24 February 2016

NEW ORLEANS – Millions of tiny pieces of plastic are escaping wastewater treatment plant filters and winding up in rivers where they could potentially contaminate drinking water supplies and enter the food system, according to new research being presented here.

Microplastics – tiny pieces of plastic less than 5 millimeters (0.20 inches) wide – are well known as a pollutant of concern in the oceans. However, much less is known about microplastics in freshwater ecosystems. These microplastics were found in the North Shore Channel, a drainage canal connecting Lake Michigan to the North Branch of the Chicago River, near Chicago Illinois.

Credit: Timothy Hoellein

Microplastics – small pieces of plastic less than 5 millimeters (0.20 inches) wide – are an emerging environmental concern in ocean waters, where they can harm ocean animals.

Although the majority of ocean debris – including plastics – is transported to oceans from rivers, much less is known about how microplastics are entering rivers and affecting river ecosystems, according to Timothy Hoellein, an assistant professor at Loyola University Chicago.

Rivers are sources of drinking water for many communities and also a habitat for wildlife, Hoellein said. Fish and invertebrates eat the tiny pieces of plastic in rivers, which then make their way up the food chain – possibly ending up on our dinner plates, he said. Like microplastics in the ocean, plastics found in rivers carry potentially harmful bacteria and other pollutants on their surfaces.

“Rivers have less water in them (than oceans), and we rely on that water much more intensely,” Hoellein said.

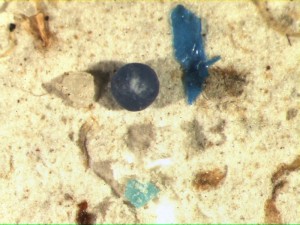

Although wastewater treatment plants are catching 90 percent or more of the incoming microplastics in wastewater, the amount of microplastics being released daily with treated wastewater into rivers is significant, ranging from 15,000 to 4.5 million microplastic particles per day per treatment plant. These microplastics can be a source of pathogenic bacteria. Pictured here is some plastic found in wastewater influent (raw sewage entering a wastewater treatment plant), near Bartlett, Illinois.

Credit: Timothy Hoellein

Hoellein previously found that water downstream from a wastewater treatment plant had a higher concentration of microplastics than water upstream from the plant. Now, new research by Hoellein and his colleagues studying 10 urban rivers in Illinois supports this initial finding. Although initial estimates suggest that wastewater treatment plants are catching 90 percent or more of the incoming microplastics, the amount of microplastics being released daily with treated wastewater into rivers is significant, ranging from 15,000 to 4.5 million microplastic particles per day per treatment plant, according to the new research.

Wastewater treatment plants were a source of microplastics in 80 percent of the rivers studied, regardless of the size of the river or the size and type of wastewater treatment plant. The new research also found that in each river, the tiny plastic particles that escaped the wastewater treatment plants were home to bacterial communities that were more likely to be potentially harmful than the bacteria found in the rivers.

“[Wastewater treatment plants] do a great job of doing what they are designed to do – which is treat waste for major pathogens and remove excess chemicals like carbon and nitrogen from the water that is released back into the river,” Hoellein said. “But they weren’t designed to filter out these tiny particles.”

Hoellein will present new findings on microplastics in rivers Thursday, February 25 at the 2016 Ocean Sciences Meeting, co-sponsored by the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography, The Oceanography Society and the American Geophysical Union.

The new research found that not only do microplastics stay in ecosystems for a long time, but they often travel a long way from their point of origin. The researchers found microplastics as far as 2 kilometers (1.24 miles) downstream from the treatment plants, which supports the idea that that rivers can transport plastic and pathogens over long distances, Hoellein said. As the microplastics travel downstream, they are being introduced and incorporated into many ecosystems, he added.

Hoellein said scientists are working to figure out how much plastic stays in the rivers and how much ends up in the oceans. Studying microplastics in rivers could help scientists better understand the entire lifecycle of these tiny pieces of plastic – from land to the ocean, Hoellein said.

“The study of microplastics shouldn’t be separated by an artificial disciplinary boundary,” he said. “These aquatic ecosystems are all connected.”

Notes for Journalists

The researchers on this study will present an oral presentation about their work on Thursday, 25 February 2016 at the Ocean Sciences Meeting. The meeting is taking place from 21 – 26 February at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center in New Orleans. Visit the Ocean Sciences Media Center for information for members of the news media.

Below is an abstract of the presentation. The abstract is a part of HI41A: The Emerging Science of Marine Debris: From Assessment to Knowledge that Informs Solutions I being held Thursday, 25 February from 8:00 a.m. to 10:00 a.m. Central Time in room RO1.

Oral presentation

Session #: HI41A

Abstract #: HI41A-02

Date: 25 February 2016

Time: 8:15 a.m.

Location: RO1

Authors:

Timothy Hoellein, John Kelly, Amanda McCormick, Amanda McCormick: Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.

Abstract:

Microplastic particles (< 5mm) in oceans are an emerging ecological concern. While rivers are considered a major source of microplastic to oceans, little is known about microplastic abundance, transport, and biological interactions in rivers. Our initial research an urban river showed microplastic collected downstream of a wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) was more abundant than upstream, more abundant than many marine sites, and had higher occurrences of bacterial taxa associated with plastic decomposition and gastrointestinal pathogens than natural habitats (e.g., seston and water column). Based on these data, we conducted follow-up projects to measure 1) the role of WWTPs on microplastic abundance in 10 rivers, 2) microplastic concentrations in WWTP influent, sludge, and effluent, and 3) deposition rates of microplastic downstream of a WWTP point source. In each project, we characterized bacterial community composition on microplastic and natural habitats using next-generation Illumina sequencing. Although maximum concentrations varied among 10 sites, microplastic concentration was significantly higher downstream of WWTPs than upstream. WWTPs retained a significant component of microplastic in two activated sludge plants (>90%). Microplastic deposition length in an urban river was >2 km, and concentrations were orders of magnitude higher in the sediment than water column. Finally, bacterial communities were distinct on microplastic in water column and sediment habitats, yet communities became more similar with increasing distance from WWTP effluent sites. These data support the role of rivers as sources of microplastic to downstream ecosystems, but also illustrate that rivers are active sites of microplastic retention and bacterial colonization. Results will inform policies and engineering advances for mitigating microplastic inputs and redistribution. We advocate for research on plastic in the environment which synthesizes data from freshwater and marine disciplines. This approach is needed to facilitate quantitative analyses of the physical and biological factors driving the ‘life cycle’ of plastic at a global scale.

Contact information for the researchers:

Timothy Hoellein, Ph.D.: [email protected], +1 (724) 272 9799

Ocean Sciences Press Office Contacts:

Nanci Bompey

+1 (914) 552-5759

[email protected]

Lauren Lipuma

+1 (504) 427-6069

[email protected]