The shifting of mass and consequent sea level rise due to groundwater withdrawal has caused the Earth’s rotational pole to wander nearly a meter in two decades

15 June 2023

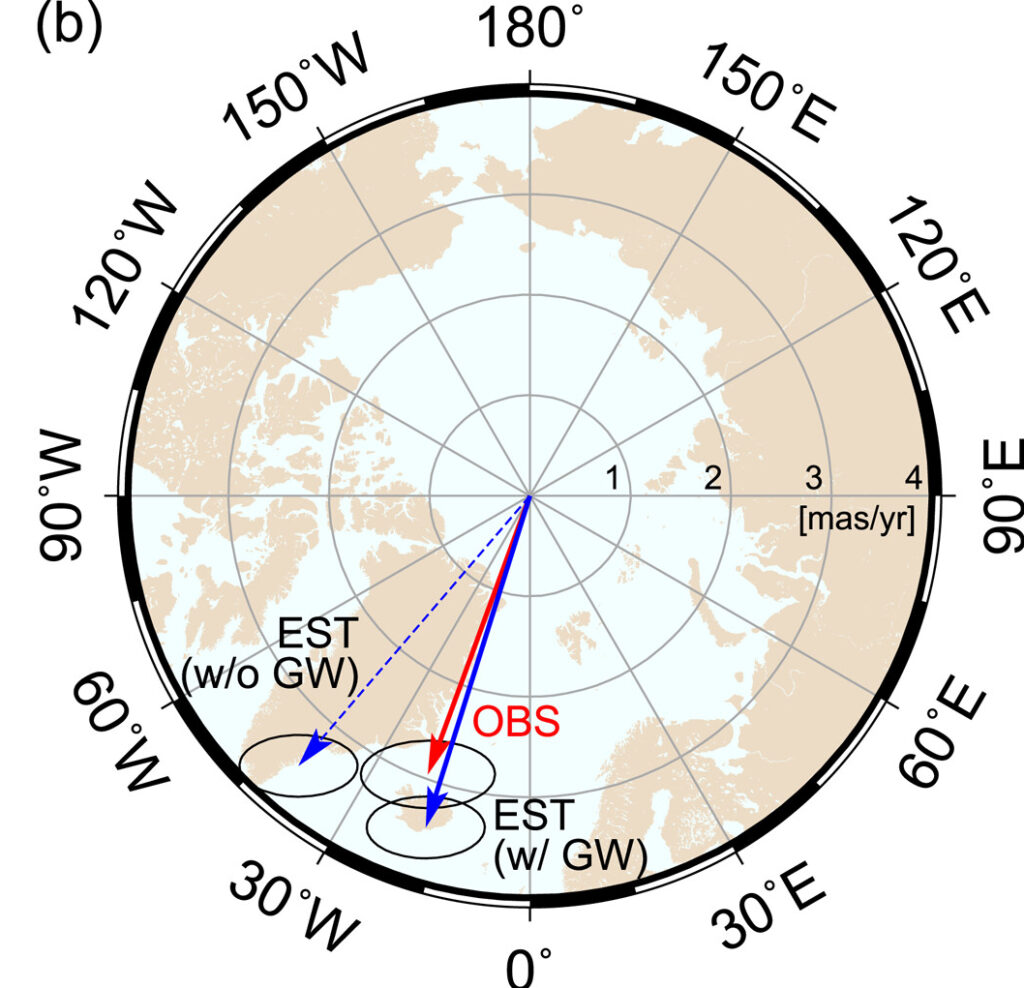

Here, the researchers compare the observed polar motion (red arrow, “OBS”) to the modeling results without (dashed blue arrow) and with (solid blue arrow) groundwater mass redistribution. The model with groundwater mass redistribution is a much better match for the observed polar motion, telling the researchers the magnitude and direction of groundwater’s influence on the Earth’s spin. Credit: Seo et al. (2023), Geophysical Research Letters

AGU press contact:

Rebecca Dzombak, [email protected] (UTC-4 hours)

Contact information for the researchers:

Ki-Weon Seo, Seoul National University, [email protected] (UTC+9 hours)

WASHINGTON — By pumping water out of the ground and moving it elsewhere, humans have shifted such a large mass of water that the Earth tilted nearly 80 centimeters (31.5 inches) east between 1993 and 2010 alone, according to a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters, AGU’s journal for short-format, high-impact research with implications spanning the Earth and space sciences.

Based on climate models, scientists previously estimated humans pumped 2,150 gigatons of groundwater, equivalent to more than 6 millimeters (0.24 inches) of sea level rise, from 1993 to 2010. But validating that estimate is difficult.

One approach lies with the Earth’s rotational pole, which is the point around which the planet rotates. It moves during a process called polar motion, which is when the position of the Earth’s rotational pole varies relative to the crust. The distribution of water on the planet affects how mass is distributed. Like adding a tiny bit of weight to a spinning top, the Earth spins a little differently as water is moved around.

“Earth’s rotational pole actually changes a lot,” said Ki-Weon Seo, a geophysicist at Seoul National University who led the study. “Our study shows that among climate-related causes, the redistribution of groundwater actually has the largest impact on the drift of the rotational pole.”

Water’s ability to change the Earth’s rotation was discovered in 2016, and until now, the specific contribution of groundwater to these rotational changes was unexplored. In the new study, researchers modeled the observed changes in the drift of Earth’s rotational pole and the movement of water — first, with only ice sheets and glaciers considered, and then adding in different scenarios of groundwater redistribution.

The model only matched the observed polar drift once the researchers included 2150 gigatons of groundwater redistribution. Without it, the model was off by 78.5 centimeters (31 inches), or 4.3 centimeters (1.7 inches) of drift per year.

“I’m very glad to find the unexplained cause of the rotation pole drift,” Seo said. “On the other hand, as a resident of Earth and a father, I’m concerned and surprised to see that pumping groundwater is another source of sea-level rise.”

“This is a nice contribution and an important documentation for sure,” said Surendra Adhikari, a research scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory who was not involved in this study. Adhikari published the 2016 paper on water redistribution impacting rotational drift. “They’ve quantified the role of groundwater pumping on polar motion, and it’s pretty significant.”

The location of the groundwater matters for how much it could change polar drift; redistributing water from the midlatitudes has a larger impact on the rotational pole. During the study period, the most water was redistributed in western North America and northwestern India, both at midlatitudes.

Countries’ attempts to slow groundwater depletion rates, especially in those sensitive regions, could theoretically alter the change in drift, but only if such conservation approaches are sustained for decades, Seo said.

The rotational pole normally changes by several meters within about a year, so changes due to groundwater pumping don’t run the risk of shifting seasons. But on geologic time scales, polar drift can have an impact on climate, Adhikari said.

The next step for this research could be looking to the past.

“Observing changes in Earth’s rotational pole is useful for understanding continent-scale water storage variations,” Seo said. “Polar motion data are available from as early as the late 19th century. So, we can potentially use those data to understand continental water storage variations during the last 100 years. Were there any hydrological regime changes resulting from the warming climate? Polar motion could hold the answer.”

###

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million advocates and professionals in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for journalists:

This study is published in Geophysical Research Letters, a fully open-access journal. View and download a pdf of the study here.

Paper title:

“Drift of the Earth’s pole confirms groundwater depletion as a significant contributor to global sea level rise 1993-2010”

Authors:

- Ki-Weon Seo (corresponding author), Center for Educational Research and Department of Earth Science Education, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- Jae-Seung Kim, Kookhyoun Youm, Department of Earth Science Education, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- Dongryeol Ryu, Department of Infrastructure Engineering, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Australia

- Jooyoung Eom, Department of Earth Science Education, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Republic of Korea

- Taewhan Jeon, Center for Educational Research, Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- Jianli Chen, Department of Land Surveying and Geo-informatics, and Research Institute for Land and Space, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong

- Clark Wilson, Department of Geological Sciences, and Center for Space Research, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA