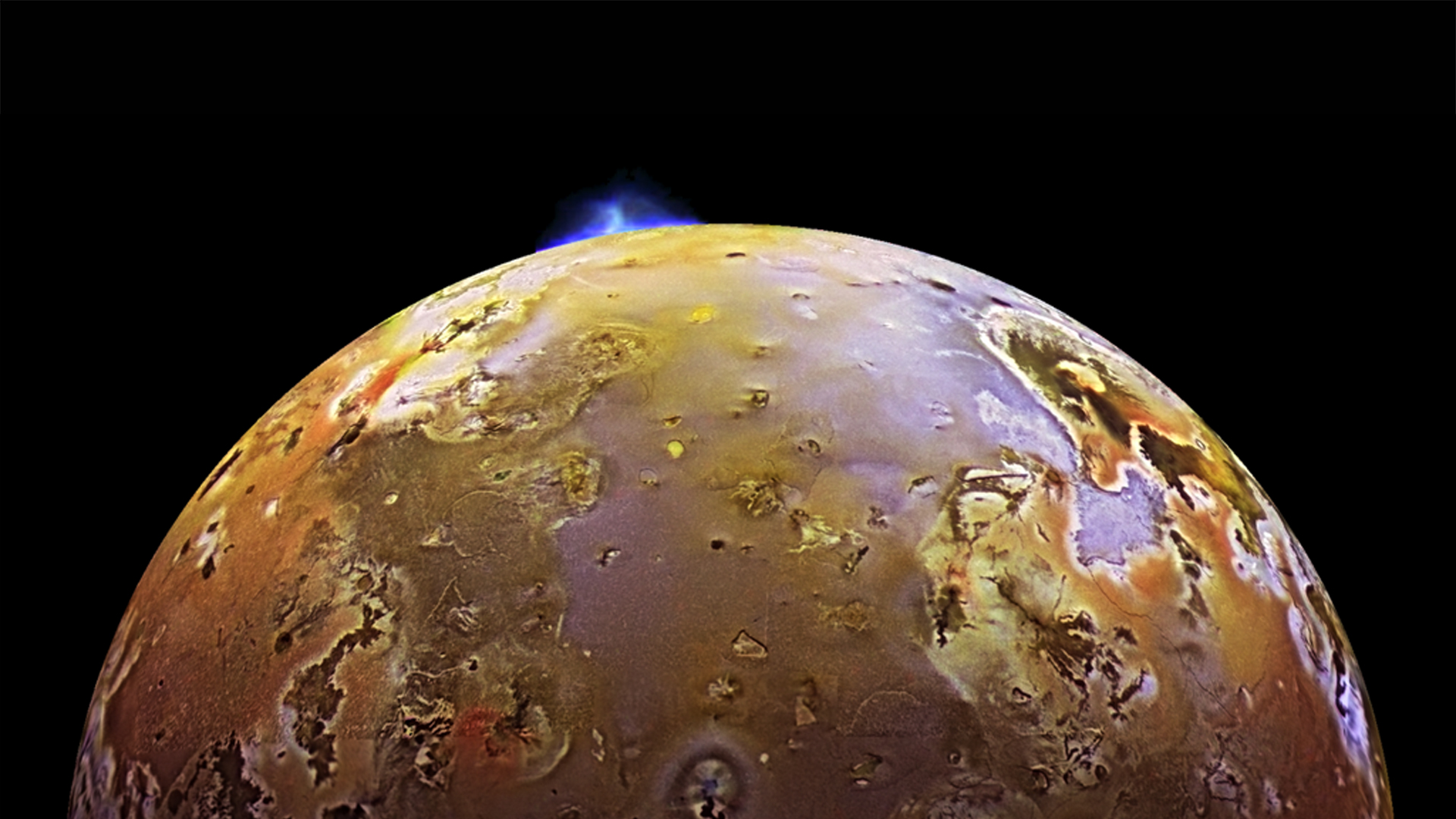

A volcano erupts on Io, our solar system’s most volcanically active world, in an image captured in 1997 by the Galileo spacecraft. In late 2024, the Juno spacecraft witnessed Io’s most powerful known eruption, revealing clues about its subsurface structure. Credit: NASA, NASA-JPL, DLR

AGU News

Press registration is open for the 2026 Ocean Sciences Meeting in Glasgow, Scotland

Staff, freelance and student journalists, press officers and institutional writers are eligible to apply for complimentary press registration for the conference, which will convene 22-27 February. [media advisory][OSM26 Press][eligibility guidelines][preview conference hotels]

Featured Research

Io’s largest known eruption hints at a sponge-like interior

In late December of 2024, NASA’s Juno spacecraft witnessed the most intense eruption ever recorded on Io, Jupiter’s most volcanically active moon. The eruption spanned 65,000 square kilometers (over 25,000 square miles) of the southern hemisphere and released 140 to 260 terawatts of energy, over 1,000 times more than usual for the area by previous estimates. Three other hotspots also lit up enough to place them among the 10 most powerful known on Io — though other nearby volcanoes did not. Scientists interpret this as a single event affecting an underground network of massive, interconnected magma chambers, almost like pores in a giant sponge. [JGR Planets study]

Earthquakes may tease their final sizes right at the start

Just a few seconds of an earthquake’s onset hold enough information to predict its eventual size, potentially. After training a deep learning model on data from over 2,100 earthquakes showing changes in the energy they released over time, researchers found the model needed, at most, the first five seconds of data from a quake — accounting for the first 20% of the rupture process — to predict its magnitude with at least 80% accuracy. The finding could eventually inform the creation of more effective earthquake early warning systems. [JGR Machine Learning and Computation study]

To save water in the southwestern U.S., attitude change efforts alone may not suffice

Rather than rely solely on policies encouraging residents to save water, cities and towns in the southwestern U.S. should employ a diverse set of strategies to conserve water as human-driven climate change makes droughts more frequent and intense, a recent study suggests. Researchers used a computer model to simulate how policies aimed at reducing water demand affected reservoir supply in Denver, Las Vegas, and Phoenix under different climate change scenarios. While the policies counteracted the negative impacts of climate change in some cases, they proved insufficient in others. To maintain water availability under climate change, the team wrote, a multi-pronged approach may be the safest bet. [Water Resources Research study]

US faces coin-toss odds of trillion-dollar climate damages in the next five years

The U.S. has a roughly 54% chance of suffering over one trillion dollars in damages from extreme weather and climate disasters between 2026 and 2030 alone. The estimate comes from a recent statistical model using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s database of billion-dollar climate disasters from 1980 to 2024 to extrapolate into the near future. Disasters at that level are occurring more often due to both climate change and communities’ increasing vulnerability: in the 1980 to 2024 period, even the record-high financial toll of Hurricane Katrina was not an outlier but an expected result. [Geophysical Research Letters study]

Beaufort Sea landfast ice, once thought consistent, is disappearing

An updated 27-year record of northern Alaska’s landfast sea ice — ice reaching over the sea from the coast — contradicts previous findings that the Beaufort Sea’s seasonal landfast ice has held steady since the 1970s. Instead, a comparison of the new data against 1970s satellite data shows its annual extent shrank an average of 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) from then to the late 1990s and aughts. The ice’s seasonal duration has also shortened at a rate of 13 days per decade from 1996 to 2023, an outcome consistent with ocean warming. The researchers say the Beaufort Sea is likely on track to lose its most extensive areas of landfast sea ice, which provide seasonal coastal erosion protection, wildlife habitat, and platforms for human hunting and travel. [JGR Oceans study]