16 July 2015

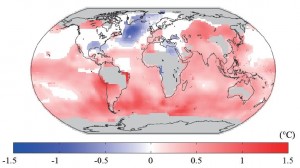

A new study found that Greenland temperatures fell from the 1970s through the early 1990s while temperatures across much of the rest of the Northern Hemisphere rose. This map shows the average difference in surface temperatures between 1920-1940 and 1975-1995. Grey areas indicate regions where not enough data was available to calculate long-term temperature changes.

Credit: Takuro Kobashi

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The sun’s activity could be affecting a key ocean circulation mechanism that plays an important role in regulating Greenland’s climate, according to a new study. The phenomenon could be partially responsible for cool temperatures the island experienced in the late 20th century and potentially lead to increased melting of the Greenland ice sheet in the coming decades, the new research suggests.

Scientists have sought to understand why Greenland cooled during the 1970s through the early 1990s while most of the Northern Hemisphere experienced rising temperatures as a result of greenhouse warming.

The new study suggests high solar activity starting in the 1950s and continuing through the 1980s played a role in slowing down ocean circulation between the South Atlantic and the North Atlantic oceans. Combined with an influx of fresh water from melting glaciers, this slow-down halted warm water and air from reaching Greenland and cooled the island while temperatures rose across the rest of the Northern Hemisphere, according to the new study accepted for publication in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

The new research also suggests weak solar activity, like the sun is currently experiencing, could slowly fire up the ocean circulation mechanism, increasing the amount of warm water and air flowing to Greenland.

Starting around 2025, temperatures in Greenland could increase more than anticipated and the island’s ice sheet could melt faster than projected, according to Takuro Kobashi, a climate scientist with the Department of Climate and Environmental Physics at the University of Bern in Switzerland and lead author of the new study.

This unexpected ice loss would compound projected sea-level rise expected to occur as a result of climate change, Kobashi said. The melting Greenland ice sheet accounted for one-third of the 3.2 millimeters (0.13 inches) rise in global sea level every year from 1992 to 2011.

“We need to really consider how solar activity will change in the future,” said Kobashi. “If solar activity becomes really low, as scientists expect, the Greenland ice sheet will melt faster than we expected from the climate model with just greenhouse gas [warming].”

The new study compared past solar activity with historical temperature records to figure out if the cooling Greenland experienced during the late 20th century was part of a long-term pattern.

The authors of a new paper placed ice from subsections of Greenland ice cores in glass flasks. Under a vacuum, the ice melted, releasing the air trapped within the ice. The scientists used the trapped air to calculate the island’s temperatures for the past 2,100 years and compare them to vacillations in solar activity.

Credit: Takuro Kobashi

The team used ice cores drilled from the Greenland ice sheet to reconstruct snow temperatures for the past 2,100 years. A relatively new technique, which measures argon and nitrogen gases trapped in the ice, allowed the scientists to measure small changes in temperature at 10- to 20-year increments.

The ice cores showed that for the past 2,000 years changes in Greenland temperatures have generally followed any temperature shifts occurring in the Northern Hemisphere. The new research found that the change in Greenland temperatures vacillated up and down around the average change in Northern Hemisphere temperatures over time. The vacillations coincided with changes in the sun’s energy output that occurred over multiple decades, according to the new study.

When the sun’s energy output increased, there was a bigger drop in Greenland’s temperature compared to the change in average temperature across the Northern Hemisphere. When the sun’s energy output decreased, there was a larger increase in Greenland’s temperature compared to the change in average temperature that occurred across the Northern Hemisphere.

Climate models showed that changes in solar activity could prompt shifts in ocean and air circulation in the North Atlantic that affect Greenland’s climate, according to the new study.

Shifting circulation patterns

Water circulation in the Atlantic follows a steady pattern of movement, called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). Warm water flows from the South Atlantic toward the North Atlantic, transferring heat toward Greenland. As the water cools, it sinks to the ocean floor and travels south toward the tropics, completing the circular pattern.

During a period of high solar activity, more energy from the sun reaches Earth and is transferred to tropical waters. When this warmer-than-usual water reaches the North Atlantic, it is not dense enough to sink. With nowhere to go, the water causes a traffic jam and the water circulation pattern slows down.

Changes in solar activity can also alter the atmospheric circulation pattern over the Atlantic, which in turn affects ocean circulation, but how this process works is still unknown, said Kobashi.

In the late 20th century, there also was a compounding problem. Large amounts of freshwater gushed into the North Atlantic as climate change caused increased melting of glaciers, icebergs, and the Greenland ice sheet. Freshwater, being more buoyant than salt water, entered the intersection where cool water drops to the ocean floor and travels south to the tropics. Climate models showed that the water in the intersection became less salty and less likely to sink. Models also showed that additional freshwater came from an increase in rainfall, according to the new study.

The traffic jam worsened and the water circulation pattern that transfers heat from the South Atlantic to the North Atlantic slowed. This slow-down caused the air above Greenland to cool and temperatures there to drop, according to the new study.

Because the oceans take a long time to heat up or cool down, the temperature changes in Greenland lagged 10 to 40 years behind the high solar activity, showing up from the 1970s through the early 1990s, according to the new study.

The new study suggests low solar activity could have the opposite effect and lead to warmer temperatures in Greenland in another decade. When there is less solar energy reaching the Earth, water reaching Greenland easily sinks and returns to the tropics along the ocean floor. The water circulation pattern speeds up, quickly funneling heat toward Greenland and warming the island.

Greenhouse gases versus solar activity

The new study makes a good case that the solar maximum in the 1950s through the 1980s may have played a role in the cooling Greenland saw in the late 20th century, said Michael Mann, a climate scientist with the Department of Meteorology at Penn State University in University Park, Pennsylvania, who was not involved in the new study.

Another recent study by Mann and his colleagues proposed that trapped greenhouse gases from fossil fuel burning caused warming across the Northern Hemisphere and triggered an increase in ice melt. This led to the slowdown in ocean circulation and a cooler Greenland.

Both studies suggest buoyant meltwater from melting glaciers would have interrupted the sinking of the AMOC and its return to the tropics along the bottom of the ocean. But the new research suggests solar activity is the main driver behind the changes to the ocean circulation pattern.

“I’m open-minded that the real answer is more complicated, and it may be a combination of the two hypotheses,” said Mann. “This article paves the way for a more in-depth look at what is going on. The challenge now will be teasing apart the two effects and trying to assess the relative importance of both of them.”

Kobashi contends that solar activity explains the change in ocean circulation and Greenland warming since 1995, which he says cannot be explained by increasing greenhouse gases alone.

###

The American Geophysical Union is dedicated to advancing the Earth and space sciences for the benefit of humanity through its scholarly publications, conferences, and outreach programs. AGU is a not-for-profit, professional, scientific organization representing more than 60,000 members in 139 countries. Join the conversation on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and our other social media channels.

Notes for Journalists

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of the article by clicking on this link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2015GL064764/full?campaign=wlytk-41855.5282060185

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Leigh Cooper at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the papers nor this press release is under embargo.

“Modern solar maximum forced late 20th century Greenland cooling”

Authors:

T. Kobashi: Climate and Environmental Physics, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; and Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland; and National Institute of Polar Research, Tokyo, Japan;

J.E. Box: Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Copenhagen, Denmark;

B.M. Vinther: Center for Ice and Climate, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark;

K. Goto-Azuma: National Institute of Polar Research, Tokyo, Japan; and Department of Polar Science, Graduate University for Advanced Studies, Tokyo, Japan;

T. Blunier: Center for Ice and Climate, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark;

J.W.C. White: Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA;

T. Nakaegawa: Meteorological Research Institute, Tsukuba, Japan;

C.S. Andresen: Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Contact Information for the Authors:

Takuro Kobashi: 011-41-03-1631-8601, [email protected]

Leigh Cooper

+1 (202) 777-7324

[email protected]