The massive storm near the gas giant’s equator has been shrinking, but collisions with a series of anticyclones are likely only surface deep

17 March 2021

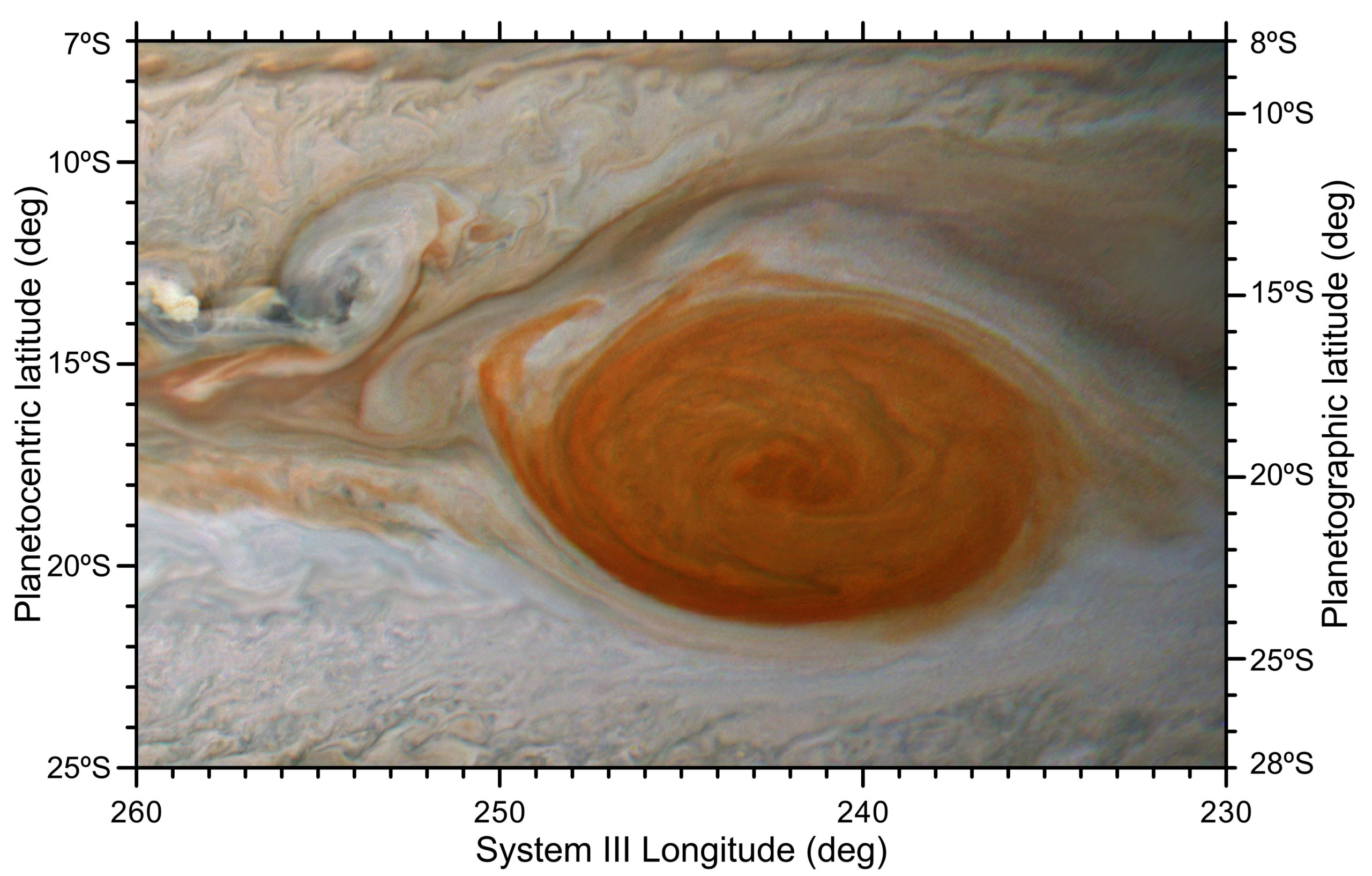

A flake of red peels away from Jupiter’s Great Red Spot during an encounter with a smaller anticyclone, as seen by the Juno spacecraft’s high resolution JunoCam on 12 February 2019. Although the collisions appear violent, planetary scientists believe they are mostly surface effects, like the crust on a crème brûlée.

Credit: AGU/Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets

AGU press contact:

Liza Lester, +1 (202) 777-7494, [email protected] (UTC -5:00 hours)

Contact information for the researchers:

Agustín Sánchez-Lavega, Escuela de Ingeniería de Bilbao, Universidad del País Vasco

(Basque Country University in Bilbao, Spain),

[email protected] (UTC +1:00 hour)

WASHINGTON— The stormy, centuries-old maelstrom of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot was shaken but not destroyed by a series of anticyclones that crashed into it over the past few years.

The smaller storms cause chunks of red clouds to flake off, shrinking the larger storm in the process. But the new study found that these disruptions are “superficial.” They are visible to us, but they are only skin deep on the Red Spot, not affecting its full depth.

The new study was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, AGU’s journal for research on the formation and evolution of the planets, moons and objects of our solar system and beyond.

“The intense vorticity of the [Great Red Spot], together with its larger size and depth compared to the interacting vortices, guarantees its long lifetime,” said Agustín Sánchez-Lavega, a professor of applied physics at the Basque Country University in Bilbao, Spain, and lead author of the new paper. As the larger storm absorbs these smaller storms, it “gains energy at the expense of their rotation energy.”

The Red Spot has been shrinking for at least the past 150 years, dropping from a length of about 40,000 kilometers (24,850 miles) in 1879 to about 15,000 kilometers (9,320 miles) today, and researchers still aren’t sure about the causes of the decrease, or indeed how the spot was formed in the first place. The new findings show the small anticyclones may be helping to maintain the Great Red Spot.

Timothy Dowling, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Louisville who is a planetary atmospheric dynamics expert not involved in the new study, said that “it’s an exciting time for the Red Spot.”

Stormy collisions

Before 2019, the larger storm was only hit by a couple of anticyclones a year while more recently it was hit by as many as two dozen a year. “It’s really getting buffeted. It was causing a lot of alarm,” Dowling said.

Sánchez-Lavega and his colleagues were curious to see whether these relatively smaller storms had disturbed their big brother’s spin.

The iconic feature of the gas giant sits near its equator, dwarfing earthly concepts of a big bad storm for at least 150 years since its first confirmed observation, though observations in 1665 may have been from the same storm. The Great Red Spot is about twice the diameter of Earth and blows at speeds of up to 540 kilometers (335 miles) per hour along its periphery.

“The [Great Red Spot] is the archetype among the vortices in planetary atmospheres,” said Sánchez-Lavega, adding that the storm is one of his “favorite features in planetary atmospheres.”

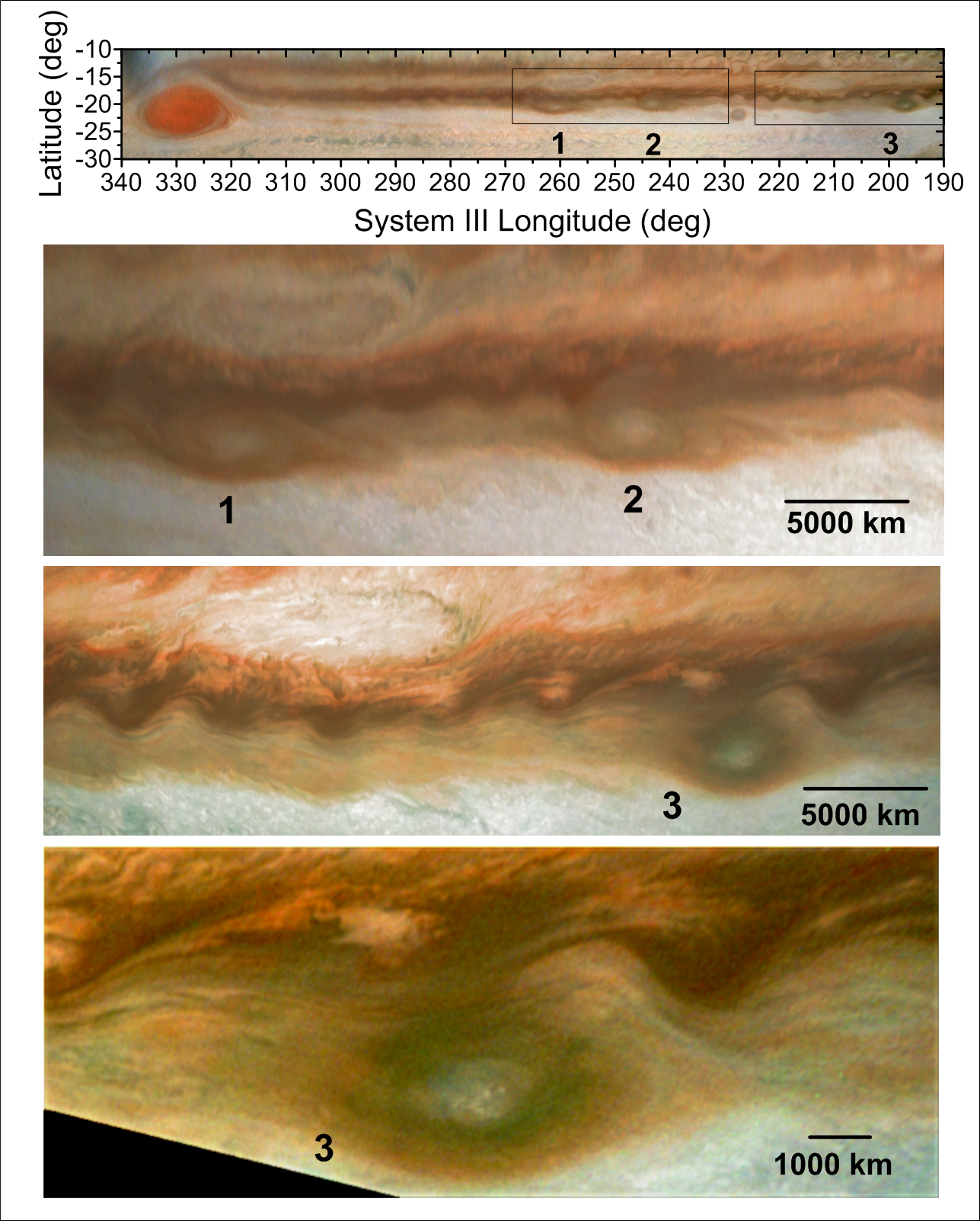

A series of smaller (but still enormous) anticyclones approached the Jupiter’s iconic red storm in 2019. The top image shows smaller anticyclones numbered 1, 2, and 3, moving towards the Great Red Spot. The three other images show enlargements of the anticyclones.

Credit: AGU/Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets

Cyclones like hurricanes or typhoons usually spin around a center with low atmospheric pressure, rotating counter-clockwise in the northern hemisphere and clockwise in the southern, whether on Jupiter or Earth. Anticyclones spin the opposite way as cyclones, around a center with high atmospheric pressure. The Great Red Spot is itself an anticyclone, though it is six to seven times as big as the smaller anticyclones that have been colliding with it. But even these smaller storms on Jupiter are about half the size of the Earth, and about 10 times the size of the largest terrestrial hurricanes.

Sánchez-Lavega and his colleagues looked at satellite images of the Great Red Spot for the past three years taken from the Hubble Space Telescope, the Juno spacecraft in orbit around Jupiter and other photos taken by a network of amateur astronomers with telescopes.

Devourer of storms

The team found the smaller anticyclones pass through the high-speed peripheral ring of the Great Red Spot before circling around the red oval. The smaller storms create some chaos in an already dynamic situation, temporarily changing the Red Spot’s 90-day oscillation in longitude, and “tearing the red clouds from the main oval and forming streamers,” Sánchez-Lavega said.

“This group has done an extremely careful, very thorough job,” Dowling said, adding that the flaking of red material we see is akin to a crème brûlée effect, with a swirl apparent for a few kilometers on the surface that doesn’t have much impact on the 200-kilometer (125-mile) depth of the Great Red Spot.

The researchers still don’t know what has caused the Red Spot to shrink over the decades. But these anticyclones may be maintaining the giant storm for now.

“The ingestion of [anticyclones] is not necessarily destructive; it can increase the GRS rotation speed, and perhaps over a longer period, maintain it in a steady state,” Sánchez-Lavega said.

###

AGU (www.agu.org) supports 130,000 enthusiasts to experts worldwide in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, we advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Notes for Journalists

This research study will be free available for 30 days. Download a PDF copy of the paper here. Neither the paper nor this press release is under embargo.

Paper title:

“Jupiter’s Great Red Spot: strong interactions with incoming anticyclones in 2019”

Authors:

- Agustín Sánchez-Lavega, corresponding author, (Universidad del País Vasco UPV/EHU)

- Asier Anguiano-Arteaga (Universidad del Pais Vasco UPV/EHU)

- Peio Iñurrigarro (Universidad del Pais Vasco UPV/EHU)

- Enrique Garcia-Melendo (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya UPC)

- Jon Legarreta (Universidad del País Vasco)

- Ricardo Hueso (UPV/EHU)

- Jose Francisco Sanz-Requena (Universidad Europea Miguel de Cervantes)

- Santiago Perez-Hoyos (Universidad del Pais Vasco UPV/EHU)

- Iñigo Mendikoa (Universidad del Pais Vasco UPV/EHU)

- Manel Soria (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya UPC)

- Jose Rojas (Universidad del Pais Vasco UPV/EHU)

- Marc Andrés-Carcasona (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya UPC)

- Arnau Prat-Gasull (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya UPC)

- Iñaki Ordoñez-Etxebarria (Universidad del País Vasco UPV/EHU)

- John Rogers (British Astronomical Association)

- Clyde Foster (Astronomical Society of Southern Africa)

- Shinji Mizumoto (Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers ALPO-Japan)

- Andy Casely (Independent scholar)

- Candice Hansen (Planetary Science Institute)

- Glenn Orton (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology)

- Thomas Momary (Jet Propulsion Laboratory)

- Gerald Eichstädt (Independent scholar)