3 February 2011

WASHINGTON—The extreme rain events that have caused flooding across northern Australia may become an increasingly familiar occurrence, new research suggests. The study uses the growth patterns in near-shore corals to determine which summers brought more rain than others, creating a centuries-long rainfall record for northern Australia.

“This reconstruction provides a new insight into rainfall in northeast Queensland,” says Janice Lough, climate scientist of the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) in Townsville, Queensland, who authored the study. “These coral samples, which date from 1639 to 1981, suggest that the summer of 1973–1974 was the wettest in 300 years. This summer is now being compared with that record-setting one.”

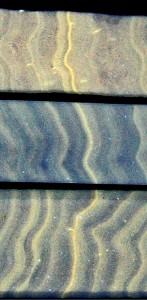

Luminescent bands from three different corals 800 kilometers apart. The most intense line is associated with extreme wet season during 1973–1974.

Photo credit: Eric Matson, AIMS

Eastern Australia is recovering from a fierce cyclone that struck last week, adding to damage from serious flooding. The flooding began in November following record rainfall, and has slowly spread to the south along the coast.

Lough’s research indicates the country might be in for more weather extremes. Following a period of relatively low precipitation and rainfall variability from the mid-18th to mid-19th centuries, average rainfall for the region has significantly increased and become more variable since the late 19th century, with wet and dry extremes becoming more frequent, she says. Her new findings have been accepted for publication in Paleoceanography, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

To create the rainfall record, Lough selected cores from her institute’s archive that had been taken from long-lived, massive Porites coral found along Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. The 17 samples had been collected from reefs located up to 30 kilometers (about 19 miles) away from Queensland’s northeastern shore.

Porites form large dome-shaped colonies that can be up to 8 meters (26 feet) in height and hundreds of years old. The coral colonies secrete underlying calcium-carbonate skeletons in annual bands of dense and less dense material. The coral bands can be counted like tree rings to calculate the colony’s age. The oldest core Lough analyzed dates back to 1639; the other coral cores analyzed for the study date back to the 17th to 19th centuries.

Northern Australian rainfall is seasonal, occurring almost exclusively during the summer. It is also highly variable year-to-year. The rain flushes degraded plant matter and a mix of compounds called humic acids into the ocean, particularly near the coast. During wet summers, more humic acid gets absorbed by the coral and stored in its skeleton. When slices of the coral are analyzed under ultraviolet light, the growth bands with more humic acid luminesce more (giving off more light) than the bands of coral growth from drier years, which allows researchers to create a record of rainfall. (The corals stimulated by ultraviolet light emit light through both fluorescence and phosphorescence; the term luminescence includes both sources of light.)

Lough used a custom-built luminometer to measure the intensity of the luminescence, which she translated into relative rainfall for each yearly band preserved in the coral. The annual records from the multiple coral cores were then calibrated against the instrumental rainfall record of the 20th century and used to reconstruct summer rainfall records back to the start of the coral colonies’ growth.

The records show that the frequency of extreme events has changed over the centuries, and is currently at a peak. During the earliest part of the reconstructed record, from about 1685 to 1784, wet years occurred on average every 12 years, and very dry years every nine. From 1785 to 1884, the frequency dropped: very wet years occurred about every 25 years, and very dry years every 14 years. However, between 1885 and 1981, the extremes increased dramatically in frequency, with very dry years taking place every 7.5 years on average, and very wet years about once every three years.

As a second part of the study, Lough compares the coral records with other proxy climate records from the paleoclimatology database of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a U.S. agency. The level of agreement between the different records was mixed, but the increase in rainfall variability since the late 19thcentury is evident in two independently-derived proxy records of a recurrent tropical climate pattern known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation.

A record of Australia’s past climate is particularly valuable, Lough says, as there is an overall lack of data on long-term climate variability in the tropics and the southern hemisphere. Such data is needed to place the current variability of the region’s climate in an historical context. The records derived from the Great Barrier Reef corals support predictions that tropical rainfall variability will increase in a warming world. AIMS researchers are currently analyzing coral cores from other tropical coral reefs of Australia to further study long-term rainfall and climate patterns.

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of this paper in press.

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Kathleen O’Neil at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release are under embargo.

“Great Barrier Reef coral luminescence reveals rainfall variability over northeastern Australia since the 17th century”

Janice Lough, Senior Principal Research Scientist, Australian Institute of Marine Science, Queensland, Australia.

Phone: 61 07 47534248, E-mail: [email protected]