16 January 2014

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Ocean researchers working on the coral reefs of Palau in 2011 and 2012 made two unexpected discoveries that could provide insight into corals’ resistance and resilience to ocean acidification, and aid in the creation of a plan to protect them.

The team collected water samples at nine points along a transect that stretched from the open ocean, across the barrier reef, into the lagoon, and then into the bays and inlets around the Rock Islands of Palau in the western Pacific Ocean. With each location they found that the seawater became increasingly acidic as they moved toward land.

“When we first plotted up those data, we were shocked,” said lead author Kathryn Shamberger, then a postdoctoral scholar at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and a chemical oceanographer. “We had no idea the level of acidification we would find. We’re looking at reefs today that have acidification levels that we expect for the open ocean in that region by 2100.”

Despite living in waters that are more acidic than average seawater, the corals living in the bays around Palau’s Rock Islands are unexpectedly diverse and healthy.

Credit: Palau International Coral Reef Center

Shamberger conducted the fieldwork in Palau with other researchers from the laboratory of WHOI biogeochemist Anne Cohen as well as scientists from the Palau International Coral Reef Center (PICRC).

While ocean chemistry varies naturally at different locations, it is changing around the world due to increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The ocean absorbs the carbon dioxide, which reacts with seawater, lowering its overall pH and making it more acidic. This process also removes carbonate ions needed by corals and other organisms to build their skeletons and shells. Corals growing in low pH conditions, both in laboratory experiments to simulate future conditions and in other naturally low pH ocean environments, show a range of negative impacts including juveniles having difficulty constructing skeleton, fewer varieties of corals, less coral cover, more algae growth, and more porous corals with greater signs of erosion from other organisms.

The new research, published today in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union, explains the natural biological and geomorphological causes of the more acidic water near Palau’s Rock Islands and describes a surprising second finding – that the corals living in that more acidic water were unexpectedly diverse and healthy. The unusual finding, which is contrary to what has been observed in other naturally low pH coral reef systems, has important implications for the conservation of corals in all parts of the world.

“When you move from a high pH reef to a low pH neighboring reef, there are big changes, and they are negative changes,” said Cohen, a co-author on the paper and leader of the project. “However, in Palau where the water is most acidic, we see the opposite. We see a coral community that is more diverse, hosts more species, and has greater coral cover than in the non-acidic sites. Palau is the exception to the places scientists have studied.”

Ocean acidification

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution biogeochemist Anne Cohen, pictured here, and her research group are developing new tools to quantify coral community resistance and resilience to the threat posed by the warming and acidification of the oceans. Cohen is co-author of a paper published this week that found coral reefs in Palau are surprisingly resistant to naturally acidified waters.

Credit: Ari Shapiro, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Through analysis of the water chemistry in Palau, the scientists found the acidification is primarily caused by the shell building done by the organisms living in the water – removing carbonate ions from seawater to construct their shells and skeletons, called calcification. A second reason is the organisms’ respiration, which adds carbon dioxide to the water when they breathe.

“These things are all happening at every reef,” said Cohen. “What’s really critical here is the residence time of the sea water.”

“In the Rock Islands, the water sits in the bays for a long time. This is a big area that’s like a maze with lots of channels and inlets for the water to wind around,” explained Shamberger. “Calcification and respiration are continually happening at these sites while the water sits there, and it allows the water to become more and more acidic. It’s a little bit like being stuck in a room with a limited amount of oxygen – the longer you’re in there without opening a window, you’re using up oxygen and increasing carbon dioxide.”

Ordinarily, without fresh air coming in, it gets harder and harder for living things to thrive. “Yet in the case of the corals in Palau,” she said, “we’re finding the opposite.”

“What we found is that coral cover and coral diversity actually increase as you move from the outer reefs and into the Rock Islands, which is exactly the opposite of what we were expecting,” Shamberger added.

Genetics or environment

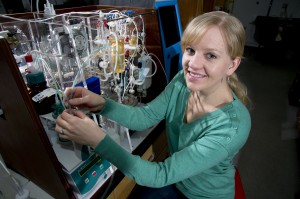

Chemical oceanographer Katie Shamberger, shown here with an instrument that measures seawater carbon dioxide parameters, led the water sampling effort in Palau in the western Pacific Ocean. The scientists found that the water in the Rock Islands was at levels of acidification that are expected for the open ocean in the tropical western Pacific Ocean by the end of the century.

Credit: Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

The scientists’ next steps are to determine if these corals are genetically adapted to low pH or whether Palau provides a “perfect storm” of environmental conditions that allows these corals to survive the low pH. “If it’s the latter, it means if you took those corals out of that specific environment and put them in another low pH environment that doesn’t have the same combination of conditions, they wouldn’t be able to survive,” said Cohen. “But if they’re genetically adapted to low pH, you could put them anywhere and they could survive.”

“These reef communities have developed under these conditions for thousands of years,” said Shamberger, “and we’re talking about conditions that are going to be occurring in a lot of the rest of the ocean by the end of the century. We don’t know if other coral reefs will be able to adapt to ocean acidification – the time scale might be too short.”

The scientists are careful to stress that their finding in Palau is different from every other low pH environment that has been studied. “When we find a reef like Palau, where the coral communities are thriving under low pH, that’s an exception,” said Cohen. “It doesn’t mean coral reefs around the globe are going to be OK under ocean acidification conditions. It does mean that there are some coral communities out there – and we’ve found one – that appear to have figured it out. But that doesn’t mean all coral reef ecosystems are going to figure it out.”

The Rock Islands of Palau are like a maze with lots of channels and inlets for the water to wind around. The water sits in the bays for a long time before being flushed out, becoming more and more acidic. Organisms living in the water are changing the water’s chemistry as they build their shells and breathe carbon dioxide into the water.

Credit: Pat Lohmann, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

By working with scientists at the Palau International Coral Reef Center (PICRC), the government of the Republic of Palau, and The Nature Conservancy, the researchers aim to assist in the development of indices of reef vulnerability to ocean acidification that can be directly incorporated into the selection and design of marine protected area networks.

“In Palau, we have these special and unique places where organisms have figured out how to survive in an acidified environment. Yet, these places are much more prone to local human impacts because of their closeness to land and because of low circulation in these areas,” said co-author Yimnang Golbuu, CEO of the PICRC. “We need to put special efforts into protecting these places and to ensure that we can incorporate them into the Protected Areas Network in Palau.”

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation, the WHOI Ocean Life Institute, and The Nature Conservancy.

*****

Notes for Journalists

Journalists and public information officers (PIOs) of educational and scientific institutions who have registered with AGU can download a PDF copy of this article by clicking on this link: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2013GL058489/abstract

Or, you may order a copy of the final paper by emailing your request to Nanci Bompey at [email protected]. Please provide your name, the name of your publication, and your phone number.

Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo

“Diverse Coral Communities in Naturally Acidified Waters of a Western Pacific Reef”

Authors:

Kathryn E. F. Shamberger, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA;

Anne Cohen, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA;

Yimnang Goldbuu, Palau International Coral Reef Center, Koror, Palau;

Daniel C. McCorkle, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA;

Steven J. Lentz, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA;

Hannah C. Barkley, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA, USA.

Contact information for the authors:

Kathryn E. F. Shamberger, +1 (508) 289-2722, [email protected].

Nanci Bompey

+1 (202) 777-7524

[email protected]

WHOI Contact:

WHOI Media Relations Office

+1 (508) 289-3340

[email protected]