilding of ice caps and glaciers could also contribute to a varying frequency of eruptions: When sea level is high, more water creates more pressure at the ocean bottom, which suppresses volcanism, and vice versa, when sea level declines again.

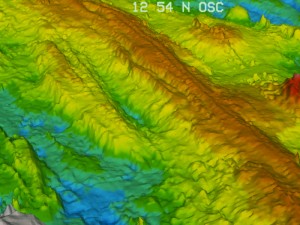

The sea floor’s texture near the East Pacific Rise, a mid-ocean ridge in the Pacific Ocean, shows alternating ridges and valleys, indicating ancient highs and lows of volcanic activity. A new study examining the depth variations, or bathymetry, of the Southern East Pacific Rise, along with information about present-day volcanic eruptions, finds that the intensity of volcanic activity at deeply submerged mid-ocean ridges waxes and wanes on a roughly 100,000-year cycle.

Credit: Haymon et al., NOAA-OE, WHOI.

In her research, Tolstoy studied 10 present-day eruptions at mid-ocean ridges and the topography around one mid-ocean ridge where ancient volcanic eruptions had left traces. Because newly formed crust pushes outward from those ridges at a regular pace as it forms, the elevation of the sea floor, representing the buildup of new rock, provides a temporal record of how much outpouring of magma took place when.

From the recent eruptions and other researchers’ seismic studies of them, Tolstoy finds that volcanic activity intensified when crust-compressing gravitational forces due to the Moon and Sun were low, underscoring that eruption rates are sensitive to forces of this type, which are also at play as the shape of Earth’s orbit gradually changes.

As for the ancient eruptions and the topographic pattern they left behind, she finds that there were fewer or smaller eruptions coinciding with periods when there was less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and when Earth’s orbit was closer to being a perfect circle. Also, there were more eruptions during periods of more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and Earth’s orbit being more out-of-round. Tolstoy’s analysis also shows a correspondence between periods of low sea level and high volcanism and the other way around.

The new findings suggest that changes in both sea level and the shape of Earth’s orbit may influence the rate of eruption at these mid-ocean ridges. These changes in seafloor volcanic activity may, in turn, feed back into climate cycles, possibly contributing to glacial cycles, the abrupt end of ice ages and the dominance of the 100,000-year climate cycle, according to the new study.

Magma from undersea eruptions congealed into these sorts of rock forms, known as striated pillow basalts, at Axial Volcano on the Juan De Fuca Ridge. A new study examining volcanic eruptions at mid-ocean ridges finds that the intensity of volcanic activity waxes and wanes on a roughly 100,000-year cycle.

Credit: Dr. Deborah Kelley, University of Washington, School of Oceanography, VISIONS’14 Cruise.

This research does not put a number on how much carbon dioxide could be released by these undersea eruptions. However, the study suggests that these volcanic eruptions could be acting as a “climatic valve” that causes the flow of greenhouse gases to fluctuate, and that models of the Earth’s climate system might be rendered more accurate by including them.

These findings could change the way scientists think about how to model Earth’s climate’s past behavior and could influence how they predict the planet’s future climate, Tolstoy said.

“We know that we can’t study these systems in isolation, that all of these different parts of our planet are linked. This study is just showing that deep-seafloor volcanism, which is sort of out of sight, out of mind, may have a long-term feedback into our whole climate system,” Tolstoy said. “If we are going to protect Earth we have to understand how the planet functions as a whole.”

Tolstoy’s research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation.

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 60,000 members in 139 countries. Join the conversation onFacebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

Notes for Journalists

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of this article by clicking on this link: 2014GL063015_tolstoy

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Nanci Bompey at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

“Mid-ocean ridge eruptions as a climate valve”

Author:

Maya Tolstoy: Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York, USA.

Contact information for the author:

Maya Tolstoy: +1 (845) 365-8791, [email protected]

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

[email protected]