15 August 2019

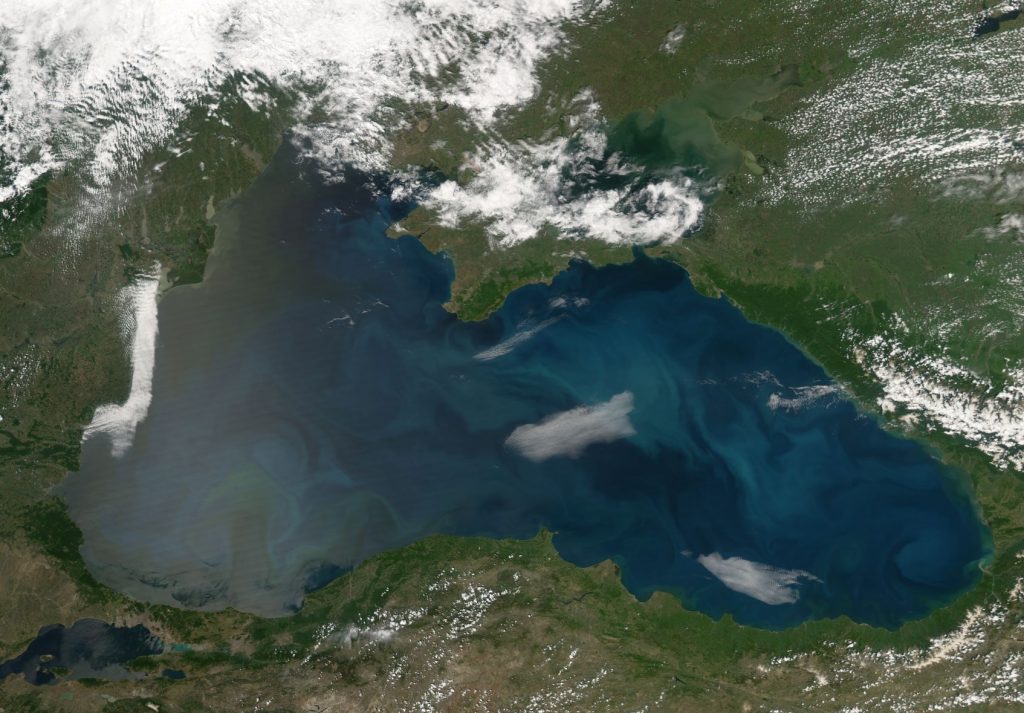

The Black Sea is bordered by six countries and receives water from many major European rivers.

Credit: NASA Earth Observatory/Jesse Allen.

AGU press contact:

Lauren Lipuma, +1 202-777-7396, [email protected]

Contact information for the researchers:

Emil Stanev, Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht Centre for Materials and Coastal Research, Germany

+49 (0)4152 87-1597 GMT+2, [email protected]

WASHINGTON—Warmer winters are starting to alter the structure of the Black Sea, which could foreshadow how ocean compositions might shift from future climate change, according to new research.

A new study published in AGU’s Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans analyzing water temperatures, density and salinity in the Black Sea from 2005 to 2019 finds warming winter weather is warming the middle water layer of the Black Sea, known as the cold intermediate layer, which exists between the oxygen-free bottom layer of the sea and the oxygenated top layer of water. This warming is causing the cold intermediate layer to mix with the other two layers of water, according to the new research.

This intermediate layer has fluctuated in the past, but in the last 14 years its core temperature has warmed 0.7 degrees Celsius (1.26 degrees Fahrenheit). The blending of the cold intermediate layer with the other layers of water could enable the water masses from the deeper layers of the sea to eventually infiltrate the top layer, which would have unknown impacts on the sea’s marine life.

The new study suggests climate change is causing the intermediate layer to warm and change, but natural fluctuations could also be playing a role, according to the study’s authors.

Studying changes in smaller water bodies like the Black Sea shows scientists how larger bodies of water might evolve in the future. The new study suggests what might happen to Earth’s oceans as the climate continues to warm, according to the researchers.

Water masses, which exist in bodies of water around the globe, influence Earth’s climate and move nutrients around the world. Changes in oceanic masses’ composition could reshape global currents, affecting the planet’s climate and ecosystems.

It is difficult to study massive water masses in the oceans so scientists use regional water masses like those in the Black Sea to determine how climate change could be affecting oceanic masses.

“We want to at least know what could happen under different global climate change scenarios,” said Emil Stanev, a physical oceanographer at Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht Center for Materials and Coastal Research in Geesthacht, Germany, and lead author of the new study.

Changing water masses

The Black Sea lies between the Balkans and Eastern Europe and receives water from many major European rivers. It also receives and loses water through the Bosporus Strait, which links the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. The Black Sea’s water stratification comes from the mixing of different water sources, creating water masses within the sea.

Water masses have distinct temperatures, salinities, and densities, usually identified by their horizontal and vertical positions in bodies of water. The Black Sea’s cold intermediate water mass’s depth varies depending on its distance from the shore. The mass separates low-saline surface water from the high-saline bottom water. Each of the sea’s water layers hosts specific organisms suited to its oceanographic conditions.

Scientists previously studied the Black Sea’s cold intermediate layer, but they had not analyzed how it has changed over time.

“They didn’t pay too much attention to the evolution of the water masses,” Stanev said.

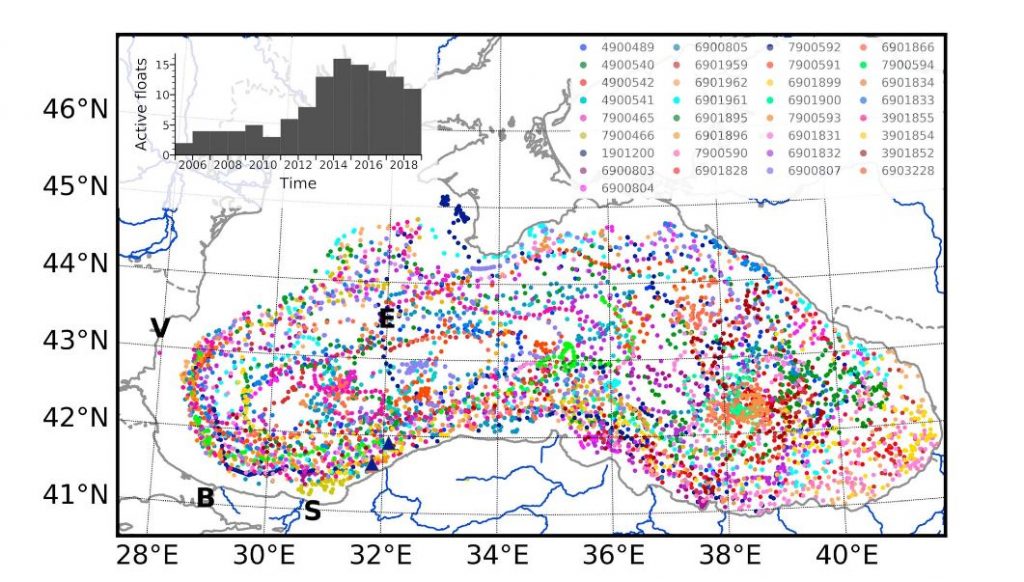

In the new study, Stanev and his colleagues charted the evolution of the Black Sea’s cold intermediate water mass for 14 years, comparing its progression with the region’s climate trends. They used battery-powered floats to measure the temperature, density and salinity from the sea surface down to 1000 meters (3281 feet) at various points throughout the seasons. They then compared the float data to surface air temperatures to see if there was a correlation between warmer winters and changes in the cold intermediate water mass’s temperature and salinity.

This graphic shows the positions of Argo floats, identified by the color in the right hand corner, that were sampling data from 2005 to 2018. The letters V, E, B, and S mark locations where a weather station collected surface data. Researchers compared those measurements with to the Black Sea’s cold intermediate layer’s warming trend.

Credit: AGU.

They found winter weather fluctuations changed the temperature and salinity of the cold intermediate layer, but the density of the water mass remained almost the same. The Black Sea’s cold intermediate layer became warmer, allowing its edges to blend with the top and bottom layers of the sea. If this trend continues, it could potentially change the stratification of the sea, according to the study’s authors. Restructuring the layers could bring sulfides, corrosive and noxious chemicals at the bottom of the sea, up to the surface, impacting marine wildlife and tourism.

Climate change might be warming the sea, but natural variability could also be responsible, according to James Murray, a chemical oceanographer at the University of Washington, who was not connected with the new study. Past research both by Murray and other scientists has shown the Black Sea’s water layers have cycled through warm and cool periods since the 1950s. However, the Black Sea’s cold intermediate layer has never been this warm, Murray added.

Both Stanev and Murray agree that more research on the evolution of the Black Sea’s layers is necessary. Continuing to study the Black Sea’s cold intermediate layer and its fluctuations will indicate whether climate change is behind the layer’s gradual disappearance.

Written by Abigail Eisenstadt, AGU public information intern.

###

Founded in 1919, AGU is a not-for-profit scientific society dedicated to advancing Earth and space science for the benefit of humanity. We support 60,000 members, who reside in 135 countries, as well as our broader community, through high-quality scholarly publications, dynamic meetings, our dedication to science policy and science communications, and our commitment to building a diverse and inclusive workforce, as well as many other innovative programs. AGU is home to the award-winning news publication Eos, the Thriving Earth Exchange, where scientists and community leaders work together to tackle local issues, and a headquarters building that represents Washington, D.C.’s first net zero energy commercial renovation. We are celebrating our Centennial in 2019. #AGU100

Notes for Journalists

This paper is freely available through September 15. Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) can download a PDF copy of the article by clicking on this link:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2019JC015076

Journalists and PIOs may also request a copy of the final paper by emailing Lauren Lipuma at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither this paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper Title

“Climate Change and Regional Ocean Water Mass Disappearance: Case of the Black Sea”

Authors

Emil V. Stanev: Institute of Coastal Research, Helmholtz‐Zentrum Geesthacht, Geesthacht, Germany;

Elisaveta Peneva: Department of Meteorology and Geophysics, Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, Sofia, Bulgaria;

Boriana Chtirkova: Department of Meteorology and Geophysics, Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, Sofia, Bulgaria.